The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (3 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

Further details of our methods can be found at:

www.equalitytrust.org.uk

Material Success,

Social Failure

I care for riches, to make gifts to friends, or lead a sick man back to health with ease and plenty. Else small aid is wealth for daily gladness; once a man be done with hunger, rich and poor are all as one. Euripides,

Electra

It is a remarkable paradox that, at the pinnacle of human material and technical achievement, we find ourselves anxiety-ridden, prone to depression, worried about how others see us, unsure of our friendships, driven to consume and with little or no community life. Lacking the relaxed social contact and emotional satisfaction we all need, we seek comfort in over-eating, obsessive shopping and spending, or become prey to excessive alcohol, psychoactive medicines and illegal drugs.

How is it that we have created so much mental and emotional suffering despite levels of wealth and comfort unprecedented in human history? Often what we feel is missing is little more than time enjoying the company of friends, yet even that can seem beyond us. We talk as if our lives were a constant battle for psychological survival, struggling against stress and emotional exhaustion, but the truth is that the luxury and extravagance of our lives is so great that it threatens the planet.

Research from the Harwood Institute for Public Innovation (commissioned by the Merck Family Foundation) in the USA shows that people feel that ‘materialism’ somehow comes between them and the satisfaction of their social needs. A report entitled

Yearning for Balance

, based on a nationwide survey of Americans, concluded that they were ‘deeply ambivalent about wealth and material gain’.

1

*

A large majority of people wanted society to ‘move away from greed and excess toward a way of life more centred on values, community, and family’. But they also felt that these priorities were not shared by most of their fellow Americans, who, they believed, had become ‘increasingly atomized, selfish, and irresponsible’. As a result they often felt isolated. However, the report says, that when brought together in focus groups to discuss these issues, people were ‘surprised and excited to find that others share[d] their views’. Rather than uniting us with others in a common cause, the unease we feel about the loss of social values and the way we are drawn into the pursuit of material gain is often experienced as if it were a purely private ambivalence which cuts us off from others.

Mainstream politics no longer taps into these issues and has abandoned the attempt to provide a shared vision capable of inspiring us to create a better society. As voters, we have lost sight of any collective belief that society could be different. Instead of a better society, the only thing almost everyone strives for is to better their own position – as individuals – within the existing society.

The contrast between the material success and social failure of many rich countries is an important signpost. It suggests that, if we are to gain further improvements in the real quality of life, we need to shift attention from material standards and economic growth to ways of improving the psychological and social wellbeing of whole societies. However, as soon as anything psychological is mentioned, discussion tends to focus almost exclusively on individual remedies and treatments. Political thinking seems to run into the sand.

It is now possible to piece together a new, compelling and coherent picture of how we can release societies from the grip of so much dysfunctional behaviour. A proper understanding of what is going on could transform politics and the quality of life for all of us. It would change our experience of the world around us, change what we vote for, and change what we demand from our politicians.

In this book we show that the quality of social relations in a society is built on material foundations. The scale of income differences has a powerful effect on how we relate to each other. Rather than blaming parents, religion, values, education or the penal system, we will show that the scale of inequality provides a powerful policy lever on the psychological wellbeing of all of us. Just as it once took studies of weight gain in babies to show that interacting with a loving care-giver is crucial to child development, so it has taken studies of death rates and of income distribution to show the social needs of adults and to demonstrate how societies can meet them.

Long before the financial crisis which gathered pace in the later part of 2008, British politicians commenting on the decline of community or the rise of various forms of anti-social behaviour, would sometimes refer to our ‘broken society’. The financial collapse shifted attention to the broken economy, and while the broken society was sometimes blamed on the behaviour of the poor, the broken economy was widely attributed to the rich. Stimulated by the prospects of ever bigger salaries and bonuses, those in charge of some of the most trusted financial institutions threw caution to the wind and built houses of cards which could stand only within the protection of a thin speculative bubble. But the truth is that both the broken society and the broken economy resulted from the growth of inequality.

