The Sugar King of Havana (18 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

When Lobo wrote to Gerry Asher, one of his principal traders in New York, that he was always “seeking, prying and executing on information. Our business, as you know, [is] based on good, exact and fast information—the secret [is] how to interpret that news rapidly,” he was merely echoing the practices of Cuban speculators down the years and other speculators everywhere. In the nineteenth century, the planter and trader Tomás Terry used to note down in a little black book the daily exports and imports of Cienfuegos so he could divine the trading positions of his competitors.

Speculators also have a natural enthusiasm for any technology that brings markets closer to the centers of the financial world, be that the telephone or the radio, railways or air flight. That is why Cuba has always been a communications center. Pan American Airways began its life early in the twentieth century on the Havana–Key West route, and the first submarine telephone cable linking the United States to another country was laid across the Florida Straits to Havana in April 1921. When President Harding finished a brief call to his Cuban counterpart President Menocal that marked the occasion, Sosthenes Behn, the president of the Cuban Telephone Company, declared that the cable was only a first step in creating a communications hub in Havana that would span South and North America. A few years later, Behn’s holding company, International Telephone & Telegraph, bought AT&T’s international operations and built up large businesses throughout Europe and the Americas.

Cubans also have a particular fondness for speculative wagers. Before Castro, Cubans bet on cockfights, the lottery, jai alai, horse races, baseball, and every sort of device the casinos could think of. It is only a short step from gambling to high finance. “It is worth recording,” wrote the American historian Leland Jenks of the Dance of the Millions, “that there developed in Cuba between 1917 and 1920, under indigenous control, most of the phenomena of speculation, industrial combination, price fixing, bank manipulation, pyramiding of credits and over-capitalization which we are accustomed to regard as the peculiar gift of the high civilized Anglo-Saxons.” This was despite the fact that the Havana stock market never amounted to much, with only eighty members and sixty listed companies, and no more than a handful of stocks ever traded. Even so, as Jenks wrote, Cubans have “an astonishing aptitude for the most advanced refinements of high finance.”

It may be that this “astonishing aptitude” stems from a Cuban abundance of the irreverent and anarchic spirit which is so central to speculation. Like the commercial fairs in medieval Europe, which it grew out of, the speculative spirit delights in subverting the established order. That is why great speculative moments are sometimes described as “carnivals of speculation.”

The gulf between Cuba’s vibrant merchant past and its commercially sterile present is huge, as is the paradox. Although a nation of naturally savvy entrepreneurs, Cuba has been subject to a half-century experiment in socialism that has ground most of the economy into the dust.Of course, the U.S. embargo has exacted a toll. When I spoke with Leal of this, he had compared the island to a huge sugar mill with the embargo a bung jammed into the chimney. “The blockade has to be released, otherwise the mill will be filled with smoke and fire,” he said. Yet there is also the heavier economic cost exacted by what ordinary Cubans call the “internal embargo.” This is the thicket of bureaucracy and the government’s traditional antipathy to individual enterprise that can turn even shopping for groceries into a surreal excursion. “Pssst,” someone had whispered to me from a dark Havana doorway in the early 1990s, as if he were a pimp or a drug dealer. “Want to buy some cabbage?”

Restrictions have subsequently been relaxed somewhat, and Cubans have quickly demonstrated their entrepreneurial capacities whenever the government has let them; in private farming, say, or operating small restaurants. In 2008, Cubans were allowed to stay at hotels previously reserved for tourists—so long as they had the dollars to pay the bill—and buy cell phones (although not toasters). Restrictions may well be lifted further. Even so, the possibility that a private citizen might be allowed again to own a mobile phone or toaster

company

remains, for now, a long way off.

company

remains, for now, a long way off.

THE FRONT DOORS of the old Galbán Lobo office on Obispo were barred and sealed, and entry was around the back through a parking lot on O’Reilly. A guard sitting at a plastic desk inside the back door said he was sorry that the building was so dirty. With that faint apology, he waved me through.

Inside, there was the usual disrepair. The windows were cracked, and office doors with handwritten signs like

Supervisor

and

Economics Department

had been jammed shut, nails hammered into the locks. A paper sign stapled onto one wall had the single word

School

written in faint pencil above a rough arrow pointing down a long corridor. The last time Lobo had seen the office after his fateful interview with Che Guevara, the rooms had been taped up and loose papers covered the floor. Now it was in a similar state, as the state firms that occupied the building packed their boxes and moved on.

Supervisor

and

Economics Department

had been jammed shut, nails hammered into the locks. A paper sign stapled onto one wall had the single word

School

written in faint pencil above a rough arrow pointing down a long corridor. The last time Lobo had seen the office after his fateful interview with Che Guevara, the rooms had been taped up and loose papers covered the floor. Now it was in a similar state, as the state firms that occupied the building packed their boxes and moved on.

