The Sugar King of Havana (3 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

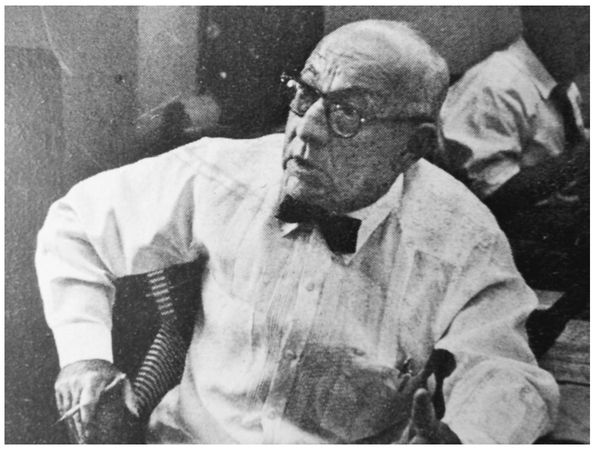

Lobo in his trading room.

Short and stern-faced, balding but with a strong jaw, Lobo was then the most important force in the world sugar market. Sixty-two years old, he was known as an authoritarian empire builder who handled about half the six million tons of sugar that Cuba produced annually. As part of his personal fortune, he controlled fourteen sugar mills in Cuba, owned hundreds of thousands of acres of land, and had trading offices in New York, London, Madrid, and Manila. He also owned a bank, Banco Financiero, an insurance company, shipping interests, and the telecommunications firm Inalámbrica. Some of Lobo’s wealth derived from his father, who had fled to Havana from Venezuela in 1900 and entered into a profitable partnership with a Spanish private banker and importer. But Lobo had built most of his empire subsequently, by himself. A speculator and financier of genius, one business competitor observed with grudging awe that Lobo “doesn’t sense a trend, he smells it.”

There was more to Lobo than money and sugar, though. He was a cultured man, famed for his private collection of art and the largest holding of Napoleonica outside France, including one of the emperor’s back teeth and his death mask—the revealing interest of a man who sought to project his ambition and sense of self by association with Napoleon. Politically, he was an enigma. Lobo’s wealth made him an emblem of prerevolutionary Cuban capitalism, of everything that Fidel Castro would eventually purge from the island. By marriage, he was linked to the remarkable Condesa de Merlin, who had married one of Napoleon’s generals and whose uncle, Lorenzo Montalvo, the Julio Lobo of his day, introduced the first steam-powered sugar mill to the island. With a due sense of dynasty, Lobo had even christened his eldest grandchild with cane juice in the same baptismal font that Napoleon had used to baptize his own son, the king of Rome. Yet despite these trappings of imperial grandeur, Lobo had also fiercely opposed the corrupt Batista government. “We didn’t care who overthrew Batista so long as somebody did,” he once said. A receipt nestled among Lobo’s papers and stamped with the swirling red and black Cuban revolutionary logo shows that he had even helped finance Fidel Castro’s rebels a few years earlier. That, however, was before Castro’s plans and eventually his Communist leanings had been fully revealed.

On that October night, as Lobo drove across Havana, less than two years had passed since President Fulgencio Batista had packed his bags on New Year’s Eve and fled to the Dominican Republic, his departure cheered by nearly all. Since then much of Lobo’s land, although not yet his sugar mills, had been confiscated by the rebel leader whom Lobo had once helped. Yet Lobo still refused to leave the island, unlike many other middle- and upper-class Cubans. Nor had Lobo lent his voice to the growing flood of anti-Castro protest. Now Che Guevara was going to put Cuba’s King of Sugar to the test.

LOBO’S CAR TURNED DOWN LINEA and toward the old city. October lies in the middle of the hurricane season, when high sea spray can spume over the broad wall that lines Havana’s waterfront drive, the Malecón. Lobo took this route every day to his office in the old town. The view from his car was little different from that evoked in Graham Greene’s

Our Man in Havana

, published two years before:

Our Man in Havana

, published two years before:

The long city lay spread along the open Atlantic; waves broke over the Avenida de Maceo and minted the windscreens of cars. The pink, grey, yellow pillars of what had once been the aristocratic quarter were eroded like rocks; an ancient coat of arms, smudged and featureless, was set over the doorway of a shabby hotel, and the shutters of a night-club were varnished in bright crude colors to protect them from the wet and salt of the sea. In the west the steel skyscrapers of the new town rose higher than lighthouses.

Yet while Havana looked the same, the atmosphere was quite different from that absorbed by Greene and depicted by his fictional British vacuum cleaner salesman, Wormold. A year ago, Havana was still an exciting city. It boasted casinos, nightclubs, bordellos, and a fabled live sex show popular with tourists in Chinatown’s Shanghai Theater, which featured a performing stud called “Superman.” Drugs such as marijuana and cocaine were freely available. It was Havana’s very seaminess—existing in a parallel universe to Lobo’s world and that of my mother’s parents—that had attracted Greene. “In Batista’s day, I liked the idea that one could obtain anything at will, whether drugs, women or goats,” he wrote.

