The Sugar Barons (61 page)

As the British state, at huge expense, undertook to fight the international slave trade, an organised movement for the ‘Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery’ was inaugurated at the beginning of 1823. Once again, a vigorous campaign saw Parliament flooded with petitions. In the same year came a concerted attempt by East India traders, now importing sugar but not enjoying the favourable duties granted to Caribbean produce, to break the West Indians’ monopoly rights. From the start there was close cooperation between the two campaigns. The power of the West India lobby was still strong, but not enough to face both these attacks at the same time. A new boycott of West Indian products was launched, and the government ordered a general registration of all slaves on the islands and drew up rules for their treatment. Both moves were bitterly resisted by the islands’ assemblies, particularly in Jamaica.

The slaves themselves, a number of whom, thanks to the efforts of Nonconformist ministers on the islands – Moravians, Baptists and Methodists – could now read the newspapers, viewed these measures as a prelude to emancipation. When at first their hopes were dashed, a number decided to follow the example of the slaves of St Domingue. In 1816 there was a major rebellion in previously peaceful Barbados, followed by an even

more serious disorder in Jamaica in late 1831 that saw the deaths of 1,000 slaves and damage approaching a million pounds.

To blame, most white Jamaicans decided, were the growing number of Nonconformist ministers who had been educating and converting the islands’ slaves. Nine Baptist and six Methodist chapels were attacked and destroyed, and Baptist preacher William Knibb and four others were imprisoned. The ministers were later released, but the mob violence did nothing to endear the planters to the authorities at home, already angry at the resistance to their amelioration instructions and concerned that the next slave rebellion might actually suceed. Britain was now turning against its Caribbean colonists.

After intense public agitation against slavery, the election that followed the Great Reform Act in 1832 brought many more MPs into Parliament who were committed to the abolition of slavery. In May 1833, the Whig government introduced the Bill for the Abolition of Slavery. To ensure its passage, several large concessions were made: only those aged under six were to be freed straight away; other slaves would have to work out a period of unpaid ‘apprenticeship’ – effective slavery – for up to six years. Slaveowners would be compensated for their ‘loss’, the total sum allocated for this being around £20 million, a vast amount, equivalent to 40 per cent of the government’s annual budget. In August, the House of Lords passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which ended slavery in the British Empire, effective from August 1834.

The system of apprenticeship was never workable and collapsed four years later. Thus it was on 1 August 1838 when the 800,000 slaves of the British Empire, the vast majority of whom were in the West Indies, were truly freed.

The Baptist minister William Knibb held a service on the night of 31 July in his church in Falmouth, Jamaica. The walls were hung with branches, flowers, and portraits of Wilberforce and fellow abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. Into a coffin inscribed ‘Colonial Slavery, died July 31st, 1838, aged 276’, church members placed an iron punishment collar, a whip and chains. ‘The hour is at hand!’ Knibb called out from his pulpit, pointing to a clock on the wall. ‘The monster is dead!’ The congregation burst into cheers and embraced each other. ‘Never, never did I hear such a sound’, Knibb wrote. ‘The winds of freedom appeared to have been let loose. The very building shook at the strange yet sacred joy.’

Contrary to the hopes of Adam Smith, abolition failed to provide a willing and able free labour force in the British West Indies. Almost immediately

after abolition, the survival rate for black births and the life expectancy of African West Indians shot up, but many black former sugar workers turned their backs on the plantations and toil that would for ever carry the stigma of slavery. Canefields were left untended, and soon became overgrown with weeds. Attempts to replace the workforce with indentured Asians had indifferent success. Costs for the plantation owners rose, and profits dwindled.

