The Steel Wave (39 page)

Authors: Jeff Shaara

Scofield shook his head. “I know one of them came down in the water, sir. It landed right next to me. It’s buried deep.”

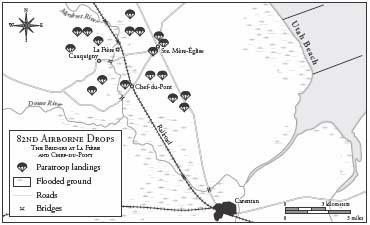

Gavin shook his head again, climbed up out of the trench, moved back to the embankment, sat. “We lost two of them right out here. One fell into the swamp about a mile to the north, and the Krauts have so many machine guns covering that ground, nobody could retrieve it. Another came down on dry ground in too many pieces. We reassembled the damned thing, only to find out the breechblock was missing. It’ll make some French farmer a nice yard ornament. So, no artillery support, and no radios to let anyone know what the hell we’re doing out here. And if that damned rumor about Utah Beach is accurate, we’re doing all this alone. Captain, see to your men. We’re going to move out toward Chef-du-Pont in a few minutes. I’ll give the word. Anybody bitches, tell them they might be glad they have those holes waiting for them if this little party goes to hell. Leave your sergeant with me for now.”

“Yes, sir.”

Scofield moved away, and Adams watched him through a fog, the hunger returning, dust in his mouth. He brushed dirt from the stinking stiffness of his uniform. “Sir, is there a canteen around here I could use? I lost my gear in the drop.”

Gavin pulled his own from his belt, handed it up to Adams. It was half full, and Adams took a brief swig, the water warm and perfect. He handed it back.

“What happened to your gear?” Gavin said.

Adams moved the last remnants of water around his mouth, the last swallow. “I came down in deep water. Had to cut myself free. But most of it left me in the air.” He wanted to say something about the pilot, the idiot Texan, but thought, No, let it go. There’ll be time for that jackass later.

Gavin searched the field. “Major! Get the sergeant here some rations. Whatever we have in that crate over there.”

“Sir, I can get it myself. No need to—”

“Sit down, Sergeant. I know you too well. You’re beat to hell, and you haven’t had a damned thing to eat. We did find a crate of C rations. Only good luck we had today. That’s a hell of a lot better than those damned K rations. Never figured out what deviled ham is anyway. But in the Cs, you can actually eat the beef stew. And the fruit cocktail’s not bad.”

The major hurried close, carrying a handful of small cans. He seemed nervous.

“Here you go, Sergeant. General, I wish you would stay down in the trench. The enemy artillery has been pretty consistent. They could begin again any time.”

“Worry about yourself, Major. Use my trench if you want. The sergeant here seemed to like it. But don’t get comfortable. We take that second bridge, I’ll need you to send word to General Ridgway. I expect somebody from his staff will be nosing out here pretty quick, once the shooting starts again. First, go find Captain Grayson. Tell him to pass word to the officers. We move out in ten minutes.”

Adams watched the major hurry away, dug into the beef stew with two fingers, then turned the can up and slurped the contents down his throat. He picked up a second can, hesitated, stuffed it into a pocket in his jacket. Yep, save that one for later. Gavin’s right about that deviled ham stuff. But right now it wouldn’t matter. Spam would work too. He noticed Gavin watching him, no smile, could see that Gavin was thinking, planning, his brain always working.

“This has been one hell of a mess, Sergeant. I’m not happy that all we’ve done is stir up the countryside and put our people on one bridge. Rommel’s too smart not to sort things out, and when he does, those bastards will be coming. If they had any idea how much confusion there is in these swamps and hedgerows, they’d have hit us already. I’m surprised as hell we haven’t had any Messerschmitts buzzing us. And I haven’t heard anything about Kraut armor yet, but it’s out there, and sooner or later it’s coming too. If we don’t get our people into a strong position by nightfall, we could get chewed up pretty badly.”

“Yes, sir.”

Gavin reached for a can of the rations and stared at it for a moment, rolling it in his hands. Adams felt a question brewing: If the bridges are close, we’re not that far from the designated drop zones.

