The Sugar King of Havana (20 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

It is a telling revelation. Although Lobo’s obvious worry about the future of

la casa

is a mark of his concern for others and the continuity of their lives above his own, his despair at being proved wrong by more powerful and implacable historical forces is a sign of how strongly he believed in his own abilities. Lobo, after all, was a man “used to getting what he wanted,” as Ely said. That was true even if it meant facing death, as Lobo soon would again, when his stubborn unwillingness to accommodate himself to others provoked a hail of bullets in a Havana drive-by shooting. Such violence was the Janus face of Cuba’s and of Lobo’s coming golden age.

la casa

is a mark of his concern for others and the continuity of their lives above his own, his despair at being proved wrong by more powerful and implacable historical forces is a sign of how strongly he believed in his own abilities. Lobo, after all, was a man “used to getting what he wanted,” as Ely said. That was true even if it meant facing death, as Lobo soon would again, when his stubborn unwillingness to accommodate himself to others provoked a hail of bullets in a Havana drive-by shooting. Such violence was the Janus face of Cuba’s and of Lobo’s coming golden age.

Seven

THE EMERALD WAY

Among the skirts of Turquino

The road of emeralds, oh!

Invites us to take our ease;

The love struck campesino

Among the skirts of Turquino

Sings and loves as he may please.

The road of emeralds, oh!

Invites us to take our ease;

The love struck campesino

Among the skirts of Turquino

Sings and loves as he may please.

—JOSÉ MARTÍ

A

fter Lobo’s brush with disaster betting against the Germans, most of Cuba had a quiet Second World War, although the country joined the Allied war spirit with enthusiasm. My grandmother composed a song, “Fire over England,” and mailed it to Winston Churchill. His office replied: “Enjoyed the music, especially the spirit in which it was written.” Several hundred Cubans enlisted in the U.S. Army, and the government executed a German spy: Heinz Lüning, known as the “Canary” because he kept birds in his apartment to mask the sound of his radio transmissions, was the only spy to be shot in Latin America during the war. German submarines could be seen from the Havana waterfront prowling the sea, and as part of the war effort a blackout was ordered in all coastal towns. Havana’s lights stayed off only for a week, the German subs continued to sink ships, and sometimes the Malecón was plunged ankle deep in oil from the tankers torpedoed off the northern coast. Shortages and rationing increased. The tourist trade collapsed, and Britain—Cuba’s largest market for tobacco—banned Cuban cigar imports as an unnecessary luxury. Even so, conflict in Europe found Cuba where it always was when the rest of the world was gripped by war: ready to make a profit.

fter Lobo’s brush with disaster betting against the Germans, most of Cuba had a quiet Second World War, although the country joined the Allied war spirit with enthusiasm. My grandmother composed a song, “Fire over England,” and mailed it to Winston Churchill. His office replied: “Enjoyed the music, especially the spirit in which it was written.” Several hundred Cubans enlisted in the U.S. Army, and the government executed a German spy: Heinz Lüning, known as the “Canary” because he kept birds in his apartment to mask the sound of his radio transmissions, was the only spy to be shot in Latin America during the war. German submarines could be seen from the Havana waterfront prowling the sea, and as part of the war effort a blackout was ordered in all coastal towns. Havana’s lights stayed off only for a week, the German subs continued to sink ships, and sometimes the Malecón was plunged ankle deep in oil from the tankers torpedoed off the northern coast. Shortages and rationing increased. The tourist trade collapsed, and Britain—Cuba’s largest market for tobacco—banned Cuban cigar imports as an unnecessary luxury. Even so, conflict in Europe found Cuba where it always was when the rest of the world was gripped by war: ready to make a profit.

Sugar prices rose, as did production. The 1944 crop hit 4.3 million tons, the largest since 1930, and fetched $330 million, the highest since 1924. Cuban good times promised to reach the same dizzying heights they had in the 1920s. Furthermore, the country was on the brink of a twelve-year period of democratic rule. Batista resigned from the army in 1939 to run for president—he never wore a military uniform again,

el mulato lindo,

the pretty mulatto, as he was known, preferring immaculate white linen suits instead. The next year he won the elections, supported by the Communist Party. Batista, so far removed from the dictator he later became, then called for a constituent assembly. The result was a new constitution, seen throughout the Americas as a model of progressive legislation where workers, for example, were guaranteed paid vacations. Grau, the old revolutionary leader, won the next election in 1944 and Batista, contrary to expectations, left quietly for Daytona Beach, Florida, where he lived in baronial style to sit out “a pleasant exile in some of the New World’s toniest suites,” as

Time

magazine put it.

el mulato lindo,

the pretty mulatto, as he was known, preferring immaculate white linen suits instead. The next year he won the elections, supported by the Communist Party. Batista, so far removed from the dictator he later became, then called for a constituent assembly. The result was a new constitution, seen throughout the Americas as a model of progressive legislation where workers, for example, were guaranteed paid vacations. Grau, the old revolutionary leader, won the next election in 1944 and Batista, contrary to expectations, left quietly for Daytona Beach, Florida, where he lived in baronial style to sit out “a pleasant exile in some of the New World’s toniest suites,” as

Time

magazine put it.