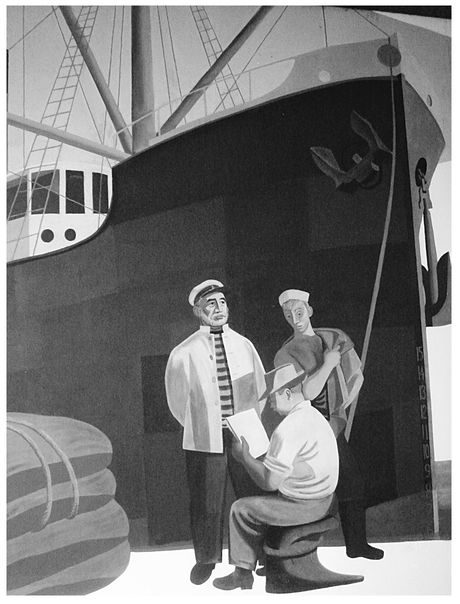

Galbán Lobo mural, Old Havana.

“The place is a labyrinth,” apologized one office worker with short hair and green eyes who offered to show me around. “All the offices have been boxed up by these partitions to make more space,” he explained, thumping a drywall in a cramped room. Even so, I could still make out the basic layout of the old office; three floors of rooms arranged like figures of eight around two inner courtyards. One of these, a colonial patio overgrown with plants, had an old well in the center and a statuette of San Ignacio set in a mossy niche above a studded wooden door; this was the former main entrance. Downstairs around the second, larger courtyard was the sugar mural that Lobo had commissioned to illustrate the harvest, and which office managers, clerks, and secretaries would have walked past every day. It began on one side with a barefoot worker wearing a straw hat, stooped over in a plowed field, planting seeds. Subsequent panels showed cane cutters, the cane then loaded into a wagon, oxen pulling the wagon to a mill, and a mechanic with a greasing can who stood next to a huge boiler. The sugar then spilled out of vast chutes into jute bags held by bare-chested men with thickly muscled arms and calm, classically Greek faces. The final scene showed an official holding a clipboard and sitting on a bollard at a quay, a ship behind him. It could have been Lobo.

Lobo’s own office was on the first floor. Downstairs would have been a central switchboard, where women wearing headphones took calls and plugged phone wires into flashing equipment. Around it there would have been rooms filled with neat rows of clerks’ desks, each topped by a sturdy black typewriter and a bakelite phone, and a sugar laboratory that looked like an old-fashioned doctor’s surgery with labeled glass bottles on shelves above a wooden workbench. Phones rang, telexes chattered, and typewriters clacked amid the daily hubbub. “A fat blond man is summoned into one office by an urgent voice,” wrote a Cuban journalist in 1937 in a profile of a day at Galbán Lobo. “An American comes out of the other with the step of a victor. Two other ruddy Americans go in. Someone gives a final order. Another one protests.” The voices came from the trading room. “There is commotion. The whole place seems like a cyclone,” the journalist concluded, drawing a scene of colorful confusion instantly recognizable to anyone who has seen the floor of the New York Stock Exchange or the trading pits of the Chicago commodity market.

It takes a man of rare qualities to rise above such a fray. But at his trading desk, Lobo floated above the market noise even as he sat in the thick of it, feeling its vibrations and flows, his mind the gnomic center of a trading operation that leaned with and sometimes directed the market traffic. Lobo was constantly immersed in information. To the right of his desk sat a personal telephone operator. Over her head, stretching along the wall, ran a blackboard on which international sugar prices were chalked, erased, and revised. In front of Lobo stretched two rows of facing desks, each occupied by an assistant who could supply detailed information about a specific aspect of the business. At Lobo’s left hand was a ticker that spat out news from the New York exchange, and beyond that another telex that kept Lobo in touch with his New York representative, Olavarría & Co., and his other agents around the world. The markets whirled around him. By his own admission, he stood ready to buy or sell, at almost any hour of the day, any quantity of sugar that was offered or solicited by anyone, anywhere. Even so, Lobo contained his extreme mental activity within a physical stillness that many commented on. “The difficulty,” Lobo confided to one competitor, Maurice Varsano, a French sugar merchant, “is that our business is one where all the excitement and nerves should take place inside, and not with frantic movement.”

