The Suitors (21 page)

Authors: Cecile David-Weill

Now that a real estate agent had turned up, however, my parents’ idea had become a project they might just carry out. Even so, I still had trouble considering all its implications, as if the entire business were frankly unreal, like a sudden death. As if I could no longer feel what

I knew and know what I felt. Which was why I kept telling myself, “They did it, I don’t believe it.”

I was in shock, chain smoking as I wondered if I should awaken Marie to break the news to her, when I noticed that Félix had tried several times to reach me on my cell phone. The message he’d left said nothing about why he’d been so eager to reach me, which left me high and dry, especially since he did say specifically that I would have no way of getting in touch with him before the next day. My throat tightened with anxiety.

So I was understandably light-years away from Béno Grunwald when my mother rang me in my room.

“I’m told your guests are wandering around the house. Really, you might pay some attention to them!”

Béno, Mathias, and Lou were indeed drifting on their own in the front hall of a house left to its own devices while the secretary and butlers were busy confessing their blunders to my mother, but it didn’t take me long to show the guests to their rooms, tell them when dinner would be served, and notice that Béno bore a slight resemblance to Steve McQueen. A dreamboat, this guy, I mused, and tried to stop worrying about my son, who kept interfering with my thoughts.

News of Béno’s misadventure had made the rounds of the house before cocktail time, but that didn’t stop

him from stealing the limelight from Mathias and Lou Léva, who paled in comparison when he gave a hilarious account of the fiasco.

Béno may have been a dazzler, but he still set out to win over everyone in sight, as if he’d had a handicap or something to make up for. He began with my mother, whom he captivated in record time. To begin with, he had the good taste not to mention his helicopter trip, plus he brought her the ideal gift: a hundred matchbooks engraved with the name of L’Agapanthe. He then deployed in her direction a panoply of attentions between flirting and deference, by rising to his feet the moment she seemed about to move elsewhere in the room, by praising her voice (“You’ve never thought about a career in radio?”), and by flashing her a radiant smile whenever she spoke to him. Next he tackled my father, to whom he pledged allegiance with a few words over an apéritif: a modest and convincing spiel about his hedge fund, followed by a request for a five minute tête-à-tête sometime that weekend for a few words of advice—and that was that.

For his finale, Béno sent us all into stitches by making fun of his family’s embarrassment over the original recipe for that photographic gelatin, which turned out to be made with bones from India. “Okay, fine, sometimes

there were a few femurs,” admitted his mother. And he didn’t spare himself, allowing that his expensive habits were such that he’d really had no choice but to make a fortune. He’d studied up on his Cap d’Antibes history, too, and was abreast of all the latest juicy inside scoops.

Béno commanded so much attention that Mathias attracted very little in spite of his glaring blunders, which were legion. With striking linguistic ineptitude, he proudly claimed to have been the “investigator” of my encounter with Béno, and he introduced Lou to my parents as an actress “destinated” for a great future. With a flourish, he then produced his gift, a particularly garish scarf, which he presented to my mother who, although she had an absolute horror of designer logos, nevertheless went into ecstasies with professional aplomb over the entwined pink and blue initials that formed the sole decorative pattern of her gift.

Nothing, as it happened, was more vulgar in my parents’ eyes than

luxury brands

, two words they considered a perfect oxymoron. The offspring of marketing and manufacturing,

brands

—Walmart, H&M, Monoprix, Zara—were used to put objects within the reach of everyone, whereas luxury implied the made-to-measure expertise of craftsmen skilled at rendering material goods worthy of interest. Which ruled out any desire to possess

the latest accessory

de chez

Dior, Vuitton, or Prada, an ambition my parents found as pointlessly petit bourgeois as going into raptures over the purchase of an ice-cream maker or a fondue set.

When Lou Léva made her appearance at cocktail time, I felt a ripple of disappointment pass through every man present. The gentlemen had doubtless envisioned some sexy creature, bold as brass, and had hoped to find the actress dripping with sensuality à la Marilyn Monroe, a girl whose heart would belong to daddy. Instead of which, in walked a thin, pale young woman who rather disappointingly resembled an orchid: exotic, true, but somewhat off-putting. With short black hair, a hank of which fell across one side of her face (when it wasn’t held back by a girlish barrette), she was pretty, but in an ethereal way. She might even have been touching, if she hadn’t affected a fragile and sorrowful air she hoped might lend her some gravitas, for she thought that sadness was chic.

Lou seemed to have stopped short of achieving the desired level of soigné manners, however, for she approached my mother with an utterly unchic, “Come on, let’s kiss-kiss-kiss.”

A greeting devoid of elegance, from the appallingly informal “Come on” to the grotesque “kiss-kiss-kiss,”

not to mention the excessive familiarity toward my mother, whose customary welcome was a genteel nod or, at most, a handshake. As for triple cheek kisses, nothing was more provincial.

For everyone in France should know by now that Parisians give only two pecks on the cheeks, unlike the rest of the country, where regional differences gave rise to all sorts of variations with three or even four kisses, to which the average Parisian good-naturedly adapts by attempting to imitate an embrace of unknown rhythm and duration, like a beginning dancer following the lead of an experienced partner.