Cuba lived through much of the war years in a halcyon haze. Grau promised everyone “a pot of gold and a rocking chair.” My grandfather’s store flourished on San Rafael Street, near Galliano, a street corner known in Havana for its

piropos

—the unsolicited compliments, comments, and tributes that Cuban men made to female beauty, not always welcomed but often. More innocently, my mother went to school at the Convent of the Sacred Heart, where the nuns forbade their charges from watching

Gone with the Wind

because of the morning-after scene in which a ravished Scarlett O’Hara wriggled in bed with sensuous delight, having been carried off the night before in the arms of her husband, Rhett Butler.

piropos

—the unsolicited compliments, comments, and tributes that Cuban men made to female beauty, not always welcomed but often. More innocently, my mother went to school at the Convent of the Sacred Heart, where the nuns forbade their charges from watching

Gone with the Wind

because of the morning-after scene in which a ravished Scarlett O’Hara wriggled in bed with sensuous delight, having been carried off the night before in the arms of her husband, Rhett Butler.

Lobo and María Esperanza moved into a new house in Miramar, a comfortable and modern mansion with a large garden built in a revival colonial style. Their daughters were away during the school year at Rydall, a small boarding school in Pennsylvania, and thence Ethel Walker in Connecticut, where they had been sent to get a proper education, as Lobo put it. Lobo and María Esperanza went to the best parties, his wealth and her position ensured entrée everywhere, and the couple lacked for nothing—although Lobo preferred to live simply. “I have no yacht,” he said. “Frugality is a virtue rather than a vice.”

Meanwhile, at

la casa

, Lobo changed with the times. To date he had only worked as a financial speculator, buying and trading sugar. Now he started to purchase mills. It was a huge strategic shift, given his disastrous first attempt as a sugar producer at Agabama, when the cane rollers had collapsed in the middle of the grinding season and he had lost most of the harvest. In 1943 he bought Pilón, a midsize mill in the far east of the island in Oriente Province. The next year he bought Tinguaro

.

A one-hour drive from the beach at Varadero, and three hours from Havana, Tinguaro lies in the red-earth sugar plains of Matanzas and soon became Lobo’s favorite mill, his country house. Other plantations followed quickly: San Cristóbal in 1944, Fidencia and Unión in 1945, Caracas in 1946, Niquero in 1948, Pilar and Tánamo in 1951. None of them was large but together they made a massive operation. By the end of the 1950s, Lobo’s mills together produced over half a million tons of sugar, almost 9 percent of the Cuban harvest. The crop they milled each year was worth some $50 million.

la casa

, Lobo changed with the times. To date he had only worked as a financial speculator, buying and trading sugar. Now he started to purchase mills. It was a huge strategic shift, given his disastrous first attempt as a sugar producer at Agabama, when the cane rollers had collapsed in the middle of the grinding season and he had lost most of the harvest. In 1943 he bought Pilón, a midsize mill in the far east of the island in Oriente Province. The next year he bought Tinguaro

.

A one-hour drive from the beach at Varadero, and three hours from Havana, Tinguaro lies in the red-earth sugar plains of Matanzas and soon became Lobo’s favorite mill, his country house. Other plantations followed quickly: San Cristóbal in 1944, Fidencia and Unión in 1945, Caracas in 1946, Niquero in 1948, Pilar and Tánamo in 1951. None of them was large but together they made a massive operation. By the end of the 1950s, Lobo’s mills together produced over half a million tons of sugar, almost 9 percent of the Cuban harvest. The crop they milled each year was worth some $50 million.