“Sir, where did all that water come from? I saw the maps. The Merderet—”

“The Merderet is now spread out all over hell. Rommel opened the dikes, or the dam, or whatever the hell else he could do. I know those maps, Sergeant. Got one right here in my pocket. At La Fière Bridge, the river is supposed to be ten yards across. When we hit them this morning, we found out it was five hundred yards to the other side. The Krauts, or somebody, built a causeway on the far side of the bridge, to keep the road above water. The only thing I can figure is those idiots in the observation planes didn’t notice. They probably saw all that grassy swamp and assumed it was dry ground. They expected to see a narrow river, so that’s what they saw.” He looked at Adams with the hard stare Adams had seen before. “You lose some people?”

“Yes, sir. I tried like hell to figure a way to get to them. Where I came down, it was over my head. Lucky to have made it. Some weren’t. I think a few just…disappeared.”

Gavin looked down between his feet. “Sicily all over again, Sergeant. The pathfinders helped some, but you know how that goes. Some of them jumped into God-knows-where. At least, this time, there’s enough of us in one place. I’ve heard from other commands, officers gathering up scattered bunches, some organization here and there. There’s been a hell of fight around Sainte-Mère-Église, and that’s been going pretty well. Krause got himself wounded, and I think Vandervoort broke his leg on the jump, but General Ridgway’s close by, and I think he can handle things there for now. Our job right here is to take those two bridges and occupy the villages beyond. We’ve got half a day of daylight in front of us, and we’re going to do the best we can. There’s a pot load of glider troops coming in at dusk, which should help us out in a big way. They’ll be bringing in some artillery, for sure, jeeps, supplies, and ammo. Somebody sure as hell better have a radio.”

NEAR CHEF-DU-PONT BRIDGE

JUNE 6, 1944, 11 A.M.

Gavin led two hundred men toward the objective, and along the way they found others, more senior officers, battalion and company commanders, engineers, and bazooka carriers. They advanced in two columns, parallel to the river, the checkerboard of the hedgerow country providing protection from any distant observers. Adams stayed close to Scofield and was trailed closely by the men of his squad, those few familiar faces. It was the same throughout the advance, sergeants and field officers assembling their own men whenever possible, adding in those men who had been separated by the chaotic jump. Up front, Adams’s column was led by Lieutenant Colonel Edwin Ostberg, First Battalion commander of the 507th, another addition to Gavin’s growing army. Adams didn’t know Ostberg at all, but he had the same look as Gavin: no frills, no puffery, what every soldier needed a senior officer to be.

There had been shots from the direction of the other column, the sounds dispersed and muddled by the hedgerows, but it was all the reminder Adams needed that, in this blind maze, the enemy could be anywhere at all. He moved heavily, automatic steps, glancing continually into the hedgerow beside him. It was an uncomfortable habit, the thick brush too close, the fields beyond too obscured.

The men were moving off the roads, directed by Gavin toward a single railroad track, but the land around them had not changed; hedgerows still flanked the track. Adams glanced behind him, the men staying close, eyes nervous, silent, wary, everyone holding on to something inside, his own caution, fear, uneasiness. Adams looked to the front again, thought, At least we can’t get lost. Sure as hell, this track will lead to a town. Or a bridge. I guess the officers have that one figured out.

Adams saw Ostberg raise his arm, the order to halt. There were men emerging from the brush, coming out onto the track, one man cradling a BAR on his shoulder, another man with a sergeant’s stripes. Adams saw machine guns, more troopers dug in close to a thick row of brush, a long narrow trench.

Beside him, Scofield said, “I better see what’s up. We must be close.”

The captain moved up, joining the conversation, low voices Adams couldn’t hear. But the talk was brief, arms pointed forward, and Ostberg looked back toward the column, a quiet stare, seeming to measure the men behind him. Adams heard quick footsteps, boots on gravel, Gavin jogging past him, moving to the front, more talk, and then Scofield came back toward him, his face red, alive.

“The village is up ahead, a half mile. The Krauts are there for sure, machine-gun nests at least. There are a few houses, so snipers could be anywhere. We’re going to spread out, push in, and blast the bastards.” Scofield was breathing heavily, put a hand on Adams’s arm.

“You ready to go to work?”

Adams felt a strange quiver in his legs, ignored it, focused on the icy burn in his stomach. “Sure.”

