The Steam-Driven Boy (12 page)

‘Good God!’ said Strathnaver. ‘The poor wretch has made himself credentials. This is no more a coin than I am. Hoho, Mr Gates, I must give you a lesson in minting, someday. When you design a die, you must

reverse

the image, so that it comes out proper on the coin.’

He passed the coin round, and we could all see that the inscription was backwards. It was poor forgery.

‘Things have got reversed somehow!’ shouted Gates. ‘I don’t know how. What can I do to make you believe me?’

‘Nothing on earth,’ said Jones. ‘The last knave shewed me a curious engine he called a Lighter – but when I examined it, ’twas nothing but a tiny oil-wick lamp with a matchlock flint attached.’

‘I’ll take you back to my own time, and that will convince you!’

‘A pretty idea,’ said Mr Strathnaver, ‘but you’ll never get him away from the fire.’

‘What?’ said Jones. ‘Quit the fire to wander about in the aguey snow until this rascal’s fellows waylay me and kill me? I cannot say I like the prospect.’

‘Oh, we needn’t go far,’ said Gates. ‘My Time Machine is very close by – and some of your friends can follow and watch. Can it be you are afraid to prove me right?’

For once, Jones had no answer. He leapt up with surprizing agility and signalled for his cloak and hat. ‘Let us see it, you dog,’ he rumbled.

Dick Blackadder and I were elected to follow. We went but twenty paces in the snow when we encountered the ‘Time Machine’. It was somewhat like a sedan-chair, somewhat like a bathing-machine and no little like an upright coffin on wheels. Gates opened a panel in it, and the two men got themselves inside. The panel closed up.

Dick and I watched the device closely, ready for any trick. All was deathly still.

‘I fear something has happened to Lemuel,’ said Dick. ‘He could never keep silence this long.’

I wrencht at the handle of the panel, but it was fast. An unearthly light seemed to stream from crevices and cracks about the door, increasingly bright. I applied my eye to a crack and peered in.

There was not a soul inside.

The light got brighter and brighter until, with a thunderclap, the entire machine fell to pieces about me. I was knocked flat by the Great Noise, and when I regained my feet, I was amazed to see Dr Jones standing alone amidst the wreckage.

‘Are you hurt, Dr Jones?’ asked Dick, scrambling to his feet.

‘No, I – No.’

‘But where is Mr Gates?’

‘It would seem,’ said Jones, looking about, ‘that he is blown into aeternity.’

We helped him back to the fireside, where, as I recall, he was strangely silent and morose all evening, and would not respond to no amount of badinage. He remained muffled in his cloak and refused to say a word.

That is all I know of the incident, Jerry. Hoping this account is of some good, I remain

Your affectionate

Timothy Scunthe

To Sir Timothy Scunthe, Bart.

Sept. 9

Dear Tim,

Rec’d your story and am truly amazed at the copiousness of your memory and notes. Surely you are more the man to pen a Reminiscence than I. You have captured nicely the flavour of the old Warthog’s speach, and I find your account exact in nearly every Particular.

Do give my regards to Dr Jones and pray him to send me some little item of interest to go in my Reminiscences. If it would not inconvenience him, I would like mightily to hear more of his Experience that strange evening. Eternally gratefull I remain

Your affectionate

Jeremy Botford

Postscript. How is it you say the Doctor has a wart upon the

right

side of his mouth? I have before me a miniature of him, shewing the wan plainly on the

left

.

Yours &c.,

Jer. Botford

To Jeremy Botford, Esq.

Sept. 14

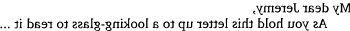

Dear Jerry,

Business is pressing. This is only a brief billet to inform you that I have spoken to Dr J. and he has promised to send you something. ‘But I doubt (said he) that he will want to use it.’ Do you understand this? I confess I do not. More later from

Your affectionate

Timothy Scunthe

To Jeremy Botford, Esq.

Sept. 15

… I hope you will find it in you to pity its author. Do not, I beg you, judge me until you have read here the truth of my plight.

Having departed on December 10, 1762 from the yard of Crutchwood’s, I journeyed into the Future. Having made my jokes about the Twentieth Century, I lived to see them, tragically, become Real. I saw Art & Architecture decline to Nursery Toys, and Literature reduced to Babel. Morality vanished; Science pottered with household Enjines. The main buziness of the time seemed to be World-Wide War, or man-made Catastrophe. Whole cities full of people were ignited and cooked alive.

Betwixt the two wars, people drive about the countryside in great carriage-enjines, which poison the air with harmful vapours. These carriages have o’erlaid the cities with smoak, black and noxious. There is in the Twentieth Century neither Beauty nor Reason, nor any other Mark which sheweth Man more than a beast.

But enough of a sad sojourn to a dismal place. I was sickened by it to near the point of madness. I knew I had done Wrong in accompanying Mr Gates to his Land of Horrors, and so I devized a plan for cancelling my visit.

I came back to November 1762 and saw myself. I earnestly entreated myself not to attempt such a voyage – but the object of this entreaty was so intent on proving me a scoundrel and imposter than my arguments were in vain.

I had then but one chance left – to appear at the time and place in which my unsuspecting self was departing for the Future, and to stop myself, by force if need be. Gates and poor Jones had just climbed into the Time Machine when I materialized. They disappeared at the same moment, and the combined Force of our multiple Fluxions destroyed the machine utterly. It was the first and last of its kind. I believe.