Becoming an

hacendado,

or mill owner, brought the social cachet and sense of aristocracy still attached to land ownership from the colonial years. Roland Ely, steeped in the history of that era, attached great importance to this. “Lobo only ever bought mills because he wanted to belong to the old school club,” he told me—although it is hard to believe this was the case. Lobo had married into the oldest of Cuban families, the Montalvos, while his brother had married a Menocal, a relative of the third president of the Republic. His sister meanwhile had married Mario Montoro, son of the old Autonomist and a respected politician after independence. Lobo’s lawyer León suggested a simpler reason. Lobo bought mills “because there was money to be made.”

hacendado,

or mill owner, brought the social cachet and sense of aristocracy still attached to land ownership from the colonial years. Roland Ely, steeped in the history of that era, attached great importance to this. “Lobo only ever bought mills because he wanted to belong to the old school club,” he told me—although it is hard to believe this was the case. Lobo had married into the oldest of Cuban families, the Montalvos, while his brother had married a Menocal, a relative of the third president of the Republic. His sister meanwhile had married Mario Montoro, son of the old Autonomist and a respected politician after independence. Lobo’s lawyer León suggested a simpler reason. Lobo bought mills “because there was money to be made.”

Many Cuban plantations were still owned by foreign banks after the 1930s bust, and were often run poorly and unprofitably from New York. “You could pick up mills cheaply in those days,” León remembered. Lobo also needed to channel his energies into new arenas. Because of the war, Cuba presold its whole 1944 crop to the United States, and fixed prices elsewhere limited the scope for Lobo’s speculations. International diversification provided one release. Buying sugar mills was another. Lobo would now not only sell other planters’ sugar, warehouse it, and arrange for their cargos to be shipped abroad, he would produce it too.

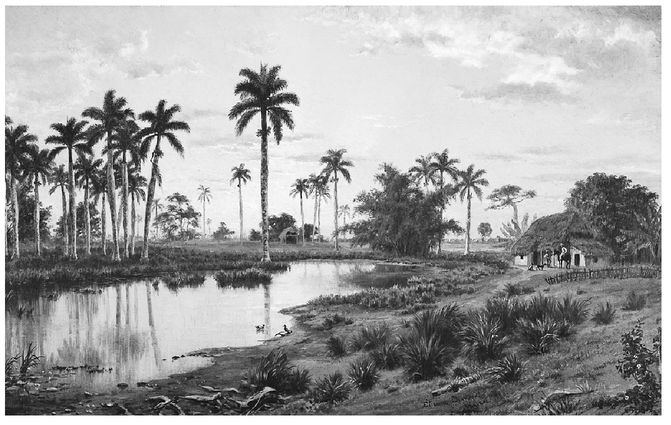

Rural Cuba was also largely at peace with itself. Living conditions outside the major cities were often miserable and still the subject of periodic exposés by the Cuban press. Yet the violent strikes and labor problems of 1933 had passed, thanks to the growing prosperity and also to legislation enacted after the Depression. “Everything was legally organized, there was a structure to follow,” León remembered. “There were unions, the Ministry of Labor was involved. Worker relations were generally cordial, even friendly. Disputes were treated as a constant process of negotiation. . . . It was almost a formal process.” So formulaic did this process become that the government also fixed the date the harvest began and controlled the amount of international sales, domestic production quotas, the local price of cane, the amount of worker holidays, and their salaries too. Although Castro’s government usually depicts prerevolutionary Cuba as a place of savage and exploitative capitalism, the last time the industry was genuinely liberal was in the 1920s, and by the 1940s large parts of the economy were state-run. It was a stable system, but also a stagnant one.

The sugar industry settled into the ordered routine of a sugarcrat’s prosperous middle age. The annual cycle—first the

zafra

, then the

tiempo muerto

or dead season—was as regular as breathing. First came the inhalation every December, when mill owners once again borrowed funds to pay the workers to cut and mill the cane. In the countryside, families began to purchase meat, rice, new clothes, and shoes. Traveling salesmen ventured out of Havana and crowded the second-class hotels in rural towns. The railroads took on extra helpers, as did the ports. Lights began to appear about the countryside as rural Cubans once again had enough money to buy kerosene. Everything quickly assumed an air of prosperity as credit flowed around the island once more. Then came the exhalation a few months later when the harvest ended and the kerosene lamps inside the countryside’s thatched

bohios

flickered out.

zafra

, then the

tiempo muerto

or dead season—was as regular as breathing. First came the inhalation every December, when mill owners once again borrowed funds to pay the workers to cut and mill the cane. In the countryside, families began to purchase meat, rice, new clothes, and shoes. Traveling salesmen ventured out of Havana and crowded the second-class hotels in rural towns. The railroads took on extra helpers, as did the ports. Lights began to appear about the countryside as rural Cubans once again had enough money to buy kerosene. Everything quickly assumed an air of prosperity as credit flowed around the island once more. Then came the exhalation a few months later when the harvest ended and the kerosene lamps inside the countryside’s thatched

bohios

flickered out.

