The Story of Ireland: A History of the Irish People (38 page)

Read The Story of Ireland: A History of the Irish People Online

Authors: Neil Hegarty

Tags: #Non-Fiction

By 1896, Connolly had moved to Dublin with his expanding family in order to pursue this agenda. A socialist republic was his aim, but Ireland presented very different challenges: the rising tide of cultural nationalism and the clamour for Home Rule inevitably absorbed much of the available political energy. Nevertheless, Connolly began the process of disseminating his class-based message in the city via a series of pamphlets and publications and in street-based demonstrations. He was loud in his dismissal of Home Rule as a political solution: ‘England would still rule you,’ he wrote. ‘She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through her usurers, through the whole array of commercial and individualistic institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and blood of our martyrs. England would rule you to your ruin…’

7

An agent sent by the authorities at Dublin Castle to listen to one of Connolly’s public speeches dismissed it as ‘the usual twaddle’ – although the fact that the authorities considered him worth listening to in the first place indicates that he had managed to carve out something of a niche for himself.

8

He was a nationalist in the sense that his socialist republic would be founded on the Irish nation; indeed, he had always been prepared to ally himself with explicitly nationalist causes. He was arrested, for example, at the demonstration against Chamberlain’s honorary doctorate from Trinity College Dublin in December 1899, and was in general active in the cause of the Boers. Socialism, however, remained key to his political message – and the limitations of this message in an Irish context were all too evident. In general terms Connolly addressed himself neither to cultural nationalists, nor to the mass of the rural poor, nor to the country’s Catholic middling classes. In the process, he ended any prospect of widespread popular backing.

From 1903 he spent seven years in the United States, organizing, lecturing and observing the labour movement at first hand; three more were passed in Belfast, where class politics still struggled to be heard amid the city’s prevailing bitter sectarianism. In the summer of 1913, however, industrial unrest in Dublin brought Connolly south once more. Confrontation between workers and employers had become a dominant feature of economic life: the ITGWU had rapidly increased in membership and influence and had gradually won concessions from a variety of employers. Larkin now felt secure enough to challenge Dublin’s most powerful employer: William Martin Murphy, a former nationalist MP and the present owner of the

Irish Independent

and

Irish Catholic

newspapers, Clery’s department store in central Dublin and much of the city’s tram network. On 15 August Murphy had ‘locked out’ union members from their jobs in the

Irish Independent

building; Larkin called a strike, Murphy extended the lock-out – and by early September, matters had escalated into an all-out confrontation.

The lockout was marked by a good deal of violence: the workers were threatened by attack from both the police and a series of employer-backed vigilante groups, and in response Connolly organized a protective group, the Irish Citizen Army (ICA). Ultimately, some twenty-five thousand workers were locked out and deprived of a regular wage: this in turn, because they had families, meant that close to one hundred thousand people were threatened with penury and hunger. A relief fund brought a degree of respite, but by the end of January 1914 the ITGWU was forced to admit defeat. The union members gradually returned to work, on terms drawn up by the employers, shortly after the end of the lock-out. Meanwhile, the Catholic bishops condemned socialism, thus leaving no room for doubt as to the attitude of the Church.

Connolly’s speeches to the workers during the lock-out had led to his arrest and imprisonment, and he had briefly gone on hunger strike. Now, with the defeat of the workers in the spring of 1914, he was forced into a reassessment of his political views. The events of the lock-out reinforced his sense that labour needed more than ever to organize, the better to withstand its capitalist enemies; in addition, he devoted much energy to expanding and training the ICA as a front line of defence. At the same time, however, the failure of the lock-out undermined his class-based vision of Ireland’s future, while the notion of a united socialist Ireland seemed as remote as ever. It was clear to him that the war now approaching in Europe might present a golden opportunity – and clear too that nationalist and not socialist politics might prove the best vehicle for bringing about change.