Although the speculative business is filled with confusing jargon—from longs and shorts to bulls and bears, straddles, butterflies, and strikes—Lobo’s essential skill, like that of any trader, was simple: to make accurate judgments about what the market was going to do next. This is more than just thinking about whether markets will go up or down; it is about handling uncertainty. In financial circles, this is known as “risk.” As Keynes argued, the speculator “is not so much a prophet (though it may be a belief in his own gifts of prophecy that tempts him into the business) as a

risk-bearer

. If he happens to be a prophet also, he will become extremely, indeed preposterously, rich.” Lobo was certainly a risk-taker, yet always denied that any special ability—such as miraculous foresight—lay behind his success. Arturo Mañas, the powerful head of Cuba’s Sugar Institute in the 1950s, put it succinctly. Lobo’s achievements, he once wrote, are “not due to clairvoyance or some ability to see into the future but rather that he worked harder than the rest.”

risk-bearer

. If he happens to be a prophet also, he will become extremely, indeed preposterously, rich.” Lobo was certainly a risk-taker, yet always denied that any special ability—such as miraculous foresight—lay behind his success. Arturo Mañas, the powerful head of Cuba’s Sugar Institute in the 1950s, put it succinctly. Lobo’s achievements, he once wrote, are “not due to clairvoyance or some ability to see into the future but rather that he worked harder than the rest.”

Lobo had a legendary appetite for work. Brokering in those days was often a leisurely activity begun at ten o’clock, with a long break for lunch. By contrast, Lobo’s days began at dawn. An office boy arrived at his house at 6:30 each morning, carrying a clutch of decoded cables that had been sent overnight from Lobo’s agents in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Lobo worked his way through the messages over breakfast, wrote his replies, and the office boy would return to Galbán Lobo to code the telexes and send them off. Lobo then drove his daughters to school, dressed in his usual white linen trousers and starched white guayabera, and continued to his office in Old Havana. When he arrived at about eight o’clock, replies from his morning cables waited for him. “In that way, I gained a huge advantage over my competitors, who got into their Wall Street offices at 10am,” Lobo said.

At his peak, Lobo handled almost half of Cuba’s sales to the United States, half of Puerto Rico’s, and some 60 percent of the Philippines’ sugar. Some believed the sheer size of this operation gave him a dangerous ability to rig market prices to his own benefit and to the industry’s harm. It was all part of the mythic market power that Leal had commented on. Lobo’s response to such talk was always to shrug. “No man can control a commodity as big as this. That’s absurd.”

Still, Lobo’s massive position in the sugar market did make him a dominant and often forbidding figure. “He was used to getting what he wanted,” the U.S. historian Roland Ely told me. Now in his nineties, Ely has a hangdog face and lidded eyes and is one of the few people still alive who knew Lobo’s work life before the revolution. They first met in New York in 1951 when Ely was cataloguing the business correspondence of Moses Taylor, a nineteenth-century merchant who amassed one of the United States’ largest fortunes, largely from trading sugar with Tomás Terry, the “Cuban Croesus.” Intrigued by Ely’s work, Lobo invited him to stay in Havana, making available his library of Cuban history books—Ely said it was one of the most extensive he had seen—and opening doors for the historian on the island, including to the moldering Terry archive in Cienfuegos. Ely’s subsequent book

Cuando Reinaba Su Majestad El Azúcar

, “When Sugar Reigned in All Its Glory,” is considered a fundamental piece of Cuban scholarship. “Lobo had an outsized ego, you know,” Ely commented to me.

Cuando Reinaba Su Majestad El Azúcar

, “When Sugar Reigned in All Its Glory,” is considered a fundamental piece of Cuban scholarship. “Lobo had an outsized ego, you know,” Ely commented to me.

This ego often made Lobo unpopular with his peers, as did his almost Napoleonic refusal to flinch from the prospect of conflict. “The sugar b[usines]s has mostly been handled by gentlemen and we don’t propose to keep such racketeers in the b[usines]s as Lobo,” George Braga from Rionda’s Cuban Trading had vainly blustered in early 1940, when drinking had dulled Braga’s edge amid the Sugar Exchange’s cutthroat operations. Yet that “gentlemanliness” was often just a byword for a cozy Cuban world of mutual back-scratching that Lobo often upset. In 1944, Lobo publicly denounced an illegal sugar sale that another speculator, Francisco Blanco, had hoped to broker with Ecuador, forcing its cancellation and so beginning the two men’s lifelong rivalry.

Other books

Melanie Travis 06 - Hush Puppy by Berenson, Laurien

Killer by Francine Pascal

Real Life by Sharon Butala

Seven Lies by James Lasdun

En la arena estelar by Isaac Asimov

The Law of Angels by Cassandra Clark

Demonkin by T. Eric Bakutis

Baby Island by Brink, Carol Ryrie, Sewell, Helen

Nakoa's Woman by Gayle Rogers

A Life Unplanned by Rose von Barnsley