Then, when the butler announced that dinner was served, Lou exclaimed with a shriek, “I’m starving! I haven’t had a bite since noon!”

This was another botch, since she should not have used the slangy “a bite” so baldly.

In short, Lou was not one of us, because she was unable to grasp the subtleties of our particular jargon, a fact that we initiates—who recognize one another, like freemasons of refinement—noticed immediately, without comment, but did not dismiss. And we had every right to hold it against her, strange though that might appear, for fewer and fewer people still understood what we were talking about when we talked about such things.

MENU

Oeufs à la Chartres

Dorade Royale

Potato Purée

Salad and Cheeses

Green Apple and Cinnamon Ice Cream

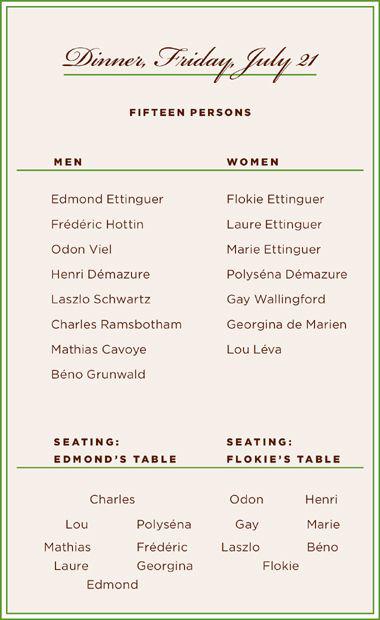

Seated next to Charles Ramsbotham, Lou quickly struck up a conversation.

“I believe I heard that you were English. How come you speak French so well?”

“My mother was Swiss and silent,” intoned Charles in a sinister voice that did not discourage Lou in the least.

“Are you married?”

“Yes.”

“Why didn’t you bring your wife with you?”

“Because she is boring.”

Charles’s reply happened to fall loudly into one of those unexpected moments of silence that occur during conversations, and so, after a moment of astonishment, our table collapsed into hilarity in spite of my father’s attempts to restore order. After all, none of us had seen

Lady Sally for years because, like an exotic fruit, she did not travel well, given that she cared only—in order of importance—for white wine, gardens, dogs, and horses.

Georgina came nimbly to the rescue. “Edmond, these oeufs à la Chartres are heavenly, perfectly poached and with

just

enough tarragon. I’m tempted to have more, but that depends on the main course. What will come next?”

“I was wondering the same thing,” added Frédéric. “This sauce is to die for. What is it? Madeira? Veal stock?”

“Help me out, Marcel,” said my father, turning toward the butler. “I’ve no idea what to tell them …”

“Veal stock, Monsieur. And the next course will be dorade, and for dessert, ice cream, I’ll have to inquire about the flavor.”

The episode with the real estate agent had so shaken me that I didn’t feel up to helping my father with his duties as host, and I left the handling of table conversation completely to him. Art was often the chief topic of our dining discussions, and it cropped up all the sooner in this case since Mathias spoke right up in his capacity as a dealer, thus proving he was keeping his eye on the prize.

“Do you buy much?” he asked my father.

While I was guessing whether Mathias would have the nerve to try selling him something before dinner

was over, Polyséna began deploring the contamination of the art market by money.

“Money as pollutant, or money as patronage, it’s a classic debate,” my father told her.

In his eyes, Polyséna’s besetting and inconvenient sin was to be both intoxicated by her own learning and stuffed with opinions so conventional that she became the very caricature of a pedant, so my father couldn’t help condescending to her slightly when he focused the argument on money as the sole common denominator of our fragmented societies, and the trendsetter henceforth of an artistic taste forged in the past by European courtly life. Vexed at being caught

en flagrant délit de cliché

, Polyséna played her trump card, making a daring rapprochement between a Renaissance painter and Damien Hirst in a bold attempt to leave my father speechless.

Frédéric, who had no particular desire to take part again in another discussion on art, turned quietly to Georgina. “So, it seems you live like a deluxe nomad …”

Georgina countered by observing that travel gave her the impression of making some progress. At first, lost in a new city and sometimes even unable to speak the language there, she would feel alone and disoriented, but since she thus had every reason to feel bad, this dispensed with the need to ask herself existential

questions and brood over the latent depression that plagued her. Besides, the challenge of establishing herself in a strange place made her feel brave, adventurous, even heroic. And that persuaded her to accept the austerity of her life while awaiting the blossoming of her adjustment to her new home.

I was overhearing Georgina while listening to Polyséna as she developed her theory.

“It was largely for his contacts that Cosimo I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, hired Vasari in 1555 to decorate the interior of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, which displayed works by Michelangelo, Leonardo, Pontormo, and Il Rosso. Why Vasari? Because, like Damien Hirst, he was professionally and socially ambitious. He lacked originality but displayed sound judgment formed by the cultivation of his peers and the demands of his patrons, as well as the genius of the zeitgeist, the mood of the times, which he caught like no one else.”

Uncommitted, I couldn’t manage to become engrossed in either of these conversations, so I decided to amuse myself by both following the story of Georgina’s peregrinations

and

keeping an expression of rapt enchantment turned toward Vasari, thus learning how hard it was to listen to a conversation without watching the person speaking!