Indirectly, Lobo himself had been involved in the manufacture of Havana’s steamy nightlife, sensual glamour, and racy reputation. Alongside his other business interests, Lobo had helped finance the Riviera and the Capri, two of the glitziest casino-hotels to open in the 1950s, when Cuba was known as the American Riviera. The latter had a flashy casino and a rooftop swimming pool; the former, a futuristic Y-shaped tower overlooking the sea, was the first major Havana building with central air-conditioning, and had an egg-shaped windowless casino at its heart. Both hotels’ links to the Mafia were an open secret. George Raft, the movie tough guy of the 1930s and ’40s, worked as a greeter at the Capri, glad-handing and joking with customers. Havana’s hotels would later gain further notoriety in the movie

The Godfather: Part II

when one breezy terrace, overlooking the Caribbean, provided the setting for a Mafia birthday party and a famous scene in which sixty-seven-year-old mob leader Hyman Roth carved up his birthday cake—a map of Cuba—for the assembled guests.

The Godfather: Part II

when one breezy terrace, overlooking the Caribbean, provided the setting for a Mafia birthday party and a famous scene in which sixty-seven-year-old mob leader Hyman Roth carved up his birthday cake—a map of Cuba—for the assembled guests.

A grayer and more militaristic mood had fallen over the city since Castro assumed power. The atmosphere was tense with invasion rumors. The purifying uniformity of the revolution that visitors such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir would comment on had started to set in. The days of privilege for Cuba’s upper and middle classes were coming to an end, and increasing numbers were leaving on the ferries and shuttle flights to Miami. As many as sixty thousand had already left by the late spring when the northerly

vientos de cuaresma,

or Lenten winds, would have whipped the bay of Havana into whitecaps, leaving the city feeling airy and fresh and at its most beautiful. Indeed, around that time Lobo had written to a former girlfriend, the daughter of a Danish aristocrat, that her invitation to stay with him remained a standing one. He warned, though, that Havana would not be as pleasant as she remembered. “Gracious living has practically disappeared,” Lobo wrote. “We are entering a period of austerity.” Then he had added the surprising afterthought, “. . . which may have some good points and perhaps even benefits in the long run.” Lobo, the billionaire businessman, could be a revolutionary patriot too.

vientos de cuaresma,

or Lenten winds, would have whipped the bay of Havana into whitecaps, leaving the city feeling airy and fresh and at its most beautiful. Indeed, around that time Lobo had written to a former girlfriend, the daughter of a Danish aristocrat, that her invitation to stay with him remained a standing one. He warned, though, that Havana would not be as pleasant as she remembered. “Gracious living has practically disappeared,” Lobo wrote. “We are entering a period of austerity.” Then he had added the surprising afterthought, “. . . which may have some good points and perhaps even benefits in the long run.” Lobo, the billionaire businessman, could be a revolutionary patriot too.

By October, the roulette wheels were still spinning in Havana’s big hotels, but most of the prostitutes were off the streets and the world of exclusive yachts, private beaches, and casinos had disappeared. Instead, groups of uniformed and armed

guajiros

, poor farmers from the Cuban interior, chanted revolutionary slogans and roamed the streets. In the hotels, trade and cultural delegations from the Soviet bloc took the place of American tourists. Simone de Beauvoir wrote that compared to her visit the year before, there was “less gaiety, less freedom, but much progress on certain fronts.” In the half-empty Hotel Nacional “some very young members of the militia, boys and girls, were holding a conference. On every side, in the streets, the militia was drilling.”

guajiros

, poor farmers from the Cuban interior, chanted revolutionary slogans and roamed the streets. In the hotels, trade and cultural delegations from the Soviet bloc took the place of American tourists. Simone de Beauvoir wrote that compared to her visit the year before, there was “less gaiety, less freedom, but much progress on certain fronts.” In the half-empty Hotel Nacional “some very young members of the militia, boys and girls, were holding a conference. On every side, in the streets, the militia was drilling.”

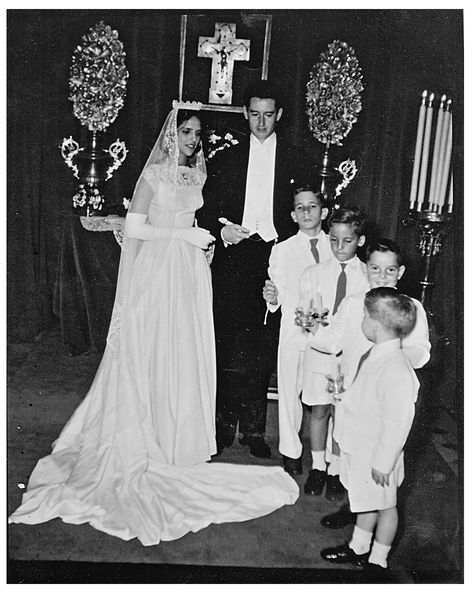

MY MOTHER’S FAMILY, Sanchez y Sanchez, would soon join those sixty thousand Cubans who had already left the island—although my mother had moved abroad several years earlier for reasons that had nothing to do with politics. After the Havana cardinal visited her house to explain why her wedding to an American divorcé the next day had to be broken off, she went to live in New York. There she reveled in the anonymity of a big city, free from what she viewed as the claustrophobia and pettiness of upper-class Havana’s social mores. She got a job as a buyer for the department store Bergdorf Goodman, and met my father, an Englishman, who worked in advertising. They returned to Cuba to get engaged a year and a half before the revolution and were married in Havana on September 3, 1960, just five weeks before Guevara summoned Lobo to his midnight meeting.