Amid this plethora of activism, constitutional politics had certainly not become irrelevant. By 1910, for example, parliamentary reform had once again brought the possibility of a form of Irish political autonomy, the old goal of Home Rule, within reach. In that year, the delicately reunited Irish Party at Westminster supported the formation of a new Liberal government under Herbert Asquith – on the clear understanding that a Parliament Act would be passed, enabling the veto of the Conservative-dominated Lords to be overridden for the first time by the Commons. This was reform fundamental to the very institution of parliament itself – and it was indeed passed, with a third Home Rule bill swiftly proposed in the spring of 1912.

In truth this was a modest enough measure, repatriating to Dublin authority many domestic issues but retaining at Westminster control over Irish foreign policy, taxation and military affairs. Yet it was a bill that this time stood a very good chance of passing both the Commons and the Lords and becoming law. In Belfast the Ulster Unionists mustered in opposition, the fault lines in Ireland opening now into chasms. In September 1912 Sir Edward Carson led 250,000 Ulstermen in signing the Covenant, a declaration of intent to use ‘all means which may be found necessary’ to resist Irish self-government. Ulsterwomen had another, rather less martial Declaration, that noted ‘our desire to associate ourselves with the men of Ulster’ in their opposition to Home Rule. And in London, the Conservative opposition declared its support for the Unionists: ‘I can imagine no length of resistance to which Ulster will go,’ noted their leader Andrew Bonar Law, ‘in which they will not be supported by the overwhelming majority of the British people.’

9

Ulster Unionism was an articulate and daunting political force. It was unified by fear – and yet it was essentially no more homogeneous an entity than was Irish nationalism. For there was more to the Protestant population of Ulster than the prosperous mercantile elite of Belfast and its hinterland: it also embraced a class of small farmers scattered throughout the province, the remnants of the Anglican Ascendancy, and the tens of thousands of employees of Belfast’s shipyards and factories. The harsh by-products of Belfast’s industrial class, meanwhile, were evident for all to see in the forms of heavy reliance upon child labour, minimal levels of welfare, widespread poverty and general social distress. Class, in other words, was as intrinsic an aspect of life in Ulster as it was in other developed societies. Yet – as Connolly had discovered – such divisions and internal tensions could be papered over in the face of Home Rule, to be replaced by the imperatives of religion and race.

In these years leading up to World War I, Unionist political leaders engaged in the slow process of securing the extrication of Ulster, or a section of the province, from any new constitutional arrangement. The partition of the country, which had first emerged as an issue in the aftermath of the first Home Rule bill two decades previously, was now live and pressing; however, nobody could as yet determine whether partition would in fact happen, much less what final shape it might take. It was also an issue riddled with contradiction: the Home Rule that Unionists had rallied to prevent in the closing decades of the nineteenth century was now acceptable to them – if only Ulster could be removed from the equation.

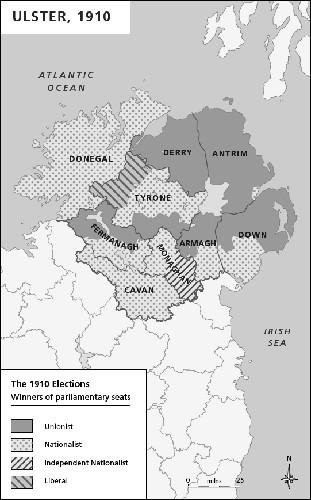

Underlying these political calculations was a cold numbers game. According to the 1911 census, the Protestant population of the province of Ulster was just under 900,000, the Catholic population just under 700,000. This was too slender a demographic majority for comfort, especially when a generally higher Catholic birth rate was taken into account. Unionist leaders envisaged an Ulster in which Protestants would form a permanent political elite: one consisting of counties Antrim and Down (with hefty Protestant majorities), and Derry and Armagh (with small Protestant majorities); Fermanagh and Tyrone (with no Protestant majorities at all, although Protestants held the greater part of the land) would be added to bring a sense of critical mass to the new order. The three remaining Ulster counties with their substantial Catholic majorities, however, would not be included. Unionist leaders were thus open to the charge that they were on the one hand deploying the argument of democratic imperatives, while simultaneously denying the justice of that same argument. They could also be accused of abandoning their Unionist brethren in Cavan, Monaghan and Donegal to their fate, in the interests of

realpolitik

.

