The Sound of Waves (6 page)

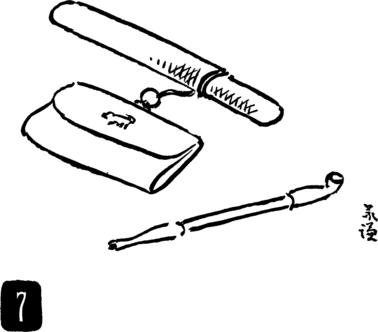

The lighthouse-keeper spent the greater part of each day beside the sunken hearth, smoking cheap New Life cigarettes, economically cutting them into short lengths and fitting them into a long, slender brass pipe. The lighthouse was dead during the daytime, with only one of the young assistants in the watchhouse to report ship movements.

Toward evening that day, even though no etiquette lesson was scheduled, Hatsue came visiting, bringing a door-gift of some sea-cucumbers wrapped in newspaper. Beneath her blue-serge skirt she was wearing long flesh-colored stockings, and over them red socks. Her sweater was her usual scarlet one.

Hatsue had no sooner entered the house than the mistress began giving advice, not mincing her words:

“When you wear a blue skirt, Hatsue-san, you ought to wear black hose. I know you have some because you were wearing them only the other day.”

“Well …” Blushing slightly, Hatsue sat down beside the hearth.

At the regular lessons of etiquette and home-making the girls sat listening fairly intently and the mistress spoke in a lecturing tone of voice, but now, seated by the hearth with Hatsue, she began talking in a free and easy way. As her visitor was a young girl, she talked first in a general sort of way about love, and finally got around to asking such direct questions as “Isn’t there someone you like very much?” At times, when the lighthouse-keeper saw the girl become rattled, he would ask a teasing question of his own.

When it began to grow late they asked Hatsue several times if she didn’t have to get home for supper and if her father wouldn’t be waiting for her. It was Hatsue who finally made the suggestion that she help prepare their supper.

Until now Hatsue had simply sat there blushing furiously and looking down at the floor, not so much as touching the refreshments put before her. But, once in the kitchen, she quickly recovered her good spirits. Then, while slicing the sea-cucumbers, she began singing the traditional Ise chorus used on the island for accompanying the Lantern Festival dancing; she had learned it from her aunt the day before:

Tall chests, long chests, traveling chests—

Since your dower is so great, my daughter

,

You must never think of coming back

.

But oh, my mother, you ask too much:

When the east is cloudy, they say the wind will blow;

When the west is cloudy, they say the rain will fall;

And when a fair wind changes—

Yoi! Sora!—

Even the largest ship returns to port

.

“Oh, have you already learned that song, Hatsue-san?” the mistress said. “Here it’s already three years since we came here and I don’t know it all even yet.”

“Well, but it’s almost the same as the one we sang at Oizaki,” Hatsue answered.

Just then there was the sound of footsteps outside, and from the darkness someone called:

“Good evening.”

“That must be Shinji-san,” the mistress said, sticking her head out the kitchen door. Then:

“Well, well! More nice fish. Thanks.… Father, Kubo-san’s brought us more fish.”

“Thanks again, thanks again,” the lighthouse-keeper called from the hearth. “Come on in, Shinji boy, come on in.”

During this confusion of welcome and thanks Shinji and Hatsue exchanged glances. Shinji smiled. Hatsue smiled too. But the mistress happened to turn around suddenly and intercept their smiles.

“Oh, you two already know each other, do you? H’m, it’s a small place, this village. But that makes it all the better, so do come on in, Shinji-san—Oh, and by the way, we had a letter from Chiyoko in Tokyo. She particularly asked about Shinji-san. I don’t guess there’s much doubt about who Chiyoko likes, is there? She’ll be coming

home soon for spring vacation, so be sure and come to see her.”

Shinji had been just on the point of coming into the house for a minute, but these words seemed to wrench his nose. Hatsue turned back to the sink and did not look around again. The boy retreated back into the dusk. They called him several times, but he would not come back. He made his bow from a distance and then took to his heels.

“That Shinji-san—he’s really the bashful one, isn’t he, Father?” the mistress said, laughing.

The lone sound of her laughter echoed through the house. Neither the lighthouse-keeper nor Hatsue even smiled.

Shinji waited for Hatsue where the path curved around Woman’s Slope.

At that point the dusk surrounding the lighthouse gave way to the last faint light that still remained of the sunset. Even though the shadows of the pine trees had become doubly dark, the sea below them was brimming with a last afterglow. All through the day the first easterly winds of spring had been blowing in off the sea, and even now that night was falling the wind did not feel cold on the skin.

As Shinji rounded Woman’s Slope even that small wind died away, and there was nothing left in the dusk but calm shafts of radiance pouring down between the clouds.

Looking down, he saw the small promontory that jutted out into the sea to form the far side of Uta-jima’s harbor. From time to time its tip was shrugging its rocky shoulders swaggeringly, rending asunder the foaming waves. The vicinity of the promontory was especially

bright. Standing on the promontory’s peak there was a lone red-pine, its trunk bathed in the afterglow and vividly clear to the boy’s keen eyes. Suddenly the trunk lost the last beam of light. The clouds overhead turned black and the stars began to glitter above Mt. Higashi.

Shinji laid his ear against a jutting rock and heard the sound of short, quick footsteps approaching along the flagstone path that led down from the stone steps at the entrance to the lighthouse residence. He was planning to hide here as a joke and give Hatsue a scare when she came by. But as those sweet-sounding footsteps came closer and closer he became shy about frightening the girl. Instead, he deliberately let her know where he was by whistling a few lines from the Ise chorus she had been singing earlier:

When the east is cloudy, they say the wind will blow;

When the west is cloudy, they say the rain will fall;

And even the largest ship …

Hatsue rounded Woman’s Slope, but her footsteps never paused. She walked right on past as though she had no idea Shinji was there.

