The Starbucks Story (10 page)

Read The Starbucks Story Online

Authors: John Simmons

The business now had its immediate investment needs sorted out, and a mechanism in place to raise further funds in the future. It could concentrate on meeting its aims, and the expansion plan could proceed at a fast pace. Fifty new stores opened in 1992 and 100 in 1993, including Washington DC as the first location on the east coast. But competition was growing. The basic components of the Starbucks model were easy to imitate. The espresso business was easy to enter. To open an espresso bar became an attainable dream for many American victims of corporate downsizing.

Starbucks had its Seattle experience to draw on. The phenomenon there had been that Starbucks had grown the market for coffee drinking. The original “mom and pop” coffee shop continued to thrive. New competitors to Starbucks came in, and the good ones survived. But Starbucks itself seemed to feed off the market conditions it created. Despite constant predictions that the market in individual cities could not sustain so many coffee shops, another Starbucks would open and it would soon fill with people.

The reader can assume that, for the rest of this narrative, new Starbucks shops continued to open. Fewer than 10 shops in 1987 had grown to more than 7,500 in 2003, a phenomenal expansion. The details of that story are not what will concern us for the rest of this book because the pattern had by now been established and would be repeated. The foundations of the brand were strong, enabling growth on solid ground. From here on, we will focus on decisive moments that have tested the brand and demonstrated both its fundamental strength and its ability to keep changing in a positive way.

Growth presents any brand with a challenge to its core products. Are these products inviolable and immutable? Should they adapt over time in response to new trends or developing customer tastes? The traditionalist Starbucks view, inherited from its founding fathers, was that the coffee itself was sacred. There was an Italian way that had become the Starbucks way, and no deviation from it would be countenanced. The debate came to a head over the issue of low-fat milk. The purist view had it that Starbucks’ lattes and cappuccinos should be made only with whole-fat milk; the coffee tasted better that way. But many customers disagreed and wanted skimmed milk, whether for taste or health reasons. If denied it, they simply went to a rival coffee shop down the road.

For Howard Schultz and many others, this was a fundamental brand issue. It was for Howard Behar too, but he had a more flexible view and as always championed the customer’s cause. As long as the coffee itself remained true to Starbucks’ quality standards, customers should be allowed to customize their drinks in whatever way they wanted. So the skinny latte was born, and today it outsells the whole-milk version.

This step ushered in a whole range of product development possibilities. Syrups of different flavors had already been introduced, although a firm decision had been taken never to add artificial flavors to the beans themselves.

*

But a more significant piece of product development was under development in 1994. As I write these words in the Starbucks store on the corner of 4th and Seneca in Seattle, I suspect that one of the biggest changes over the past ten years has been the nature and size of the menu. It is still not vast compared to, say, the all-encompassing choice of a New York diner where the menu can be the start of further exploration and negotiation, but you can have an extraordinary variety of coffee-based drinks. And Frappuccino now has a panel of the menu board all to itself.

In 1994, presented with the prototype that was to become Frappuccino, Howard Schulz’s instinct was to reject it. The idea for the beverage had originated in southern California, no doubt spurred by the temperature. Customers wanted a cold drink. Starbucks offered a cold latte with ice cubes. Nearby coffee shops offered coffee granitas. Dina Campion was the district manager for 10 Starbucks stores around Santa Monica, and she obtained a blender that she installed in one of her stores. This filled a gap but everyone involved realized the experiment needed development, so it was taken to the R&D department in Seattle.

The department developed a product that used powder, and offered it back to the Californian stores. Rather than smiling and being polite to the management, two other Starbucks partners, Ann Ewing and Greg Rogers, then carried out their own development of the drink. First to go was the powder, replaced by freshly brewed coffee. Variations were made in the other ingredients and the blending process: lowfat milk, more ice, longer blending time. When they tried the result out on customers, it got an enthusiastic response.

Soon the drink was presented to Howard Behar alongside the “official” powder-based version. He had no doubts, and saw that customers preferred the unofficial version, too. Additional development and customer research led to further refinements, and Frappuccino was launched in all Starbucks in the summer of 1995. The name was simply a piece of good fortune. The previous year, Starbucks had acquired a Boston company called The Coffee Connection that had an unsuccessful drink called Frappuccino. The combination of

frappé

(from the French, meaning “chilled”) with

cappuccino

gave the name all the advantages of being meaningful, understandable and easy to say.

