The Starbucks Story (14 page)

Read The Starbucks Story Online

Authors: John Simmons

Starbucks has thrived in almost every market it has entered because it has looked after its relationship with its own people. It knows that brands are ways of making easier connections between people. Everything starts with the attachment between the company and its partners. This results in lower levels of staff turnover; indeed, high levels of retention in a notoriously volatile industry. The relationship with local business partners is important too, because in most international situations Starbucks teams up with a local partner. The only market entry that seems not to have worked – Israel – failed because there was a conflict between the standards Starbucks wished to see (the same as everywhere else) and the standards the partner could deliver. Starbucks withdrew because it felt its brand was being compromised.

That was a blip in a relentless and generally smooth stream of openings in different countries. The Philippines were followed by Taiwan, Thailand, New Zealand and Malaysia, populating the Pacific Rim. The same pattern was followed: hire a local public relations company, eschew advertising, select a flagship location, produce local artwork, retain the core products, adapt fringe products to local tastes, and produce everything to high quality with friendly, trained baristas. These have become entrenched principles.

There is a deeply held belief that word of mouth is more authentic, honest and effective than advertising for Starbucks. That puts more responsibility on the brand, and particularly its people, to deliver. So Starbucks takes great care when selecting the right business partners for different markets around the world who will understand its standards and take them to heart. When recruiting starts, new partners (managers and also, at least for first stores, baristas) will be brought to Seattle for training and immersion in the practicalities and the principles. Training lasts between 12 and 16 weeks. Standards for quality, cleanliness, service and speed apply internationally, but the personality of the barista is seen everywhere as the essential expression of the Starbucks brand. The aim is to connect with customers, not just hurry them through. But in the US speed is all-important, whereas in Japan meticulousness is what matters, and people are more prepared to wait in line.

Starbucks started to learn these nuances and find ways to introduce flexibility to local markets. Much of this comes down to trust: everyone trusting the brand, and Starbucks trusting its partners. Local autonomy and personal responsibility are vital to the way Starbucks operates. Two-thirds of employees are part-timers, but Starbucks has always made a point of treating its part-time staff with equity (literally in the sense that stock options are offered to part-timers, too). Clearly it is likely to be more difficult to establish trust with employees who have a lesser commitment in terms of hours worked. But if they were to show less commitment in their work, it would undermine the brand, so efforts are taken to look after people well whether they are full-time or part-time. At the same time, there is a realization and a deep belief that adherence to its principles is an important element of the contract with employees: “If we compromised on quality or on our values, we would have a revolt,” said Orin Smith.

This starts to sound almost military in its planning and precision, but the reality is inevitably different. Starbucks remains an entrepreneurial company, perhaps especially in international markets. It has learned to go with its intuition, and this has led to some developments that admittedly are opportunistic. Soon after the opening in Japan, Starbucks was approached by “some great people” (Orin Smith’s words). The opportunity was to work in partnership with a local company to open Starbucks stores in the Philippines. The market research suggested that the Philippines was a relatively poor country, and the national income levels might not support much of a Starbucks presence. However, there was a good rapport with the potential partners, so a deal was struck and Starbucks opened in the Philippines in 1997. Beyond all expectations, its presence has grown to more than 50 stores in six years.

I interviewed Orin Smith with two French journalists from

Figaro

and

Le Monde

. The journalists kept returning to the question of prices. “What is the price of a Starbucks coffee in Indonesia? What is the average weekly wage?” Knowing that the two answers are far closer than in the US, they kept professing surprise. If Starbucks were simply a product, their surprise would be understandable, but its success in the Philippines represents clear proof that it is in fact a true brand. People are willing to pay a relatively high price for what they perceive as a treat, a just-affordable luxury, because they are buying much more than simply a cup of coffee.

Asia was well on the way to being Starbucks adopters. Europe beckoned. You sense that there was a slight holding of breath at the prospect. Howard Schultz, in particular, had always regarded Europe and its coffee house tradition in some awe. It seemed that little education would be needed: Europeans understood coffee more deeply than people in other parts of the world. But that made the whole thing all the more challenging. The UK, however, seemed the natural place to start. There were no language difficulties if we discount George Bernard Shaw’s dictum about two countries divided by a common language. And there was a chain called the Seattle Coffee Company, with 65 retail locations, that Starbucks could acquire.

The Seattle Coffee Company, as you might imagine from its name, had been built on the Starbucks model by people who had Starbucks connections. It was a benign acquisition: the two companies had a lot in common, including a shared interest in books and literacy. The Seattle Coffee Company was one of the coffee companies that had opened outlets within Waterstone’s, the UK’s leading bookseller. In the US, Starbucks had had stores within Barnes & Noble bookshops since 1993. The association seemed right to enter into the traditional spirit of European coffee houses as places for ideas and intellectual stimulation. The acquisition went ahead in 1998 and the Seattle Coffee Company stores were quickly rebranded as Starbucks. Overnight, as it appeared to British observers, Starbucks had established itself in the UK.

It took time for this to work financially. Orin Smith smiles ruefully at the cost of British high street rents. Some mistakes were made with locations; some of these mistakes were inherited. Although business was good in terms of people in the coffee houses, it took some time to work towards profitability. Since 2002 this has started to happen, as Starbucks has settled into the market and begun to feel the strength of its brand principles. In particular, the community aspect of the brand (about which I will say more in the next chapter) speaks well to British people, who have a strong identification with the places where they live and work – and a natural tendency to be suspicious of outsiders. With the passing of time Starbucks is seen as less of an outsider as word gently spreads of its involvement in local and national good causes. The UK has grown to be Starbucks’ third biggest market in the world, behind the US and Japan.

