The Story of My Face

THE STORY

of

MY FACE

Kathy Page was born in London but is currently living on the west coast of Canada with her husband and two young children. Her fifth novel,

The Story of My Face

, was long-listed for the Orange Prize in 2002. She has worked as a writer in residence at a variety of universities and in other settings, including a Norfolk fishing village and, in 1992, a men's prison in the UK. Her website can be visited at

www.KathyPage.info

.

By Kathy Page

Back in the First Person

The Unborn Dreams of Clara Riley

Island Paradise

Frankie Styne and the Silver Man

As in Music

The Story of My Face

Alphabet

The Find

THE STORY

of

MY FACE

Kathy Page

McArthur & Company

Toronto

Copyright © 2002 Kathy Page

All rights reserved.

The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, without the express written consent of the publisher, is an infringement of the copyright law.

First published in 2002 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

This edition published in Canada in 2011 by

McArthur & Company

322 King Street West, Suite 402

Toronto, ON M5V 1J2

www.mcarthur-co.com

L

IBRARY AND

A

RCHIVES

C

ANADA

C

ATALOGUING IN

P

UBLICATION

Page, Kathy, 1958-

The story of my face / Kathy Page.

ISBN 978-1-55278-995-7

I. Title.

PR6066.A325S76 2011Â Â Â Â 823'.914Â Â Â Â C2011-900909-9

eISBN 978-1-77087-118-2

The publisher would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for our publishing activities. The publisher further wishes to acknowledge the financial support of the Ontario Arts Council and the OMDC for our publishing program.

Typesetting by Deltatype Ltd

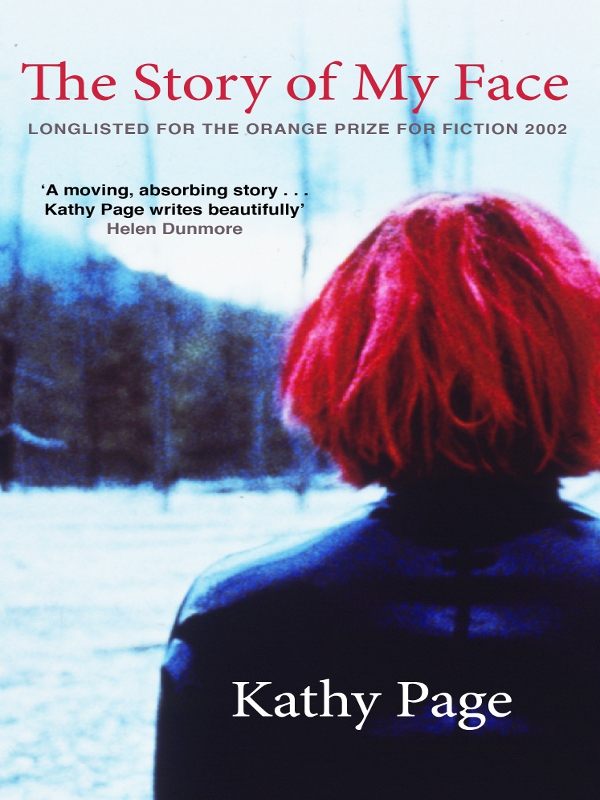

Cover image © Tony Stone

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath or that is in the water under the earth . . .

(Exodus 20:4)

Contents

I look up from the map and see a tall woman in a padded coat, standing about two metres from the car, staring in at me. Her shopping bags are on the ground, but her arms hang straight down at her sides as if she were still carrying something heavy. She stares hard. I don't like it, but the fact is I am a complete stranger in this unpronounceable speck of a place, Elojoki, that seems to have been dropped in the middle of flat and freezing nowhere, roughly 200 kilometres south of the Arctic Circle. There are four shops, one road, a scattering of low-rise buildings, high winds, ice and conifers for miles. It would be odd if I didn't attract attention. Besides, I have spent the last twenty-five years learning how to cope with stares. I can catch a stare lightly and turn it into a smile or the beginning of a conversation; also, I can push it back hard enough to hurt â

But this woman goes on and on staring even when she sees I am looking straight back at her and it's clear to me now that this is not a simple, curious stare. It's as if she is trying to do something to me, to make something happen, just by looking. Her jaw is slack and the whole of her face has gathered around her eyes. I could just drive on, but something makes me want to break the stare before I go. So I wind down my window, smile, point ahead and ask, even though I already know:

âIs the church this way?' My voice is bright and ordinary, slow, but competent in its handling of the foreign sounds; my breath billows and sinks heavily in the air between us. The woman neither replies nor moves. I abandon Finnish, try Swedish. Finally, I shrug, open my hands, and set off on the last few hundred metres of my journey. The woman, I see in the mirror, has turned around and is still watching me.

Elojoki has a history. That's why I'm here, so I'm going to need to make allowances. But right now I'm just too tired to do so. A delayed flight, the drive â the last hour of it the worst: mile after mile of narrow, icy road hugging the course of a frozen river â the trees to either side a green so dark they might as well be black. And now the staring woman. Right now, the whole trip, which I've worked towards for years, seems ludicrous: a woman of forty-four, not married, nor even attached, searching for a long-dead man. In Elojoki.

Yet here I am. Just to the other side of the bridge is the church, set on boulder-strewn ground a few feet higher than the rest. It is squat, wood-built and ship-lapped, painted grey-blue with a shingled roof and a small spire. Seeing it â its foreignness, the fact that it has survived â lifts my mood a little. Beyond it is a bell tower, the cemetery. To the right, behind a thicket of leafless birch trees, is the

pappila

, the long, atticked house that came with the pastor's job. It's empty now. Somewhere behind that, I guess, is the smaller guest-house where Tuomas Envall lived when he first arrived here, and where, by sheer luck in the timing of my application, I am going to live too. All I have to do in return is give a public lecture on my findings before I depart.

Heikki Seppä, a tall man with a slight stoop, emerges from a jeep parked outside the

pappila

. His official title is Local Officer for the National Board of Antiquities, Department of Historic Buildings and Sites, but since we met last year when the arrangements were being made, there is, mercifully, no need for introductions. A quick handshake, then he takes the rucksack and book-box and leads the way, warning of slippery patches on the path.

The house is just one room, lined and floored in wood. There's an old-fashioned wood-burning stove. Triple-glazed windows look out in three directions. A large table sits in the middle of the space. There is also a rather short-looking wooden bed, a rug and a cupboard and dresser, both old. The kitchen area and sink are under the east-facing window; a table-top fridge, a microwave and a vast, white plastic and glass coffee-maker have been brought in. Plumbing, new windows, background heating and electricity, along with the bathroom extension at the back, Heikki explains, were added quite recently. The Envallist rift with the official church was widening, and funds to update the

pappila

were not forthcoming, so the pastor moved in here just before he left altogether. Next year, when restoration begins, these modernisations will all be stripped out, and the corrugated roof will be replaced with authentic shingles. âSo you are just in time!' he tells me.

It is very important for me not to attempt to use the stove and not to smoke in this house, nor allow anyone else to â he speaks in English, slowly, almost perfectly, making the sentences first in his head. As he speaks, he opens and shuts the doors of cupboards, fridge, microwave, glancing inside each, then closing them again, seeming pleased at their emptiness. He takes me in with small, easily bearable glances.

I tell him, I don't smoke and certainly won't let anyone else do so.

He hopes I will be warm enough, and not too lonely in a quiet, out-of-the-way place such as this.

âThe house is perfect,' I tell him. âI am so very grateful for the opportunity to be here, to read the records and talk to contemporary villagers about the stories and memories handed down to them, to study their beliefs, that even if there were discomfort involved, it wouldn't bother me at all. As it is, I could not ask for more â'

âGood,' he says, running his hand over grey-blond hair that is thinning and cut short, âI'll leave you to it.' He makes for the door, remembering at the last moment to give me the key.

When we shake hands again â this time without our gloves â I notice how large his are and that the little finger on his left is missing, which I didn't notice before. A tiny connection between us, a physical similarity. A good sign, perhaps.

Later, showered, wearing my dressing-gown and slippers, I make coffee, sit down at the spruce table (which is contemporaneous with Tuomas Envall, but, according to Heikki Seppä , not original) and stare out through the north-facing window. The evening is somehow bluer than at home.

I think in an idle, disconnected way of the years of work that have brought me here. First the languages, acquired night after night in the language lab, progressing rather as does a climber on sheer rock, inching up with crampons and ropes. Then research, contacts, grant applications, the sabbatical year, the laptop, maps. I have a brief, vivid picture of my office as it was before I packed â the books on the shelves, the maroon chairs with foam sticking out from the cushion seams, the sun coming in through broken Venetian blinds â and then I think of my least and most favourite students. After all, it's only three days since I cleared out my papers and books. That afternoon, I had my party, with colleagues and their partners and a fulsome speech from the Dean. Daffodils were in bloom, the grass was bright green.

Now, I'm thoroughly elsewhere, and I don't think I shall miss getting my slides in order or holding forth about Religion and Society, The Idea of God, The Paradoxes of Belief and so on. I turn off the desk lamp, switch on another by the bed, and close the three pairs of plaid curtains. The bed is just my length, and agreeably soft. I stretch out on top to begin with, aware that I promised to phone my mother and also that I should clean my teeth before I let myself sleep. The blue between the trees drifts into black, and silence sings around me. Perhaps half an hour later I'm still there, staring at the ceiling in a pleasant state of suspended animation, when there's knocking at the door â tentative, but still quite loud enough to make me jump out of my skin. Then it grows louder and urgent. I find myself standing behind the door (which doesn't have a chain), my heart racing as I watch it shake in the frame. I'm more or less paralysed, completely unable to find the right words in either language â