Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

The Success and Failure of Picasso (33 page)

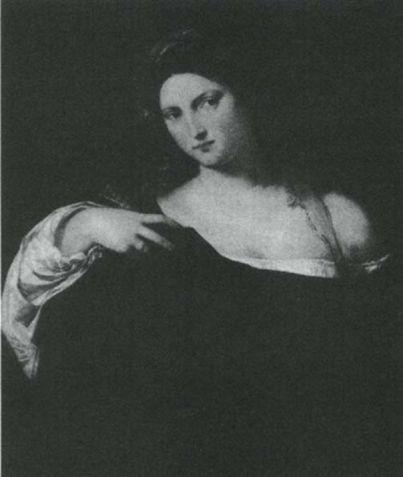

Yet just as the nipple is only part of the body, so its disclosure is only part of the painting. The painting is also the woman’s distant expression, the far-from-distant gesture of her hands, her diaphanous clothes, her pearls, her coiffure, her hair undone on the nape of the neck, the flesh-coloured wall or curtain behind her, and, everywhere, the play between greens and pinks so beloved of the Venetians. With all these elements, the painted woman seduces us with the visible means of the living one. The two are accomplices in the same visual coquetry.

121

Tintoretto. Woman with Bare Breasts.

Tintoretto was so called because his father was a dyer of cloth. The son, though at one degree removed and hence within the realm of art, was, like every painter, a ‘colourer’ of bodies, of skin, of limbs.

Supposing that beside the Tintoretto, we now put

Giorgione’s

Old Woman

, painted about half a century earlier. The two works together show that the intimate and unique relation existing between pigment and flesh does not necessarily mean sexual provocation. On the contrary, the theme of the Giorgione is the loss of the power to provoke.

122

Giorgione. Old Woman. c. 1969

I met the Bishop on the road

And much said he and I.

‘Those breasts are flat and fallen now,

Those veins must soon be dry;

Live in a heavenly mansion,

Not in some foul sty.’

‘Fair and foul are near of kin,

And fair needs foul,’ I cried.

Yet no description in words – not even Yeats’s lines – can register as this painting does the sadness of the flesh of the old woman whose right hand makes a similar but so different gesture. Why? Because the pigment has become that flesh? This is almost true but not quite. Rather, because the pigment has become the communication of that flesh, its lament.

Finally, let us add to the other two paintings

Titian’s

Vanity of the World

, in which a woman has abandoned all her jewelry (except a wedding ring) and all adornment. The ‘fripperies’ which she has discarded as vanity are reflected in the dark mirror she holds up. Yet, even here, in this least suitable of contexts, her painted head and shoulders cry out with desirability. And the pigment is the cry.

Such is the ancient mysterious contract between pigment and flesh. This contract permits the great Madonnas and Children to offer profound sensuous security and delight, just as it confers upon the great Pietàs the full weight of their mourning – the terrible weight of the hopeless desire that the flesh should live again. Paint belongs to the body.

123

Titian. Vanity of the World. 1515

The stuff of colours possesses a sexual charge. When Manet paints the

Déjeuner sur l’herbe

(a picture which Picasso copied many times during his last period) the flagrant paleness of the paint does not just imitate but becomes the flagrant nakedness of the women on the grass.

What the painting

shows

is the body

shown

.

The intimate relation (the interface) between painting and physical desire, which one has to extricate from the churches and the museums, the academies and the law-courts, has little to do with the special mimetic texture of oil paints, as I discuss in my book

Ways of Seeing

. The relation begins with the act of painting or watercolour. It is not the illusionist tangibility of the painted bodies which counts, but their visual signals, which have such an astounding complicity with those of real bodies.

Perhaps now we can understand a little better what Picasso did during the last twenty years of his life, what he was driven to do, and what – as one might expect – nobody had quite done before.

He was becoming an old man, he was as proud as ever, he loved women as much as he ever had, and he faced the absurdity of his own relative impotence. One of the oldest jokes in the world became his pain and his obsession – as well as a challenge to his great pride.

