The Sugar King of Havana (2 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

My mother. Havana, 1955.

Even as a schoolboy growing up in London, I knew that prerevolutionary Cuba with its perfumed waters had indisputable failings. Everyone in 1970s England told me so; the message seemed to be in the very air I breathed. The red double-decker bus that I took to school each day passed a fashionable clothes shop on Kensington High Street called Red or Dead, which later became Che Guevara, and when that shop finally closed down a restaurant opened opposite, called Bar Cuba. Not only was that distant island ruled by one of the world’s longest-serving heads of state—whose accomplishments in health and education I was perforce quick to recognize—everybody seemed to revere him too. It was, in that most characteristic of English emotions, embarrassing. Yet even as a British schoolboy wearing shorts, a cap, and scuffed black shoes, I wondered if Cuba’s failings had been so exceptional as to have nurtured a revolution that had once brought the world to the brink of nuclear war and had dispersed my mother’s family and so many others around the world. It was so at odds with the stories that my mother and her family told me, even though I recognized them as tales of privileged, upper-class Cuban life.

Then I became interested in Julio Lobo. His life and business empire helped shape the troubled years of the Cuban Republic, the very era I was interested in. If any story could reveal how Cuba worked in the prerevolutionary years and disentangle the contradictions that I held inside me, I thought, it would be his. Remarkably, there was no biography. Even the best history books mentioned Lobo only briefly. Such fragments were tantalizing; they suggested a richer and more complicated life, lived on a bigger canvas.

Some writers believed Lobo was Dutch and his name a Hispanicization of “Wolf,” which lent him the ruthless air of a restless egoist, the evil speculator of Communist lore. Others praised his philanthropy. I look at his jowled hound’s face in an old photograph, glowing like white stone, and see the look of a solitary man who loved reading and books. In another I examine his stilled gaze, focused on an event taking place outside the frame. Unfreeze and rewind these single images, though, and Lobo’s life has the explosiveness of a Hollywood movie, one that might have screened in an elegant art deco Havana theater in the days when the city had 135 cinemas—more even than New York. Lobo swam the Mississippi as a young man, fenced in duels, survived assassins’ bullets, was put against the wall to be shot but pardoned at the last moment, courted movie stars, raised a family, made and lost two fortunes, and once told Philippe Pétain, Marshal of France (perhaps apocryphally but also in character),

Je veux dire un mot: merde

, shit.

Je veux dire un mot: merde

, shit.

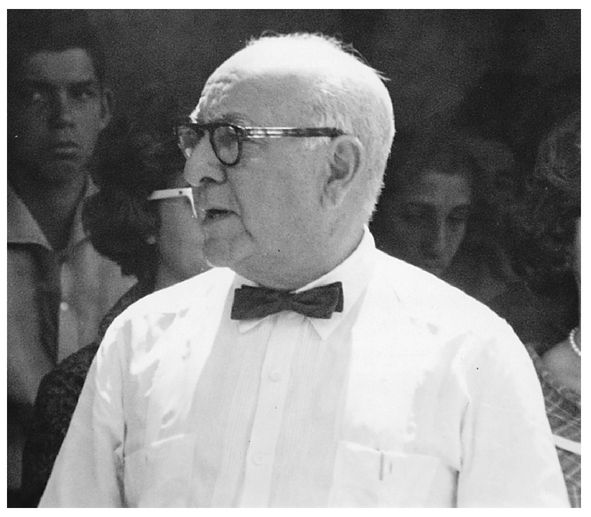

Julio Lobo. Cuba, c. 1956.

More than all this, though, is how Lobo’s life mirrored, in extreme Technicolor, the repeating rises and falls of the Republic. This is more than a literary conceit because Cuba, as is often said, constantly relives its past. Certain events and themes—bewitchment, prosperity, decline, revolution, exile, and return—repeat themselves in recurring cycles that are as old as the island itself. Telling are the first words of the memoir that the Condesa de Merlin, “Cuba’s Scheherazade” and a Havana-born ancestor of Lobo’s first wife, wrote 170 years ago as she watched the island appear on the horizon from the poop deck of her sailing ship: “I am enchanted!” Yet telling too, for me, was the apprehension she felt disembarking again in Havana after a long absence. The condesa, whose father’s house survives in the Plaza del Mercado, worried she might not know the city after living in Paris for forty years. Worse, she feared that it might not know her.