The importance of the Frappuccino story is that it showed Starbucks developing a significant new product for the first time in its history. It developed the product by keeping true to its brand principles. The development process used the creativity and innovation of Starbucks partners, who listened hard to customers. The new product was based on fresh coffee, so Frappuccino was seen as a coffee beverage, not a milk one. And, of course, it was an amazing commercial success, with Starbucks selling $52 million of Frappuccinos in the first full year of operation (7 percent of annual revenues at that time).

There was more to come. Late in 1994, Starbucks and Pepsi formed the North American Coffee Partnership to create new coffee-related products for mass distribution in bottles or cans. The first result of this partnership was a fizzy coffee drink called Mazagran which sounds as if you should be obtaining it on prescription from your pharmacy. Although some people claimed that it tasted really good, sales were slow and the joint venture was wobbling. The in-store success of Frappuccino came to the rescue. It was agreed that, if a version of Frappuccino could be developed that tasted like the store-made version and then sold in a bottle with an acceptable shelf life, Pepsi would put it into production and distribute it nationally. The technical problems were overcome and, launched on a wave of confidence, Frappuccino went on sale in west coast supermarkets in 1996 without any test marketing. In fact, the partnership wildly underestimated the appeal of Frappuccino. It sold so well that they had to withdraw marketing support and then halt production until manufacturing capacity could be increased to meet the level of demand. Starbucks made its then largest investment in a new bottling plant. In summer 1997, Frappuccinos were launched into supermarkets nationwide.

The relationship with Pepsi throws up some interesting questions about the Starbucks brand. Starbucks believes in people and communities, and acts on that belief through volunteering and practical action. The focus of each Starbucks store is local. The company has become big, but remains focused on the small. In many ways Pepsi seems its antithesis: one of those juggernaut American brands that crushes all before it. Howard Schultz insists that experience has proved otherwise. Starbucks has undoubtedly gained an enormous increase in its reach through its partnership with Pepsi, but it has not had to compromise any element of its products or brand. You cannot buy a Pepsi-Cola in Starbucks stores because a big-name brand would detract from the Starbucks brand. The only advantage to Pepsi seems to be the commercial one of being able to turn a profit from bottling and distributing Starbucks’ products. On the other hand Starbucks takes decisions that are in its commercial interest, but it will never take a commercial decision (however financially attractive it might seem) if that decision risks undermining the Starbucks brand and culture in any way.

In late 2003, Howard Schultz told me a story from around the time of the Pepsi partnership. The boss of a national cable company met Howard and within minutes of the meeting starting, laid a blank cheque on the table in front of him. “Here you are, fill in whatever figure you want,” said the cable man. Howard asked what Starbucks would have to give in return. “Let us install monitors and broadcast TV in the corners of your stores.” The cheque remained blank and was pushed back across the table. TVs would destroy the idea of the third place on which the brand was based.

In 1995, the possibility of another joint venture presented itself, and this too was controversial. It called into question the balance between the integrity of the brand and commercial growth. A brand that is to grow, and continue growing, depends absolutely on trust, particularly the trust vested in it by its own people and by customers. The decision to serve Starbucks’ coffee on United Airlines’ planes threatened to undermine that trust.

The decision came about because United discovered, as every airline must know, that its customers hated its coffee. United wanted to do something about it, so talks started with Starbucks about supplying coffee that would be brewed and dispensed at more than 30,000 feet. The potential advantage to United was clear: its customers would have better coffee and another reason to be loyal to United. The potential advantage to Starbucks was also clear: it would double the number of people it was reaching. But the potential disadvantage to Starbucks was equally clear. If it could not deliver an improvement in the quality of the airline coffee, its brand and reputation would be severely damaged. This was a high-risk strategy, and many people in Starbucks were anxious and uncertain about it.

The figures were certainly tempting. United flew 80 million people a year on 500 planes to all parts of the world. Up to 40 percent of them asked for coffee. There’s an awful lot of coffee in the air, and a lot of awful coffee, too. The prospect of reaching and educating an extra 20 million or more people was irresistible, particularly for a company about to embark on a program of international expansion. The Starbucks brand could travel the world to reach new markets without even opening an overseas store.

If the figures were tempting, the challenges were daunting. Extra new equipment on board seemed unlikely to be acceptable given that airlines try constantly to reduce weight. Water quality would vary according to the country where it was taken on board. Over 22,000 flight attendants would need to be trained as baristas.

At first, Starbucks turned down the opportunity because the risks were too high. What use would 20 million captive customers be if their first encounter with Starbucks left the impression that it made terrible coffee? United was upset by the decision, and kept trying to convince Starbucks of its sincerity and willingness to meet the standards needed. Negotiations resumed. United bent over backwards to get Starbucks on board.