“Hey! Hey!”

But still the girl did not look back. There was nothing to do but for him to walk silently along after her.

Entering the pine grove, the path became dark and steep. The girl was lighting her way with a small flashlight. Her steps became slower and, before she was aware of it, Shinji had taken the lead.

Suddenly the girl gave a little scream. The beam of the flashlight soared like a startled bird from the base of the pine trees up into the treetops.

The boy whirled around. Then he put his arms around

the girl, lying sprawled on the ground, and pulled her to her feet.

As he helped Hatsue up, the boy remembered with shame how he had lain in wait for her a while ago, had given that whistled signal, had followed after her: even though his actions had been prompted by the circumstances, to him they still seemed to smack of evil. Making no move to repeat yesterday’s caress, he brushed the dirt off the girl’s clothing as gently as though he were her big brother. The soil here was mostly dry sand and the dirt brushed off easily. Luckily there was no sign of any damage.

Hatsue stood motionless, like a child, resting her hand on Shinji’s strong shoulder while he brushed her. Then she looked around for the flashlight, which she had dropped. It was lying on the ground behind them, still throwing its faint, fan-shaped beam, showing the ground covered with pine needles. The island’s heavy twilight pressed in upon this single area of faint light.

“Look where it landed! I must have thrown it behind me when I fell.” The girl spoke in a cheerful, laughing voice.

“What made you so mad?” Shinji asked, looking her full in the face.

“All that talk about you and Chiyoko-san.”

“Stupid!”

“Then there’s nothing to it?”

“There’s nothing to it.”

The two walked along side by side, Shinji holding the flashlight and guiding Hatsue along the difficult path as though he were a ship’s pilot. There was nothing in particular

to say, so the usually silent Shinji began to talk stumblingly to fill in the silence:

“As for me, some day I want to buy a coastal freighter with the money I’ve worked for and saved, and then go into the shipping business with my brother, carrying lumber from Kishu and coal from Kyushu.… Then I’ll have my mother take it easy, and when I get old I’ll come back to the island and take it easy too.… No matter where I sail, I’ll never forget our island.… It has the most beautiful scenery in all Japan”—every person on Uta-jima was firmly convinced of this—“and in the same way I’ll do my best to help make life on our island the most peaceful there is anywhere … the happiest there is anywhere.… Because if we don’t do that, everybody will start forgetting the island and quit wanting to come back. No matter how much times change, very bad things—very bad ways—will all always disappear before they get to our island.… The sea—it only brings the good and right things that the island needs … and keeps the good and right things we already have here.… That’s why there’s not a thief on the whole island—nothing but brave, manly people—people who always have the will to work truly and well and put up with whatever comes—people whose love is never double-faced—people with nothing mean about them anywhere.…”

Of course the boy was not so articulate, and his way of speaking was confused and disconnected, but this is roughly what he told Hatsue in this moment of rare fluency.

She did not interrupt, but kept nodding her head in agreement with everything he said. Never once looking bored, her face overflowed with an expression of genuine

Sympathy and trust, all of which filled Shinji with joy.

Shinji did not want her to think he was being frivolous, and at the end of his serious speech he purposely omitted that last important hope that he had included in his prayer to the sea-god a few nights before.

There was nothing to hinder, and the path continued hiding them in the dense shadows of the trees, but this time Shinji did not even hold Hatsue’s hand, much less dream of kissing her again. What had happened yesterday on the dark beach—to them that seemed not to have been an act of their own volition. It had been an undreamed-of event, brought about by some force outside themselves; it was a mystery how such a thing had come about. This time, they barely managed to make a date to meet again at the observation tower on the afternoon of the next time the fishing-boats could not go out.

When they emerged from the back of Yashiro Shrine, Hatsue gave a little gasp of admiration and stopped walking. Shinji stopped too.

The village was suddenly ablaze with brilliant lights. It was exactly like the opening of some spectacular, soundless festival: every window shone with a bright and indomitable light, a light without the slightest resemblance to the smoky light of oil lamps. It was as though the village had been restored to life and come floating up out of the black night.… The electric generator, so long out of order, had been repaired.

Outside the village they took different paths, and Hatsue went on alone down the stone steps and into the village, lit again, after such a long time, with street lamps.

T

HE DAY CAME

for Shinji’s brother, Hiroshi, to go on the school excursion. They were to tour the Kyoto-Osaka area for six days, spending five nights away from home. This was the way the youths of Uta-jima, who had never before left the island, first saw the wide world outside with their own eyes, learning about it in a single gulp. In the same way, schoolboys of an earlier generation had crossed by boat to the mainland and stared with round eyes at the first horse-drawn omnibus they had ever seen, shouting: “Look! Look! A big dog pulling a privy!”

The children of the island got their first notions of the world outside from the pictures and words in their school-books rather than from the real things. How difficult, then, for them to conceive, by sheer force of imagination, such things as streetcars, tall buildings, movies, subways,

But then, once they had seen reality, once the novelty of astonishment was gone, they perceived clearly how useless it had been for them to try to imagine such things, so much so that at the end of long lives spent on the island they would no longer even so much as remember the existence of such things as streetcars clanging back and forth along the streets of a city.

Before each school excursion Yashiro Shrine did a thriving business in talismans. In their everyday lives the island women committed their own bodies, as a matter of course, to the danger and the death that lurked in the sea, but when it came to excursions setting forth for gigantic cities they themselves had never seen, the mothers felt their children were embarking on great, death-defying adventures.