WHERE THE EVIDENCE LEADS

We shall start by outlining the evidence which shows that we have got close to the end of what economic growth can do for us. For thousands of years the best way of improving the quality of human life was to raise material living standards. When the wolf was never far from the door, good times were simply times of plenty. But for the vast majority of people in affluent countries the difficulties of life are no longer about filling our stomachs, having clean water and keeping warm. Most of us now wish we could eat less rather than more. And, for the first time in history, the poor are – on average – fatter than the rich. Economic growth, for so long the great engine of progress, has, in the rich countries, largely finished its work. Not only have measures of wellbeing and happiness ceased to rise with economic growth but, as affluent societies have grown richer, there have been long-term rises in rates of anxiety, depression and numerous other social problems. The populations of rich countries have got to the end of a long historical journey.

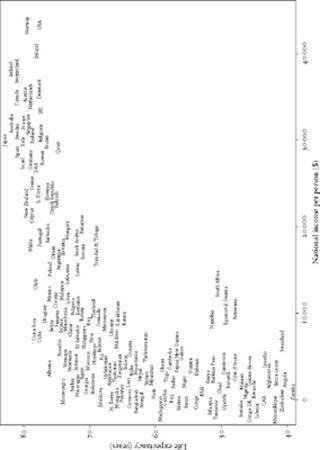

The course of the journey we have made can be seen in Figure 1.1. It shows the trends in life expectancy in relation to Gross National Income per head in countries at various stages of economic development. Among poorer countries, life expectancy increases rapidly during the early stages of economic development, but then, starting among the middle-income countries, the rate of improvement slows down. As living standards rise and countries get richer and richer, the relationship between economic growth and life expectancy weakens. Eventually it disappears entirely and the rising curve in Figure 1.1 becomes horizontal – showing that for rich countries to get richer adds nothing further to their life expectancy. That has already happened in the richest thirty or so countries – nearest the top right-hand corner of Figure 1.1.

The reason why the curve in Figure 1.1 levels out is not because we have reached the limits of life expectancy. Even the richest countries go on enjoying substantial improvements in health as time goes by. What has changed is that the improvements have ceased to be related to average living standards. With every ten years that passes, life expectancy among the rich countries increases by between two and three years. This happens regardless of economic growth, so that a country as rich as the USA no longer does better than Greece or New Zealand, although they are not much more than half as rich. Rather than moving out along the curve in Figure 1.1, what happens as time goes by is that the curve shifts upwards: the same levels of income are associated with higher life expectancy. Looking at the data, you cannot help but conclude that as countries get richer, further increases in average living standards do less and less for health.

While good health and longevity are important, there are other components of the quality of life. But just as the relationship between health and economic growth has levelled off, so too has the relationship with happiness. Like health, how happy people are rises in the early stages of economic growth and then levels off. This is a point made strongly by the economist, Richard Layard, in his book on happiness.

3

Figures on happiness in different countries are probably strongly affected by culture. In some societies not saying you are happy may sound like an admission of failure, while in another claiming to be happy may sound self-satisfied and smug. But, despite the difficulties, Figure 1.2 shows the ‘happiness curve’ levelling off in the richest countries in much the same way as life expectancy. In both cases the important gains are made in the earlier stages of economic growth, but the richer a country gets, the less getting still richer adds to the population’s happiness. In these graphs the curves for both happiness and life expectancy flatten off at around $25,000 per capita, but there is some evidence that the income level at which this occurs may rise over time.

4

Figure 1.1

Only in its early stages does economic development boost life expectancy.

2

The evidence that happiness levels fail to rise further as rich countries get still richer does not come only from comparisons of different countries at a single point in time (as shown in Figure 1.2). In a few countries, such as Japan, the USA and Britain, it is possible to look at changes in happiness over sufficiently long periods of time to see whether they rise as a country gets richer. The evidence shows that happiness has not increased even over periods long enough for real incomes to have doubled. The same pattern has also been found by researchers using other indicators of wellbeing – such as the ‘measure of economic welfare’ or the ‘genuine progress indicator’, which try to calculate net benefits of growth after removing costs like traffic congestion and pollution.

So whether we look at health, happiness or other measures of wellbeing there is a consistent picture. In poorer countries, economic development continues to be very important for human wellbeing. Increases in their material living standards result in substantial improvements both in objective measures of wellbeing like life expectancy, and in subjective ones like happiness. But as nations join the ranks of the affluent developed countries, further rises in income count for less and less.

This is a predictable pattern. As you get more and more of anything, each addition to what you have – whether loaves of bread or cars – contributes less and less to your wellbeing. If you are hungry, a loaf of bread is everything, but when your hunger is satisfied, many more loaves don’t particularly help you and might become a nuisance as they go stale.