But the decline and fall of the planters, and of the ‘first British empire’, was caused by more than abolition alone. Intermittent but often devastating war had taken a heavy toll on lives and property. Relentless disease and periodic intense natural disasters had made the islands a personal and financial risk no longer worth the returns. To blame, also, was the split with the North American colonies, curtailing a trading relationship of great benefit to both sides – but not London. The agricultural system in the British islands was moribund, and too often in the hands of disinterested managers. Competition from newly exploited tropical territories, such as Java and Madagascar, along with cheaper slave-grown product from Brazil, Dutch Surinam and Cuba, drove the sugar price ever downwards. At the same time, a growing sentiment towards free trade undermined the protectionism on which the wasteful system had long relied. To cap it all, the end of the 1820s saw a burgeoning of the beet sugar industry in Europe. As decay became every day more apparent, so disillusionment and malaise set in among the British planters.

The continued resistance of the enslaved population had also contributed to the collapse of the world of the plantation, but in truth, as a society it had failed long before. Slavery, ‘an inferior social and economic organisation of exploiters and exploited’, had sacrificed human life and its most precious values to the pursuit of immediate gain. The sugar-and-slave business had encouraged greed, hypocrisy, fear and brutality, corrupting almost everyone it touched.

The sugar money, flashed around in England, had never smelt quite right. Now, for many in Britain, the whole West Indian imperial adventure stank, and was cause for national regret. The poet Robert Southey, brother of a naval officer stationed in tropical American waters early in the nineteenth century, expressed a view widely held in England, describing the colonies as ‘perhaps as disgraceful a portion of history as the whole course of time can afford; for I know not that there is anything generous, anything ennobling, anything honorable or consolatory to human nature to relieve it, except what may relate to the missionaries’.

Instead, Britain’s imperial focus, the ambitions of her brightest and best, had for a while been turning east. The West India planter, flaunting his

wealth, was yesterday’s man. The new grandees were the East India nabobs, and on the horizon was a more nuanced form of imperialism, which attempted to combine the sugar empire’s greed and exploitation with an urge to ‘civilise’ – to convert, educate and thus subject in a subtler way than the overt racial slavery, the shameful and shaming imperialism, ‘red in tooth and claw’, of the Sugar Barons.

I am grateful to the K. Blundell Trust, administered by the Society of Authors, for a grant towards the costs of researching this book.

My greatest debt is to the scholars who have produced a rich academic literature on West Indian history, including transcriptions of key documents. Their help with identifying and interpreting the primary sources has been very valuable.

Writing about West Indian history has, unsurprisingly, been dominated by a concern with slavery and, influenced in part by the nature of a lot of the source material, with the economics of the plantation system. For this reason, I have tried to focus on other aspects of the time, although, of course, neither can be ignored, and specialists on these topics have also helped shape this book. In particular, I would like to acknowledge my great debt to (and recommend as further reading): Susan Amussen, Bernard Bailyn, Hilary Beckles, the Bridenbaughs, Vincent Brown, Trevor Burnard (especially), Linda Colley, Michael Craton, Noel Deerr, Richard Dunn, David Eltis, David Galenson, Larry Gragg, Douglas Hall, Vincent Harlow, Russell Menard, Sidney Mintz, Vere Oliver, Andrew O’Shaughnessy, Gabriel Paquette, Richard Pares, Lowell Ragatz, Richard Sheridan, Simon Smith, Peter Thompson, Karl Watson and Eric Williams.

I am grateful to all the academics who shared their research and gave this project encouragement, as well as others who sent me letters or pictures, or provided leads and contacts: Tim Anderson; David Beasley, Librarian, The Goldsmiths Company; Chris Codrington of Florida; Professor Madge Dresser; Michael Hamilton; Charles Freedland; Maya

Jasanoff, Steve Jervis; Louisa Parker; Victoria Perry; Derek Seaton; Paul Vlitos; Brian Wessely.

