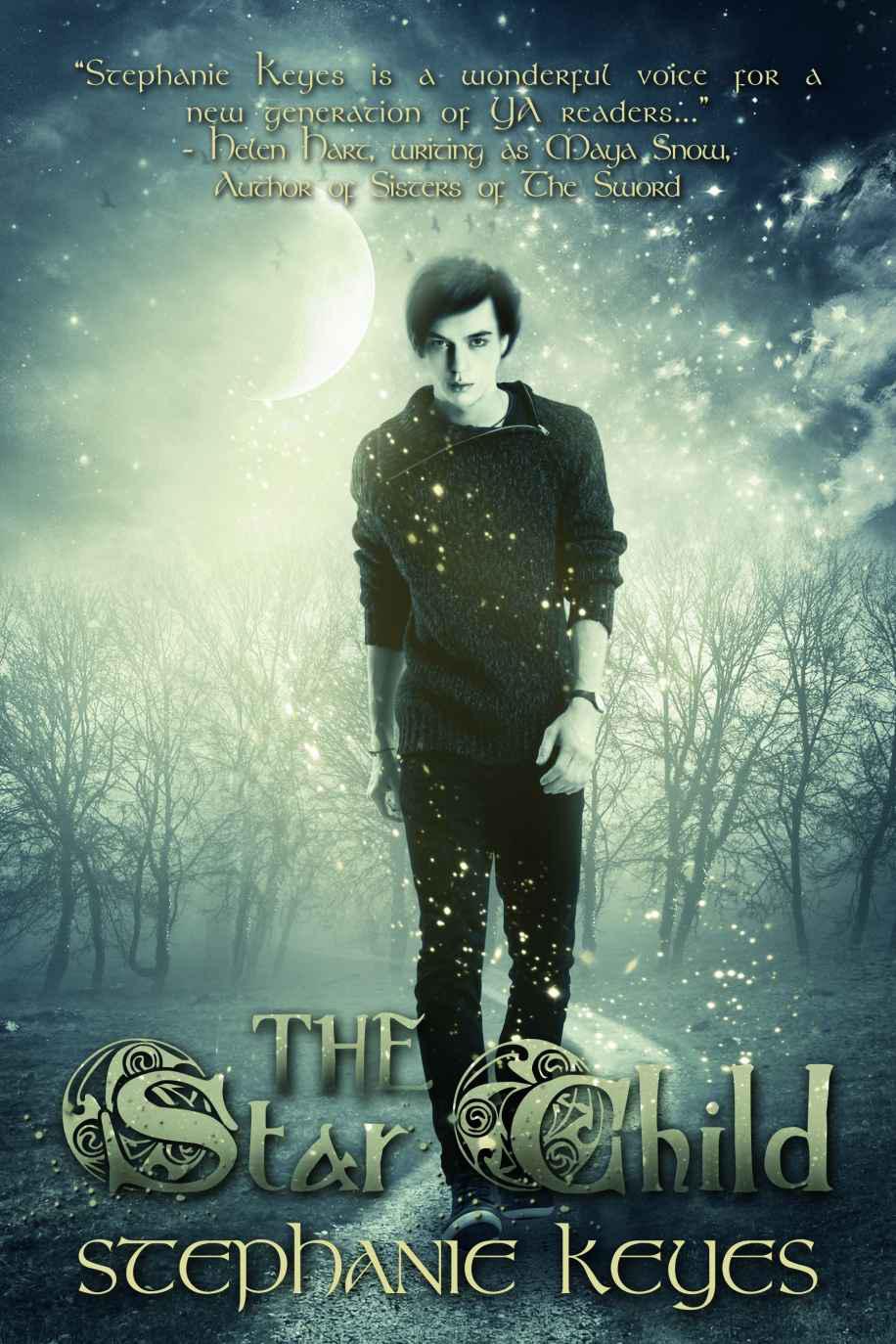

The Star Child (The Star Child Series)

Read The Star Child (The Star Child Series) Online

Authors: Stephanie Keyes

The Star Child

Stephanie Keyes

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, places, or events is coincidental and not intended by the author.

If you purchase this book without a cover you should be aware that this book may have been stolen property and reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher. In such case the author has not received any payment for this “stripped book.”

The Star Child

Copyright © 2012 Stephanie Keyes

All rights reserved.

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-9856562-4-9

ePub ISBN: 978-0-9856562-3-2

Inkspell Publishing

18, Scott Court, C-4

Ridgefield Park

07660 NJ

Edited By Melissa Keir.

Cover art By Najla Qamber

You can visit us at www.inkspellpublishing.com

This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission. The copying, scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic or print editions, and do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

The Star Child is dedicated to the memory of my father, Russ Jones.