Cathy Heseltine, the marketing director for Starbucks in the UK, is conscious of simultaneously modeling the UK Starbucks on its antecedents and finding a unique voice and style for the local market. The brand is multilayered, and little is written down by way of rules or definitions. This gives Starbucks in the UK the flexibility to play slightly different tunes around the pillars of the product itself, commitment to social responsibility and the in-store experience. At the same, time there is a determination not to mess with things. Respect and dignity are the starting points for the Starbucks working experience in the UK just as in the US. The emphasis lies on recruiting the right people, training them well (in the London equivalent of the Seattle support center) and building retention by encouraging adult relationships with the company and communities. In the spirit of “It’s coffee, stupid,” there is a constant reminder of the business’s starting point – meetings begin with a coffee tasting.

While the coffee is the immutable core of the experience, other products reflect local tastes. Granola bars sell well in the UK but have yet to make the flight across the Atlantic or the Channel. A new variety of Frappuccino – strawberries and cream – was developed initially for Wimbledon tennis fortnight, but has now been extended to a year-round product. Innocent Drinks, one of the youngest and trendiest brands around, was brought in to develop a new range of fruit drinks for UK stores. “Juicy waters” are selling well, and the Innocent brand provides a complementary, but not threatening, association for Starbucks.

If Starbucks in the UK has been a patient process, putting down ever deeper roots in communities, success came more quickly in other overseas markets. Hong Kong and Korea were immediately profitable, and the Middle East has grown quietly as Starbucks adapted its style to local sensitivities. “Who will be attracted to Starbucks stores?” is always a key question in the developed markets. The demographic profile has been steadily broadening, but the brand appeals to a wide range of people worldwide. In Arabic countries there are special issues, including the separation of the sexes in Saudi Arabia. The way to handle this is partly shown by the discovery that in the Middle East, the “average customer” is a family, so Starbucks stores are divided into men-only and family areas. Each market has a slightly different take on Starbucks; each market adds a local layer to the mix. In South Korea, this extends to trading in the biggest and tallest Starbucks in the world, a building of five storeys.

Perhaps the most surprising place to find a Starbucks was in Beijing. I had gone there as a tourist over the Millennium New Year and was making my way to the Forbidden City when I came across a Starbucks. Stepping inside, smelling the coffee, hearing the music, I encountered the authentic Starbucks experience. It was not a Chinese experience, though. Starbucks has grown especially fast in Shanghai, opening 15 stores within a year, and South China has become a thriving region. The appeal for the local audience is largely to do with its foreignness and association with comfort, luxury and freedom, qualities that the nation was denied for many years. Starbucks stores are now seen as beacons of China’s changing social and commercial environment.

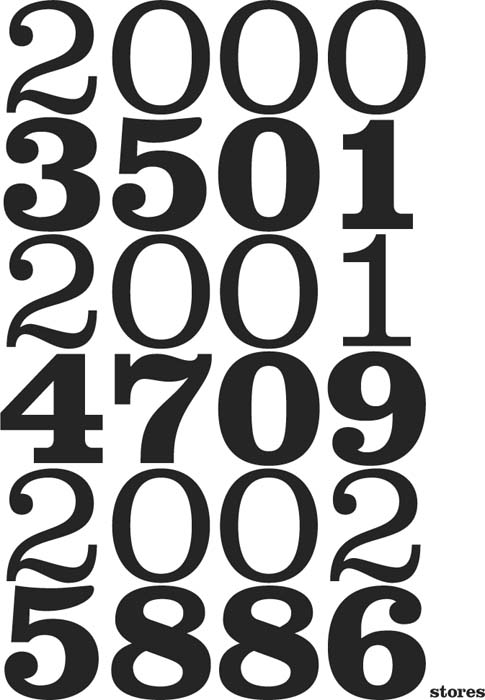

By the end of 2000, there were 3,501 Starbucks stores worldwide; by the end of 2001, 4,709; a year later, 5,886. The latest total, at the beginning of 2004, is 7,500. New shops are opening at the rate of three a day. Like an empire, the sun never sets on Starbucks. Size always carries dangers, particularly if growth is seen as greedy, but Starbucks has gained a momentum that is hard to stop. There are now Starbucks stores in every US state, yet the market is still relatively untouched (Starbucks has only a 7 percent share of “coffee opportunities” in North America as a whole). Starbucks is located in 34 different countries around the world, yet its purchases represent only 1 percent of the world’s coffee; Kraft, Nestlé and Procter & Gamble buy much greater proportions at much lower prices. Even so, Starbucks’ visible presence is much more apparent than any of these economically more powerful companies.

Although there are no immediate limits to growth, Starbucks depends on its ability to maintain good relationships, particularly with the local communities where it operates and the farming communities where it sources its coffee. Its ability to grow depends on the goodwill it can keep generating in the widest possible constituency. The conundrum for Starbucks is to grow big worldwide while retaining the soul of a small company based in Seattle.

TIMELINE

1971

Seattle

1972

1973

1974

1975

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

North-western USA, Canada

1988

1989

1990

1991

California

1992

1993

Washington DC