I had held that same fear inside me for many years, teasing away at its anxieties in only a tangential way. After college, I left England and worked as a journalist and economist in Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela. I was searching, of course, for echoes of my mother’s family’s prerevolutionary Cuban past: the music, some of the food, the fast almost slurred Spanish, the mixture of social casualness and Latin formality, the beauty of the mornings before the heat burned away their color, and the unforgettable smell of guavas rotting in the sun that always draws one back to the Caribbean, as Gabriel García Márquez once put it. Yet while I spent a decade living around the Spanish Caribbean, I never visited Cuba. One reason I stayed away from the island, I told myself, was to inoculate myself against tropical lyricism. When I eventually traveled to Cuba, I wanted to be able to see through its vehement sunsets, palm trees, and romantic colonial past in the same way that I wanted to see beyond the glamorous life captured in my mother’s photographs. More important, I avoided Cuba because I feared that I wouldn’t recognize the island from her stories. Worse, I feared that it wouldn’t recognize me.

Finally, I began to make short trips. For a while, in the 1990s, I even ran a newsletter out of a London basement that described the travails of the Cuban economy and what it meant for the island’s future. It was a confusing time. The collapse of the Soviet Union had ended Moscow’s thirty-year patronage of Fidel Castro, and many exiles hoped that his revolution would finally end too. In Miami, expectations swelled of an eventual return and, among the older generations, maybe even something of those glorious prerevolutionary days as well. In Havana, Castro deftly turned those expectations in on themselves. Even as the Cuban ship of state seemed to be sinking beneath him, he conjured up a mythic image of prerevolutionary Cuba, only it was an abject vision rather than golden. There can be no going back, he exhorted.

¡Socialismo o muerte!

¡Socialismo o muerte!

I objected to Fidel; I objected also to the feverish hatred of many exiles’ anti-Castroism. From England, the vehemence of their passions, their bitterness and rage, sometimes had the feeling of a flat-earth society. Publishing the newsletter, I became briefly what others called an expert. I gave talks in Europe and the United States, at universities and in government departments. Yet the more expert I became, the less truth I recognized in much of what I read or heard. Even the best commentary from the island was driven by a government-sponsored sleuthing that aimed to uncover a malignant force—usually capitalism. Yet neither did I recognize a rounded picture in the sugar-coated memories told to me in Miami. In time I came to see that exile imposed a kind of selective censorship, a critical numbing that might otherwise tarnish glorious memories, which can be all that is left when everything else is taken away.

When I began to write this book, Castro was still strong enough to stand in the midday sun and give two-hour-long speeches. As I finished it, he had vanished from view, suffering from a severe intestinal disorder, having handed power over to his then seventy-six-year-old younger brother, Raúl. “The Revolution is stronger than ever,” Raúl had proclaimed in 2009 on the occasion of the revolution’s fiftieth anniversary. “Glory to our heroes and martyrs.” News photographs of the event showed Raúl dressed in military uniform, addressing an invited audience of elderly army officers under the hot Caribbean sun. It was a significant symmetry: half a century before, a young and charismatic lawyer, Fidel Castro, had taken power in Havana, displacing a corrupt dictator, while an old general, President Eisenhower, sat in the White House. Now, fifty years later, a young, charismatic, and black lawyer was in the White House, while an aging white general, Raúl, sought to maintain the dream of a flawed revolution in Cuba.

Far too much, whole libraries, has already been written about the revolution. As the island limps toward the end of the Castro brothers’ rule, what interests me more are the events, some of them very distant, that preceded and caused it. A famous historian once suggested to me that recovering a better knowledge of this history could play as crucial a role in the country’s future as it did in Russia before the fall of the Soviet Union. If so, thinking about Cuba’s “before,” therefore, also meant thinking about its “after.” In Havana, a wise friend counseled me that this was a vain and preposterous task. Better, he said, to ponder something else, as so many people had been proven so wrong over so many years. I took only half his advice, though, as it is impossible not to wonder about Cuba’s future, even if I have done so through the lens of its past.