The Home Rule bill passed a third reading in the Commons in January 1913. In the same month, the Ulster Volunteers were created as a resistance militia; rapidly, its membership climbed to over ninety thousand. The force was daunting and professional: it included many highly trained former members of the British army, and soon it had diversified into women’s auxiliary units and the paraphernalia of a regular army. Its creation led inevitably to the formation of a rival force: the Irish Volunteers, the inaugural meeting of which took place in November 1913 amid the bourgeois surroundings of Wynn’s Hotel in central Dublin, a few doors along from the Abbey. Redmond’s Irish Party had a stake in this new organization – figures in the party sat on its council – but so too did the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), reconstituted from the Fenian period and consisting of individuals who had nothing but disdain for the forces of constitutional nationalism as embodied in Redmond and his Westminster colleagues. Soon, the IRB membership was working discreetly to radicalize the politics of the new movement.

These IRB members consisted of older Fenian figures – for example, Tom Clarke, who had spent years in prison for his involvement in bomb attacks in England – together with younger, highly educated and energetically committed activists. Among these were Joseph Plunkett, a well-travelled scholar of Irish and Esperanto; Thomas MacDonagh, also an Irish scholar and a trade unionist; and Patrick Pearse, a poet, intellectual, barrister and founder of a school in Dublin dedicated to the revival of the Irish language. Pearse’s cultural nationalism was influenced in part by the romantic mythology of Gaelic Ireland – yet he was a pragmatist too: of the rising Unionist military organization in Ulster he noted bluntly that ‘an Orangeman with a rifle [is] a much less ridiculous figure than the nationalist without a rifle’.

10

A key aspect of Pearse’s political ideology was ‘blood sacrifice’, the Christian-inflected concept prevalent in Europe at this time that war might help to cleanse and renew a nation. ‘When war comes to Ireland,’ he wrote during World War I, ‘she must welcome it as she would the angel of God. And she will.’

11

The sense of a rising threat to public order was reflected in the government’s tentative proposal, in March 1914, to send army divisions to Ulster in order to face down any potential threat. This plan came to nothing, however, in the face of a proto-mutiny at the Curragh barracks, west of Dublin, in which scores of cavalry officers threatened to resign if ordered north. The episode amply demonstrated the range of Ulster Unionist support – and now tension was ratcheted up yet further as each of the rival militias armed itself, beginning in the small hours of 25 April when members of the Ulster Volunteers unloaded several hundred tonnes of German-manufactured guns and munitions at Bangor, Larne and Donaghadee harbours and distributed them with smooth efficiency across the province.

In response – and with the assistance of Sir Roger Casement, an Irish-born former British diplomat who had gravitated towards the Irish nationalist cause – the Irish Volunteers too procured weapons from Germany: in July, the yacht

Asgard

sailed into the harbour at Howth, north of Dublin, and unloaded its (rather smaller) cargo of munitions in broad daylight.

*

The arms were taken into the city for distribution; an army detachment belatedly sent out to intervene fired into a crowd of jeering Dubliners later that day, killing four; the event was captured by the painter Jack B. Yeats in

Batchelor’s Walk, In Memory

(1915), which portrays a woman laying flowers at the scene of the killings. Ireland appeared indeed to be on the edge of widespread civil unrest – and for the British authorities, a kaleidoscope of other problems was already looming: imprisoned suffragettes were on hunger strike; a general strike was threatened; and Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austrian throne, had been assassinated at Sarajevo in June. It seemed clear that, by summer’s end, Europe would be on fire.