There was nothing else to say, numb acceptance. He looked behind him, saw Marley, a helmet now, someone else’s M-1 held tightly across his chest. Marley made a sharp nod toward him, wide-eyed, anxious. Beside him was Unger, a dirty-faced boy, and Adams stared past, wouldn’t see the boy’s eyes, didn’t want to know if Unger was scared. Of course he’s scared. We’re all scared. Even…me. Dammit, knock that off.

The others were spread out all around the track, officers moving quietly through them, passing the word, and Adams tried to feel the excitement, fought the strange numbness in his brain, the quiver still there. He looked at the Thompson, the short barrel a dull sheen of oil and dirt, his hands dirtier still. The large pocket on his pants leg was still heavy, four magazines for the submachine gun, four grenades still clipped to his jacket. He pushed at the gloom in his head, angry now. Dammit, you’ve got a job to do! He tried to pull energy—confidence—from the faces of the others, even from men who had never done this before. But there was just as much fear there, men pulling their rifles close, silent, some staring out past him, toward Ostberg and beyond, trying to see what was not yet there: the enemy, waiting.

Adams hoisted the Thompson in close, tucked the butt under one arm, and turned to Scofield again, the captain still looking at him, and Scofield said, “Let’s get those sons of bitches.”

T

hey crept low, using the brush for cover, but the trees ended, the ditches alongside the railroad tracks more shallow. Down the road, Adams saw the first house, small and fat, one window. Across the road, the men had more cover, and he glanced that way, saw Scofield, Unger, another twenty men in line, all crawling, silent, the slow stalk of a dangerous beast. Adams stayed close beside the mound of the railroad track, the ribbon of steel just enough to shield his helmet. He stopped, lying flat now, nursed the pains in his knees, raised his head slightly, and stared at the single window, a small black square, searching for any movement. The house was more than two hundred yards away, but the troopers were mostly in the open, in plain view of any machine gunner who might be inside. Adams heard puffs of breathing behind him, from others spread along the track, and thought, We’re sitting ducks. But nobody’s shooting at us. Where the hell are they? We need to get up and move, or…what? Artillery? Yeah, that would be nice. Blow that house to hell.

The noise was sudden, a hard blowing cough, and Adams dropped his head, his face in the rocks of the track bed. But the sound grew, more quick coughs. He looked ahead to a column of black smoke rising from the village, heard the roar of an engine. He felt the vibration in the rocks beneath him, and saw the train now, coming out from the village, the engine moving slowly. He felt himself pulling backward, oh, hell, and behind him, men were spreading out away from the tracks, the train coming toward them. He glanced that way, but his legs wouldn’t move, the low rumble in the ground holding him. The rifle fire came now, shouts on the far side of the track, a burst from a Thompson. Adams slid his submachine gun forward, aimed, nothing but the green steel of the train engine, heard new sounds, shots from the train, splatters on the rocks, the pops of rifles. He held his fire, nothing to shoot, but the men around him had spread out, some flat in short grass, firing, the train a hundred yards away, still moving slowly toward them, and now, with a great groan of squealing brakes, it stopped. The firing continued, and Adams saw German uniforms, a flood of men leaping from the train, one man falling, the others running. He pulled the Thompson against his shoulder, but the uniforms were out of sight, his brain yelling, Don’t waste ammo! From both sides of the tracks, the firing continued, by men who could see past the train, who had targets.

Adams felt the fury and frustration, nothing to shoot at. Men were up and moving, one voice, Gavin: “They’re retreating! Get to the train!”

The train belched a great plume of smoke and, with a high groan of steel on steel, began to move backward, its own lumbering retreat. Adams pulled himself up, was running with the others, more Germans leaping down from the train, frantic, scampering away, some shot down, pops of fire out to one side. The Americans were at the train now, some climbing up, sprays of fire, the train stopping again. Adams was beside the engine, the Thompson pointed forward, still no targets, just flickers of gray, the Germans pulling back farther, disappearing deep into the village. The shooting stopped. Adams heard a cheer, loud curses, and kept his stare on the village, the small windows, his hands shaking, the tracks now swarming with Americans. And close beside him, the voice of Gavin.