I am much indebted to the staff of a number of local and national archives in the UK including: the British Library, especially the staff of the Rare Books and Manuscripts reading rooms; the Bodleian Library in Oxford, in particular Lucy McCann; the Public Records Office and the county archives of Sussex and Lincolnshire. I am indebted for help with picture research to the brilliant staff of the National Portrait Gallery in London. In the United States, I was given valuable assistance by Kim Nusco in the John Carter Brown Library, Bert Lippincott at the Newport Historical Society, and by the staffs of the Rhode Island Historical Society and the Redwood Library. From Jamaica I would like to thank John Aarons, Audene Brooks at the Jamaica National Heritage Trust, George Faria, Tony Hart, Geoffrey and Patricia Pinto, as well as all at the National Library, the National Archives in Spanish Town and the Jamaica Institute. Special thanks to the late, much-missed Ed Kritzler, who showed me another world in Roaring River, Westmoreland. In Barbados, I was lucky enough to enjoy the enthusiastic support and local historical expertise of Mary Gleadall, and the assistance of Joan Braithwaite at the Barbados Museum archives, and of the staff of the National Archives at Black Rock.

A thousand thanks to Professor Barbara Bush for her careful checking of the manuscript and for her enthusiasm and advice. All errors, remain, of course, my own.

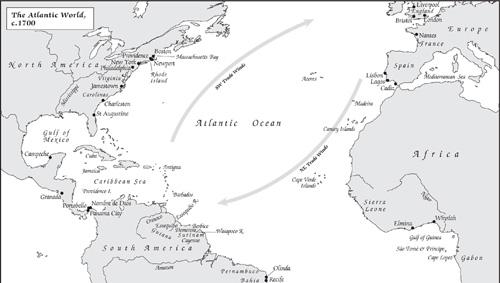

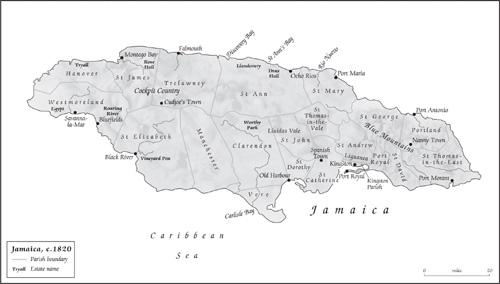

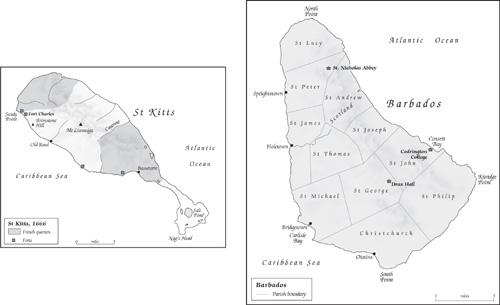

I was immensely lucky that the excellent Martin Brown was able to spend the time to draw the maps for the book, and in my copy-editor Jane Selley, proof-reader Mask Handsley and indexer Andy Armitage.

Indeed, books like this are a team effort. I have been fortunate to have two editors of huge experience and expertise in Tony Whittome at Hutchinson and George Gibson at Walker Books in the US, both of whom took the time to roll up their sleeves and get involved in the nitty-gritty of the manuscript, as well as providing encouragement and advice. I am grateful to Caroline Gascoigne and all at Random House and Walker Books who have helped with publishing this book, and for their patience when the research took much longer than planned. Thanks also to my agents Julian Alexander in London and George Lucas in New York, and to all my friends and family who have read and commented on drafts, in particular my father David Parker, and my father-in-law Paul Swain.

Lastly, much love and thanks to Hannah, Milly, Tom and Ollie, my most special ones.

Other books

Stargate by Pauline Gedge

The Rancher's Bride by Dina Chapel

Nether Regions by Nat Burns

Diamond Eyes by A.A. Bell

Christmas on the Last Frontier (Last Frontier Lodge #1) by J.H. Croix

The Wandering (The Lux Guardians, #2) by Saruuh Kelsey

Blink of an Eye: Beginnings Series Book 8 by Jacqueline Druga

Gideon's Sword by Douglas Preston

Sebastian Darke: Prince of Explorers by Philip Caveney

Forever Sheltered by Deanna Roy