CHAPTER ONE

GRADUATION DAY

My eyes snapped open. For a moment, I looked around the room, trying to recall where I was, the time of day, and what I’d been doing before falling asleep. I couldn’t remember what I’d been dreaming about specifically, though I had a good idea.

Rubbing my eyes wearily, the rushing in my ears subsided as I sat up and began the return journey to my current reality. It was my college graduation day and I’d be the youngest student in three generations to graduate with a degree from the prestigious Yale University.

Great.

More attention.

My ears popped. Able to hear again, I realized that Gabe, my roommate, was talking to me as he ran around the room packing up the last of his belongings. It was a task that he’d put off for quite some time, as did I, but now I was packed and ready to go.

Normally, our apartment was small and cluttered, but homey. Gabe’s mother had decorated it during the first year that we roomed together. The resulting product was a combination of Senior Citizen and IKEA, almost disturbing but too contemporary to be tacky. Gabe had managed to trash the place within the time that I was sleeping and it looked like a bomb went off.

Looking back at the clock, I stood up. “We really need to leave now.”

Sparing a glance in the mirror, I attempted to tidy up my chin-length black hair before making a lame effort to de-wrinkle my clothes. My suit was well made, tailored in the height of fashion. However, no amount of custom design could save it from my impromptu nap on the sofa. I met my own green eyes in the mirror. This was as good as it was going to get.

Gabe, who’d been rummaging boxes, stopped and threw up his hands. “Yeah, you’re right. There’s plenty of time to get this stuff, right?”

“Sure.” If Gabe wasn’t packed by the end of the day, his entire family would probably come in and pack up his belongings en mass. That was how they did everything, as one large, loud group. I loved them all.

Without another word, we both donned our blue caps and gowns. Grabbing some essentials—keys, cell phone, iPod music player, and a Snickers candy bar, I followed Gabe out the door, taking in a final glance at the room on the way out. I would miss this place; it had been more of a home to me than most of my former dorm accommodations. Still, it was time to say goodbye.

Old Campus and the designated congregation area for graduates was a short walk from our dorm. Despite the lateness of the hour, we took our time cutting across the vast lawns to enjoy the beautiful Connecticut day. When we reached the large group of volunteers that sat behind an endless row of tables, we searched for the table with a large S suspended above it, then got in the short line to register.

“Name?” barked a commencement volunteer.

“Stewart. Gabriel Stewart.” Gabe was adjusting his clothes, most likely uncomfortable about the gown’s cut on his tall frame. He straightened the cap perched atop his head and checked his shoelaces before unfolding himself to his full six-foot-three height.

The volunteer dismissed Gabe with a check of a box and looked at me. “Okay, your name?”

My feet carried me toward to the table. “St. James, Kellen.”

The volunteer didn’t look me in the eyes.

I get that a lot

. After we’d checked in, we went to stand in the large line of graduates with whom we’d walk onto the field.

Gabe, who was two places in front of me, walked back and stood next to me. “So, do you think…do you think your father will come today?” He scratched his head—a behavior he often demonstrated when he was nervous.

The reason for his anxiety was obvious to me: he wanted to know the answer, but he didn’t want to upset me. He wasn’t sure if he should’ve brought it up, and I wished that he hadn’t. My shoes caught my eye. They were polished black loafers with the customary tassel on the front. I stared at them for a moment.

For weeks, I’d been wondering if my father would show at my graduation. I’d certainly held up my end of the bargain, graduating five years early

and

from his alma mater. Would this mean that he’d finally be pleased with me? Call me crazy, but I found myself hoping, though the realist in me cautioned against it. “I really don’t know. He knows the date, but since I only speak to him when absolutely necessary, I’m not holding my breath.”

“But maybe if you talked to him…” Gabe frowned and scratched his head again and knocked his cap off-center.

It was clear that he was unhappy about this turn of events. It was easy to understand his perspective if you thought about it. Gabe had a very close, tight-knit family, and he couldn’t fathom anyone else not having the same.

Sighing, I glared at him. This discussion was old. “Sounds great in theory, but the execution is flawed. He doesn’t have it in him. Besides, I really don’t care if he shows up.”

My father, or Stephen as I often referred to him, had never been there for me, either before or after he’d shipped me off to an expensive boarding school in England, where I’d spent the majority of my school years before coming to Yale. Incidentally, that’s a long way away for a little boy to travel from New York after losing his mother. Not that my feelings had ever mattered to him. We had no relationship, and I refused to bestow upon him the term “father” or even “Dad”. Those titles belonged to a special kind of person. They were honors that he did not deserve.