At the same time, he was living in an uncommon isolation from the world: an isolation, as I have noted, which he had not altogether chosen himself, but which was the consequence of his monstrous fame. The solitude of this isolation gave him no relief from his obsession; on the contrary, it pushed him further and further away from any alternative interest or concern. He was condemned to a single-mindedness without escape, to a kind of mania, which took the form of a monologue. A monologue addressed to the practice of painting, and to the dead painters of the past whom he admired or loved or was jealous of. The monologue was about sex. Its mood changed from work to work but not its subject.

The last paintings of

Rembrandt – particularly the self-portraits – are proverbial for their questioning of everything the artist had done or painted before. Everything is seen in another light. Titian, who lived to be almost as old as Picasso, painted towards the end of his life the

Flaying of Marsyas

and the

Pietà

in Venice: two extraordinary last paintings in which the paint as flesh turns cold. For both Rembrandt and Titian the

contrast between late and earlier works is very marked. Yet there also is a continuity, the basis of which is difficult to define briefly. A continuity of pictorial language, of cultural reference, of religion, and of the role of art in social life. This continuity qualified and reconciled – to some degree – the despair of the old painters; the desolation they felt became a sad wisdom or an entreaty.

With Picasso this did not happen, perhaps because, for many reasons, there was no such continuity. In art, he himself had done much to destroy it. Not because he was an iconoclast, nor because he was impatient with the past, but because he hated the inherited half-truths of the cultured classes. He broke in the name of truth. But what he broke did not have the time before his death to be reintegrated into tradition. His copying, during the last period, of old masters like Velázquez, Poussin, or Delacroix was an attempt to find company, to re-establish a broken continuity. And they allowed him to join them. But they could not join him.

And so, he was alone – like the old always are. But he was unmitigatedly alone because he was cut off from the contemporary world as a historical person, and from a continuing pictorial tradition as a painter. Nothing spoke back to him, nothing constrained him, and so his obsession became a frenzy: the opposite of wisdom.

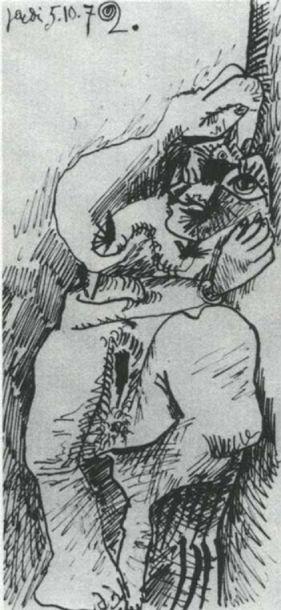

An old man’s frenzy about the beauty of what he can no longer do. A farce. A fury. And how does the frenzy express itself? (If he had not been able to draw or paint every day he would have gone mad or died – he needed the painter’s gesture to prove to himself he was still a living man.) The frenzy expresses itself by going directly back to the mysterious link between pigment and flesh and the signs they share.

It is the frenzy of paint as a boundless erogenous zone. Yet the shared signs, instead of indicating mutual desire, now display the sexual mechanism. Crudely. With anger. With blasphemy. This is painting swearing at its own power and at its own mother. Painting insulting what it had once celebrated as sacred. Nobody before imagined how painting could be obscene about its own origin, as distinct from illustrating obscenities. Picasso discovered how it could be.

How to judge these late works? It is too soon. Those who pretend that they are the summit of Picasso’s art are as absurd as the hagiographers around him have always been. Those who dismiss them as the repetitive rantings of an old man understand little about either love or the human plight.

Spaniards are proverbially proud of the way they can swear. They admire the ingenuity of their oaths, and they know that swearing can be an attribute, even a proof, of dignity.

Nobody ever swore in paint before.

124

Picasso. Nu couché. 1972

INDEX

Abstract art, freedom and

Apollinaire, Guillaume:

and Cubism,

1.1

,

1.2

death of,

1.1

,

1.2

and electricity

and the new poetry,

1.1

,

1.2

and

Parade

,

1.1

,

1.2

and Picasso’s genius

Aragon, Louis

Arcadia:

Bellini’s