Lobo accommodated himself to this regularity and his work continued much as before. As an

hacendado,

he now described himself as 90 percent sugar producer—and also 90 percent financial operator. Routine management of his mills was delegated to adept administrators, poached from competitors when need be. (“How much does Rionda pay you?” he asked Tomás Martínez, chief engineer at the Manatí, Cuba’s fourth-largest mill. “$25,000? I’ll pay you $35,000.” Martínez joined Lobo’s team.) Beginning on Monday morning, Lobo still financed and traded sugar through the week at Galbán Lobo. It was only after markets closed on Friday afternoon that his life changed gear. He climbed aboard an ingenious cot strapped into the back of a car, slept overnight while he was driven through the Cuban countryside, and woke up at one of his mills the next day.

hacendado,

he now described himself as 90 percent sugar producer—and also 90 percent financial operator. Routine management of his mills was delegated to adept administrators, poached from competitors when need be. (“How much does Rionda pay you?” he asked Tomás Martínez, chief engineer at the Manatí, Cuba’s fourth-largest mill. “$25,000? I’ll pay you $35,000.” Martínez joined Lobo’s team.) Beginning on Monday morning, Lobo still financed and traded sugar through the week at Galbán Lobo. It was only after markets closed on Friday afternoon that his life changed gear. He climbed aboard an ingenious cot strapped into the back of a car, slept overnight while he was driven through the Cuban countryside, and woke up at one of his mills the next day.

The frequency of these unannounced visits set Lobo apart from the tradition of absentee planters, so coruscated by the Condesa de Merlin, who spent their days idly in Havana; or the mill owner that the former slave Esteban Montejo remembered riding past in a carriage “with his wife and smart friends through the cane fields, waving a handkerchief, but that was as near as he ever got to us.” Lobo did not travel to his mills as a tourist. “One of the things I learnt is that you cannot manage a mill by remote control,” he said. Lobo tromped through the

batey

, issued instructions, and stopped to talk with workers whom he called by name and who knew him as Julio in turn.

batey

, issued instructions, and stopped to talk with workers whom he called by name and who knew him as Julio in turn.

This lack of pretension was one of Lobo’s most appealing features, and he fostered the same spirit among his daughters. Not for them the closeted existence of their mother, a throwback to the sheltered lives of the colonial years, when women of good breeding passed their time applying a powdered eggshell cosmetic called

cascarilla

. When Leonor and María Luisa went to the yacht club, Lobo insisted, they would “travel on the bus,” Route 32.

cascarilla

. When Leonor and María Luisa went to the yacht club, Lobo insisted, they would “travel on the bus,” Route 32.

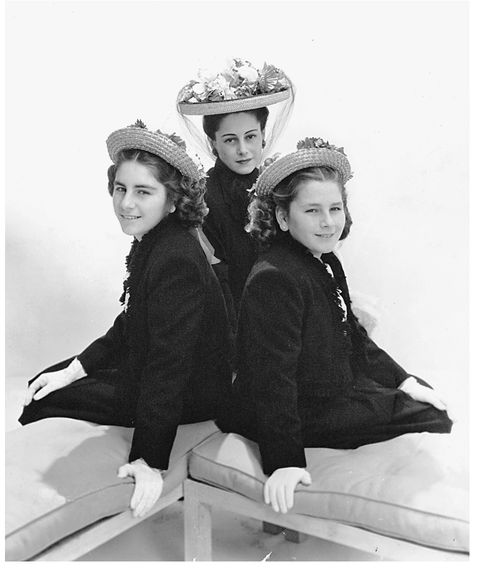

Leonor, María Esperanza, and María Luisa, c. 1945.

Such instructions show that Lobo was an engaged parent, even down to mundane details such as the state of his daughters’ teeth, sometimes sending peremptory handwritten notes to their dentist. However, Lobo also brought home the divide-and-rule strategy he followed at work. His two young daughters did not then know of his love affairs and mistresses, so he played the innocent victim to María Esperanza’s temper. Perhaps as a consequence, a deep rivalry developed between Leonor and María Luisa for their father’s affections. María Luisa remembered that as children, whichever sister behaved best would have the honor, “the great honor,” of lighting their father’s cigar, “and putting on, as a ring, the golden paper cigar band.”

Other books

Indigo [Try Pink Act Two] by Max Ellendale

The Sweet Gum Tree by Katherine Allred

The Sheep Look Up by John Brunner

Now You See It by Richard Matheson

The House on Flamingo Cay by Anne Weale

Wild and True: A Frankie Love Escape by Frankie Love

Cellular by Ellen Schwartz

Always Watching by Brandilyn Collins

Facing the Hunchback of Notre Dame by Zondervan

The Union by Tremayne Johnson