I think of a speech that Winston Churchill gave in the House of Commons when Neville Chamberlain died in 1940. The great British wartime prime minister—who first saw action in Cuba as a young man, where he began to smoke large cigars—described to Parliament how history, “with its flickering lamp, stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days.” So it is that my concern here is with the flickering myths, untold stories, and simple facts that surround the life and businesses of Cuba’s once-richest man, Julio Lobo, and the Cuba in which he lived. Sometimes I have turned to my mother’s family to help reveal these half-hidden times. This is not out of any sense of vanity. Rather it is because they also played a small but not always insignificant part in helping shape a prerevolutionary way of life that supposedly heaped so many inequities on the island that civil war, the exile of a tenth of the population, and the enduring struggle of those who remained were somehow inevitable. Shrunken, their stories form part of a calumnious revolutionary narrative that diminishes prerevolutionary Cuba’s past—sometimes inglorious, sometimes the opposite. Expanded and brought back to life, they also suggest happier futures.

PART ONE

One

A TRISTE TROPICAL TRYST

There’s a violent smell of sugar in the air.

—AGUSTÍN ACOSTA,

La Zafra

La Zafra

O

n October 11, 1960, Ernesto “Che” Guevara summoned the sugar magnate Julio Lobo to his office at the Cuban central bank in Havana. It would be a midnight meeting—odd, but not entirely unusual during those chaotic times. The Cuban revolution was barely eighteen months old, an inexperienced government was remaking the island, and, anyway, Guevara often worked through the night, if only to keep up with events and as an example of his iron will and revolutionary discipline. Stories abounded in Havana of foreign dignitaries turning up at the central bank for a meeting at three o’clock in the afternoon, only to be told that their appointment was at three in the morning.

n October 11, 1960, Ernesto “Che” Guevara summoned the sugar magnate Julio Lobo to his office at the Cuban central bank in Havana. It would be a midnight meeting—odd, but not entirely unusual during those chaotic times. The Cuban revolution was barely eighteen months old, an inexperienced government was remaking the island, and, anyway, Guevara often worked through the night, if only to keep up with events and as an example of his iron will and revolutionary discipline. Stories abounded in Havana of foreign dignitaries turning up at the central bank for a meeting at three o’clock in the afternoon, only to be told that their appointment was at three in the morning.

Lobo hastily called his lawyer and consigliere, Enrique León. “Che wants to see me,” he said, and hung up the phone. León arrived shortly after at Lobo’s neoclassical mansion in Vedado, a residential area west of the old city. The two men conferred briefly in the hallway and then left in Lobo’s car, driving east through the Havana night.

Lobo sat behind the wheel of the humming black Chrysler, his lawyer by his side, the car headlamps picking out a few sudden faces on dark street corners. Curiously, in letters written a few months earlier, Lobo had often depicted himself driving a machine. Sometimes it was a vast ship, Lobo the captain on the bridge, confidently guiding his empire through the rough waters of revolution toward a safe harbor. “We are going through very difficult times, though I am a confirmed optimist,” he wrote in one letter. Yet just as often the machine was a more modest contraption. “I often feel like a man on a bicycle: if I stop, I will fall. . . . I am quite incorrigible and in a way irrepressible,” he wrote in another. There is a sly humor to these words, a quiet, self-confident gloss, which suggests that when Lobo drove to meet Comandante Guevara that evening he was resolute, hopeful, perhaps deluded about what would happen, but certainly not scared. Fearful was not Lobo’s style.

Other books

Rocking Horse Road by Nixon, Carl

Senescence (Jezebel's Ladder Book 5) by Scott Rhine

A Short Stay in Hell by Steven L. Peck

The Life of the World to Come by Kage Baker

Gavin's Death (Cara Daniels Cozy Mystery Book 4) by Gillian Larkin

A March of Kings by Morgan Rice

A Game of Sorrows by S. G. MacLean

Controlled in the Market by Fiora Greene