“If he does come,” said Gabe, “he’s going to be really angry when he finds out that you didn’t take the medical school track or even take the MCATs.”

Snorting, I shared a smile with Gabe. He was right; Stephen would be furious. That would be a fun conversation when he found out that he’d paid the bills for me to study literature and not biology.

It wasn’t in my nature to try to pull one over on Stephen, but he never listened to anything I had to say. When I first enrolled at Yale, I found that he’d pre-registered me for a biology major. I spent the first week vomiting into a garbage can during most of the lessons. Biology clearly wasn’t the right path for me, so I changed my major. My teachers were relieved; so was my lab partner.

Besides, the humanities were clearly my strength. I’d even been called a prodigy when I was five, though I preferred not to think of myself that way. Writing was my first love and I wrote constantly: novels, short stories, anything that came to mind. I’ve always believed that you should play to your strengths. Stephen, on the other hand, wanted a “Doogie Howser, MD” in the family. If you’ve never heard of him, Google it.

I changed my major and convinced Sarah, the cook, who also thought that Stephen was a jerk, to switch the quarterly grade reports that arrived at the house for the fabricated ones that I’d created on my Mac. Thank God for Photoshop.

The procession started and we began our walk onto the field. The graduating class ranged from the pranksters, who were snorting and laughing, to the serious rich boys, with their straightened ties and aristocratic heads held high. We were somewhere in the middle. After taking our seats, the keynote speaker began his commencement address. He was an alumnus and a successful executive who’d founded a charity that donated electronic equipment to underprivileged kids.

The speaker was only about five minutes into his speech when it happened. As I looked past the speaker into the space behind him, there was a spot of green hovering in the air to his right. At first, I assumed that it was a trick of the light or a retinal burn from the sun’s rays. Leaning my head forward, I confirmed that the space was semi-transparent and shimmered before me.

Glancing around, I wondered if anyone else had taken notice. People stared at their shoes, their phones, their programs, everywhere but at me. That told me all that I needed to know: whatever this was, it was meant for me alone. As the green space increased in size, it was suddenly on the move and heading straight for me. It continued until it came to a stop right in front of me, almost at eye level. Looking around, I noticed a change. Everyone seemed frozen, unmoving. Even the light spring breeze that had touched my face only a second ago had stopped.

Exercising caution, I leaned toward the opening. There was music filtering through. The faint sound of pipe and drum got my attention. Inching forward, I brought my face close to the opening and looked inside. On the other side sat my grandmother’s house in the late-day sun.

My stomach dropped. Placing both hands on the base of the opening, I pulled. It gave like Saran Wrap. Tugging on it, I continued this motion until the opening was large enough to step into. Looking back to verify that nothing had changed, I stepped through the hole and onto the grass by Gran’s house in Ireland.

***

Two things I noticed immediately were my change of clothes (I was now sporting a pair of jeans and a hunter green sweater) and my close proximity to the ground. I was no longer seventeen, but instead six years old. Whether this was the dream that I’d memorized so well or something else entirely didn’t matter. Whenever I came to this place in my dreams, I was always six because that’s how old I was when I first met her.

It was the autumn after my mother Addison’s death and I’d come with Stephen and my brother to visit Gran in Ireland. This wasn’t our first trip abroad; Stephen made these pilgrimages annually, insisting that we stay in the home where he was born. Nothing, not even my mother’s death, would dissuade him.

Some people would have regarded him as a caring son for visiting his mother regularly, despite the distance. However, they’d have been vastly mistaken. He visited out of duty, not out of love or concern for Gran. There was always something tainted about him.

The ghostly pangs of loss and loneliness tugged at me now, pulling at my clothes and at the unexplored fringes of my mind. Tearing my gaze from the empty house, I looked to the steps that led down to the cove and started walking toward them.

On that day, the day I met her, I’d gone down to the rocks deliberately to avoid my older brother, Roger. His favorite game involved taunting me verbally, being much too ineffective as a bully to do any damage to me physically. He’d follow me around, telling me how hated and worthless I was.

The cove was my preferred place to visit, though Gran hadn’t exactly deemed me old enough to walk to the cove on my own. Roger, who was generally a wimp, was too afraid to make the journey. He believed the cove was haunted, which meant that this place was safe territory for me. I wasn’t afraid of ghosts. My mother was a ghost

now.

The wind was picking up and blew harshly against my skin, ruffling my hair. The style was rather long for a young boy, and I got picked on a lot in school for the look. I’d refused to have it cut; my mother was the only one who cut my hair. No one was allowed to touch it until I was ten. It was around that time when I’d given up hope that she’d return.