For some reason I cannot determine, I am reversed. Mr Gates thought that perhaps each Time-Journey reversed all the atoms of one’s body. If you recall, when Gates first appeared, he kept trying to shake hands with his left hand. Likewise the coin in his pocket was backwards. In my journey to posterity, I was reversed. When I came back to speak to myself, I was put to rights again. Now I am again reversed.

You will not be able to include this in your book, I fear, unless as a Specimen of a madman’s raving, or as a silly Fiction. Let it be a Fiction, then, or ignore it, but do not deride me for a Lunatic.

For I have seen the Future; that is, I have peered into the pit of

Hell

.

I pray you remain constant to

Your friend,

Lemuel Jones

To Jeremy Botford, Esq.

Sept. 15

Dear Jerry,

I have not yet time to answer your letter properly. I trust Dr J. has sent you or will send you his Reminiscence. I may say he certainly acts peculiar nowadays. I understand his demeanour has declined steadily over the past ten years. Now he is often moody and distracted, or seemingly laughs at nothing.

For example, he burst out laughing today, when I asked him his opinion on American taxation. He is an enigma to

Your affectionate

Timothy Scunthe

Postscript. Your miniature lies, for I have just today looked on the original. My memory may be faulty but my eyes are keen. The wart is on the

right

.

Yours, &c.,

TT. Scunthe

HE

S

HORT

, H

APPY

W

IFE OF

M

ANSARD

E

LIOT

Mansard Eliot’s shadow, long with aristocracy, came out of his gallery on Fifth Avenue and moved along the sidewalk. Eliot knew exactly how he looked, with the sun gleaming in his hair. The hair would be parted slightly to one side, smoothed flat all over, and rich with dark, oily health. And the teeth: so white and even that Gladys said they reminded her of bathroom tiles.

Today he’d asked Gladys to become his wife. And if Dr Sky didn’t like it, so what? Dr Sky, with his ‘separation of dream life from reality’, his ‘horizontal cracks in the ego structure’! Let

him

try flopping down on the truth table like a seal pup and trying on the hard hat of memory … Mansard would, by Heaven, marry beneath his station.

Today she was making up her mind. While he waited, Mansard recalled the formula for locating street addresses on Fifth Avenue. From 775 to 1286, he knew, one dropped the last figure and subtracted 18. It was just something like that, he supposed, some geographical or historical fact, that had made him rich. So today he had asked Gladys to divorce her husband, Dean, who was unemployed. As soon as she answered ‘Yes’, Mansard would rush away to tell Dr Sky.

‘I can’t divorce Deanie,’ she whined. ‘It would break his back.’

‘I see.’ Mansard was grave. His cereal company had founded a sports foundation, whose director was just now clearing his throat to make an announcement. Mansard Eliot owned at least one tweed sports jacket, one black or navy blue blazer, one sterling shoehorn, one pair heavy slacks, one summer suit, one drip-dry shirt, one raincoat, one pair cotton slacks, two neckties, two sportshirts, one pair dress shoes, one pair canvas shoes, one light bathrobe, three pairs of socks, three sets of underwear, two handkerchiefs, one bathing suit, toilet and shaving articles (adapted for European use), and the building in which Gladys was a scrubwoman.

‘Deanie needs me,’ she explained. ‘People try to harm him. Yesterday I came home and found him sleeping on the couch, and the kids had put a plastic bag over his head. They hate his guts. He could have died. He hates their guts, too.’

What does Monique van Vooren do after dinner? A candle sputters. She fingers the bottle’s long, graceful neck. Suddenly there is a shower of liquid emeralds.

Mansard was taller than Gladys, who, of Gladys, Mansard and Dean, was not the shortest

.

‘He beats me,’ she explained. ‘He makes me have children I don’t want. He doesn’t want them either. He makes me go out and work, while he just lays around the house, guzzling two kinds of beer. My mother

hates his guts. She’ll be glad when I divorce him.’

The

Stallion

is a westernized shirt, extremely tapered, of cotton chambray. Why be bald?

‘Everyone just hates his guts,’ she explained. ‘He even hates himself. Only I understand and love and cherish him. Or maybe it’s only hate. Well, anyway, at least he loves his kids.’ Minnesota has 99 Long Lakes and 97 Mud Lakes.

‘Why don’t we just pick up and go to Europe?’ Mansard asked, glancing at himself in the lake. ‘Or somewhere else?’

‘Oh, I couldn’t leave the kids. They don’t get along with Deanie too well. They just don’t get along.’ Gladys put down her mop and pail and accepted a cigarette from the gold case he proffered. Satin sheets and pillow cases are a must for the compleat bachelor’s apartment. The Doggie Dunit makes an ideal gift memento or ‘ice-breaker’ at parties. So realistic your friends will gasp. Mansard’s hand trembled as he lit two cigarettes with a special lighter, then handed one to Gladys.

‘Do you smoke?’

‘Oh, no thanks. But you go ahead. I like the smell of a man’s cigarette.’

Exhaling a cloud of aromatic smoke, he said, ‘Let me think, now … ’

She lit two cigarettes and handed him one. When he had lighted their cigarettes, Mansard closed his eyes.

He consumed her with his eyes: her cold-reddened nose, print dress, feet swelling out of water-stained wedgies. His apartment, a penthouse over the supermarket, was filled each evening with soft Muzak. Alone at night, he’d listen, smoking one of his specially blended cigarettes in the dark. The apartment could take her for granted; why couldn’t he?