Eventually a deal was done that gave Starbucks an unusual degree of quality control over its bigger partner’s operation. Equipment would be improved; all flight attendants would be specially trained; a quality-assurance program covering every aspect of coffee-making would be introduced. United was paying for all this, and also for an advertising campaign in major business media to promote the fact that Starbucks’ coffee would now be served on United planes. The ad line ran: “After all, we don’t just work here. We have to drink the coffee, too.” For the first time Starbucks had the exposure of national advertising, and it did not have to pay for it.

Everything seemed set fair, but it started badly. There were teething problems with phasing out old stocks of coffee and with the operation of the equipment. The coffee still tasted bad. Starbucks insisted that United had to improve. And within months, United did. After a few months a survey showed that 71 percent of coffee drinkers described the coffee as excellent or good.

*

Starbucks had changed in an extraordinary way. It could no longer see itself or be seen as a little regional company. It was a public company performing well on Wall Street; it was in partnership with some of the biggest names in corporate America; it was being talked about in every part of the US even though its actual coverage was patchy. It had also undergone another paradigm shift. In 1984, the first shift had meant that Starbucks offered a coffee experience, not just coffee beans. Now, in the middle 1990s, it had moved its products and brand outside the four walls of its stores into different places where it could reach many more people without needing to increase resources massively.

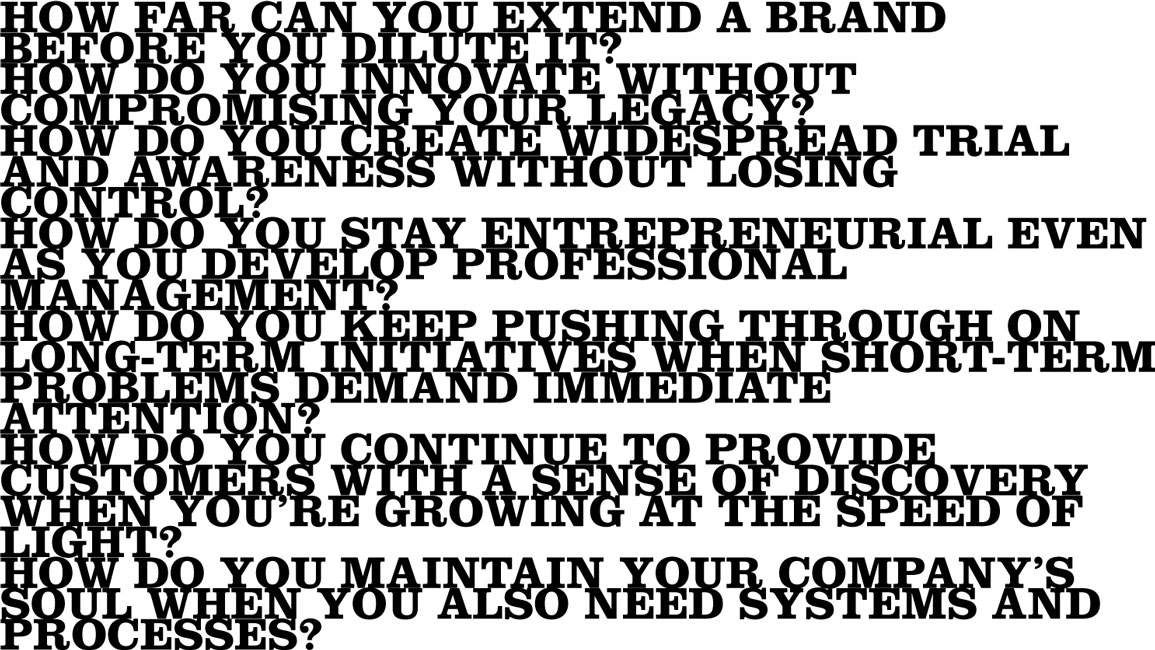

At this point it was clear that Starbucks had to do two things. First, it needed to take the logical step of international expansion, to step off one of those United planes into a foreign country and test the concept there. Howard Behar was put in charge of international development. Second, Starbucks had to get serious about marketing. Howard Schultz was a marketing man by instinct, and his instinct told him that he needed help to keep Starbucks moving forward in ways that remained true to his understanding of the brand that he had created. He knew that the brand was now out of his control – it was out there being represented by thousands of partners who had bought his vision – but he also knew that nothing was more crucial to the continuing success of the business than continuing belief in the brand. Reinvention was the word he used and still uses to describe the next challenge for Starbucks. In his own words: