The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (19 page)

The news of Cæsar's crossing the Alps at the head of his army filled the senators with dismay. They feared the anger of a man who had won so many victories. Remembering that Pompey had often saved the state from threatening dangers, they implored him to take an army and go northward to check Cæsar's advance.

As we have already seen, Cæsar did not like bloodshed; and he was unwilling to fight with other Romans if he could secure what he wished without doing so. He therefore paused several times, and made several attempts to make peace with Pompey. But, when all his offers were refused, he ceased to hesitate, and boldly crossed the Rubicon, crying, "The die is cast!"

The Rubicon was a small river which flowed between the province of Gaul and the territory of the Roman republic. For this reason, it was against the law for the governor of Gaul to cross it without laying down his arms. As Cæsar did not obey this law, he plainly showed that he no longer intended to respect the senate's wishes, and was ready to make civil war.

Cæsar's crossing of the Rubicon was a very noted event. Ever since then, whenever a bold decision has been made, or a step taken which cannot be recalled, people have exclaimed: "The die is cast!" or "He has crossed the Rubicon!" and, when you hear these expressions used, you must always remember Cæsar and his bold resolve.

When Pompey heard that Cæsar had invaded Roman territory, and was coming toward Rome, his heart was filled with terror. Instead of remaining at his post, he fled to the sea, and embarked at Brundisium, the modern Brindisi. His aim was to sail over to Greece, where he intended to collect an army large enough to meet his rival and former friend.

Cæsar marched into Rome without meeting with any opposition. Arrived there, he broke open the treasury of the republic, and took all the money he needed to pay his troops. Then he sent out troops to meet Pompey, while he went straight to Spain, where he added to his fame by conquering the whole country in a very short time.

The conquest of Spain completed, the untiring Cæsar next set out for Greece, where he planned to meet Pompey himself. In the mean while, however, Pompey had gathered together many troops, and had been joined by many prominent Romans, among whom were Cicero, the great orator, and Brutus, a severe and silent but very patriotic man.

The Battle of Pharsalia

W

HEN

Cæsar reached the port of Brundisium he found that there were not vessels enough to carry all his army across the sea. He therefore set out with one part, leaving the other at Brundisium, under the command of his friend Mark Antony, who had orders to follow him as quickly as possible.

Instead of obeying promptly, Mark Antony waited so long that Cæsar secretly embarked on a fisherman's vessel to return to Italy and find out the cause of the delay. This boat was a small open craft, and when a tempest arose the fishermen wanted to turn back.

Cæsar then tried to persuade them to sail on, and proudly said: "Go on boldly, and fear nothing, for you bear Cæsar and his fortunes." The men would willingly have obeyed the great man, but the tempest soon broke out with such fury that they were forced to return to the port whence they had sailed.

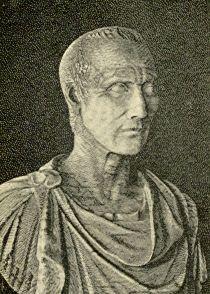

Bust of Cæsar

Shortly after this, Mark Antony made up his mind to cross the sea, and joined Cæsar, who was then besieging Pompey in the town of Dyrrachium, in Illyria. To drive the enemy away as soon as possible, Pompey had destroyed all the provisions in the neighborhood. Cæsar's men suffered from hunger, but they were too loyal to desert him. To convince Pompey that the means he had used were of no avail, they flung their few remaining loaves into the enemy's camp, shouting that they would live on grass rather than give up their purpose.

Cæsar, however, saw that his men were growing ill for want of proper food, so he led them away from Dyrrachium into Thessaly, where they found plenty to eat, and where Pompey pursued them. Here, on the plain of Pharsalia, the two greatest Roman generals at last met in a pitched battle; and Pompey was so sure of winning the victory that he bade the soldiers make ready a great feast, which they would enjoy as soon as the fight was over.

Pompey's soldiers were mostly young nobles, proud of their fine armor and good looks, while Cæsar's were hardened veterans, who had followed him all through his long career of almost constant warfare. Cæsar, aware of the vanity of the Roman youths, bade his men aim their blows at the enemies' faces, and to seek to disfigure rather than to disable the foe.

The battle began and raged with great fury. Faithful to their general's orders, Cæsar's troops aimed their weapons at the faces of their foes, who fled rather than be disfigured for life. Pompey soon saw that the battle was lost, and fled in disguise, while Cæsar's men greatly enjoyed the rich banquet which their foes had prepared.

Unlike the other Romans of his time, Cæsar was always generous to the vanquished. He therefore soon set free all the prisoners he had made at Pharsalia. Then, instead of prying into Pompey's papers, as a mean man would have done, he burned them all without even glancing at them. This mercy and honesty pleased Brutus so greatly that he became Cæsar's firm friend.

Pompey, in the mean while, was fleeing to the sea. He had been surnamed the Great on account of his many victories; but the defeat at Pharsalia was so crushing that he was afraid to stay in Greece. He therefore embarked with his new wife, Cornelia, and with his son Sextus, upon a vessel bound for Egypt.

As he intended to ask the aid and protection of Ptolemy XII., the Egyptian king, he composed an eloquent speech while on the way to Africa. The vessel finally came to anchor at a short distance from the shore, and Pompey embarked alone on the little boat in which he was to land.

Cornelia staid on the deck of the large vessel, anxiously watching her husband's departure. Imagine her horror, therefore, when she saw him murdered, as soon as he had set one foot ashore. The crime was committed by the messengers of the cowardly Egyptian king, who hoped to win Cæsar's favor by killing his rival.

Pompey's head was cut off, to be offered as a present to Cæsar, who was expected in Egypt also. The body would have remained on the shore, unburied, but for the care of a freedman. This faithful attendant collected driftwood, and sorrowfully built a funeral pyre, upon which his beloved master's remains were burned.

The Death of Caesar

A

S

soon as Cæsar landed in Egypt, he was offered Pompey's head. Instead of rejoicing at the sight of this ghastly token, he burst into tears. Then, taking advantage of his power, he interfered in the affairs of Egypt, and gave the throne to Cleopatra, the king's sister, who was the most beautiful woman of her time.

This did not please some of the Egyptians, who still wished to be ruled by Ptolemy. The result was a war between Ptolemy and the Egyptians on one side, and Cæsar and Cleopatra on the other.

In the course of this conflict the whole world suffered a great loss; for the magnificent library at Alexandria, containing four hundred thousand manuscript volumes, was accidentally set on fire. These precious books were written on parchment, or on a sort of bark called papyrus. They were all burned up, and thus were lost the records of the work of many ancient students.

Cæsar was victorious, as usual, and Cleopatra was made queen of Egypt. The Roman general then left her and went to fight in Pontus, where a new war had broken out. Such was the energy which Cæsar showed that he soon conquered the whole country. The news of his victory was sent to Rome in three Latin words,

"Veni, vidi, vici,

" which mean, "I came, I saw, I conquered."

After a short campaign in Africa, Cæsar returned to Rome, where he was rewarded by four triumphs such as had never yet been seen. Not long afterwards, he was given the title of Imperator, a word which later came to mean "emperor." In his honor, too, one of the Roman months was called Julius, from which our name July has come.

Cæsar made one more remarkable campaign in Spain before he really settled down at Rome. He now devoted his clear mind and great energy to making better laws. He gave grain to the hungry people, granted lands to the soldiers who had fought so bravely, and became ruler under the title of dictator, which he was to retain for ten years.

As the people in Rome were always very fond of shows, Cæsar often amused them by sham battles. Sometimes, even, he would change the arena into a vast pool, by turning aside the waters of the Tiber; and then galleys sailed into the circus, where sham naval battles were fought under the eyes of the delighted spectators. He also permitted fights by gladiators; but, as he was not cruel by nature, he was careful not to let them grow too fierce.

Cæsar was a very ambitious man, and his dearest wish was always to be first, even in Rome. Some of his friends approved greatly of his ambition, and would have liked to make him king. But others were anxious to keep the republic, and feared that he was going to overthrow it.

Among the stanch Roman republicans were Cassius and Brutus. They were friends of Cæsar, but they did not like his thirst for power. Indeed, they soon grew so afraid lest he should accept the crown that they made a plot to murder him.

In spite of many warnings, Cæsar went to the senate on the day appointed by Cassius and Brutus for his death. It is said that he also paid no attention to the appearance of a comet, which the ancient Romans thought to be a sign of evil, although, as you know, a comet is as natural as a star. Cæsar was standing at the foot of Pompey's statue, calmly reading a petition which had been handed to him. All at once the signal was given, and the first blow struck. The great man first tried to defend himself, but when he saw Brutus pressing forward, dagger in hand, he sorrowfully cried: "And you, too, Brutus!" Then he covered his face with his robe, and soon fell, pierced with twenty-three mortal wounds.

Death of Cæsar

Thus Cæsar died, when he was only fifty-five years of age. He was the greatest general, the best statesman, and the finest historian of his time and race. You will find many interesting things to read about him, and among them is a beautiful play by Shakespeare.

In this play the great poet tells us how Cæsar was warned, and how he went to the senate in spite of the warnings; and then he describes the heroic death of Cæsar, who was more grieved by his friends' treachery than by the ingratitude of the Romans whom he had served for so many years.

The Second Triumvirate

C

AESAR

,

the greatest man in Roman history, was dead. He had been killed by Brutus, "an honorable man," who fancied it was his duty to rid his country of a man whose ambition was so great that it might become hurtful.

Brutus was as stern as patriotic, and did not consider it wrong to take a man's life for the good of the country. He therefore did not hesitate to address the senate, and to try and explain his reasons for what he had done.

But to his surprise and indignation, he soon found himself speaking to empty benches. The senators had all slipped away, one by one, because they were doubtful how the people would take the news of their idol's death.

Brutus, Cassius, and the other conspirators were equally uncertain, so they retired to the Capitol, where they could defend themselves if need be. The Romans, however, were at first too stunned to do anything. The senators came together on the next day to decide whether Cæsar had really been a tyrant, and had deserved death; but Cicero advised them to leave the matter unsettled.

Thus, by Cicero's advice, the murderers were neither rewarded nor punished; but a public funeral was decreed for the dead hero. His remains were exposed in the Forum, where he was laid in state on an ivory bed. There Cæsar's will was read aloud, and when the assembled people heard that he had left his gardens for public use, and had directed that a certain sum of money should be paid to every poor man, their grief at his loss became more apparent than ever.

As Cæsar had no son, the bulk of his property was left to his nephew and adopted son, Octavius. When the will had been read, Mark Antony, Cæsar's friend, pronounced the funeral oration, and made use of his eloquence to stir up the people to avenge the murder.