In many ways, my mother was typical of her generation, which included Julio Lobo’s younger daughter, María Luisa, one of her circle of closest friends. Like most Cubans, my mother and her family hated the Batista regime. Although she lived a privileged life, she viewed the revolution with excitement. During a trip to the island from New York in early 1959, she turned out, dressed in revolutionary red and black like much of Havana, to watch Castro’s victorious army enter the city.

“Havana was buzzing, there was excitement and hope in the air,” she wrote in her diaries. “The whole country seemed to be behind Fidel. Cuba was free of Batista and all that he represented, we were on our way to true democracy. . . . It was a spectacle that I shall never forget. He and his young bearded men all dressed in battle gear, walking beside their army vehicles, being kissed and hugged by the multitude, red carnations strewn in their path. . . . We were jubilant.”

Wedding of John Rathbone and Margarita Sanchez.

Havana, 1960.

Havana, 1960.

In the following days, my mother watched the televised show trials of Batista’s henchmen, led by Che Guevara, and succumbed to the hypnotic chant of “

¡Paredón! ¡Paredón!,

” “Against the wall! Against the wall!” She felt there was no real difference between a mock and a real trial, as the outcome would have been the same. But my grandfather viewed the proceedings and subsequent firing-squad executions with distaste, and maintained that they marked the beginning of the end.

¡Paredón! ¡Paredón!,

” “Against the wall! Against the wall!” She felt there was no real difference between a mock and a real trial, as the outcome would have been the same. But my grandfather viewed the proceedings and subsequent firing-squad executions with distaste, and maintained that they marked the beginning of the end.

He was right. Much had changed when my mother married my father in Havana eighteen months later. Their wedding was a strange and beautiful occasion, a melancholy mingling of Cuba’s old ways with the uncertainty of the new. The ceremony was held in the family home; the drawing room was converted into a chapel, the arrangements completed with the help of Milagros, Miracles, the firm that traditionally handled Havana high-society weddings. My mother’s nieces acted as flower girls and her nephews walked in front of them dressed in white drill suits, hair slicked into neat partings, carrying lit candles. Only a few people attended, partly because the revolutionary government had banned large private gatherings, partly because most of the people my mother knew had already left the island.

A few weeks later, Castro nationalized my grandfather’s department store on the corner of San Rafael and Amistad streets in central Havana. All of his employees followed him as he was marched out of the shop. They insisted that they would not go back to work without him. But there, in the middle of the street, at the foot of the two-story red art deco building topped with the elegantly silver-lettered name of his business, Sanchez-Mola, he convinced them to return. It would be dangerous not to. Shortly afterward, everyone in my mother’s family—her mother, her father, her sister and brother with their spouses and seven children—packed a suitcase each, took their scrapbooks filled with memories of a life that had already passed, and boarded a scheduled flight for the United States.

LOBO WOULD HAVE KNOWN hundreds of stories like this. Indeed, he had made plans for his own family to emigrate. Leonor, his elder daughter, who was married to a Spaniard, had stayed behind for now, but his younger daughter, María Luisa, with an American husband, had already left.

Lobo’s car pulled up outside the central bank, a columned building on Lamparillo Street in the old city. It lay just three blocks west of Lobo’s sugar trading house, Galbán Lobo, on San Ignacio. This was the nerve center of Lobo’s sugar operation and, lest anyone needed reminding, a huge mural surrounded one of the colonial building’s leafy inner patios. Like the fourteen Stations of the Cross that lined the interior of the baroque cathedral nearby, its 170 square meters of mosaic illustrated key stages of the sugar harvest. From planting to milling, it showed scenes of workers and oxen in the fields under high Cuban skies, all in the elongated and clean art deco style then in favor. In another paean to sugar, Lobo had earlier also commissioned a sugar symphony, and envisaged it beginning with the song of plowmen breaking the earth and ending with the fading sound of sirens as ships carried their cargos of sugar away from Cuba and over the sea.

Other books

Fully Loaded by Blake Crouch, J. A. Konrath

Lauri Robinson by Testing the Lawman's Honor

26 Kisses by Anna Michels

Infinite (Strange and Beautiful, Book 1) by Musick, Brittney

Metamorphosis by A.G. Claymore

Pet Me by Amarinda Jones

The Last Resort by Oliver, Charlotte

Say My Name by J. Kenner

The World: According to Graham by Layne Harper