Read The Super Mental Training Book Online

Authors: Robert K. Stevenson

Tags: #mental training for athletes and sports; hypnosis; visualization; self-hypnosis; yoga; biofeedback; imagery; Olympics; golf; basketball; football; baseball; tennis; boxing; swimming; weightlifting; running; track and field

The Super Mental Training Book (28 page)

I wish to highlight as well Russ Knipp's remark that he "concentrated on one focal point" whenever he hypnotized himself. Such concentration is quite helpful—some experts say necessary—for one to attain the hypnotic state. For example, Dr. William J. Bryan, in his Legal Aspects of Hypnosis, states this:

Weightlifting

111

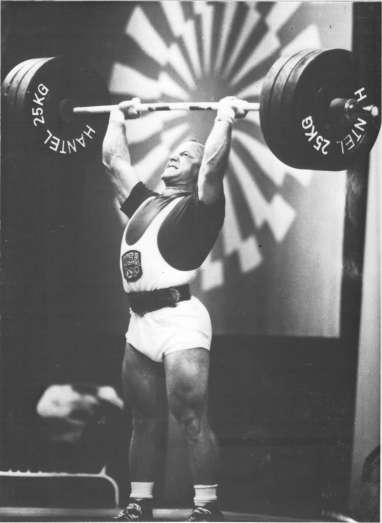

Using principles of self-hypnosis, Russ Knipp lifted a world record of 369 pounds in the press during the 1972 Munich Olympics. Here is that record lift.

Every hypnosis induction contains two things regardless of how you induce a person. One, a central focus of attention; two, surrounding areas of inhibition in the cerebral cortex. If those two things are present, the person may enter the hypnotic trance.

Knipp's central focus of attention was his midsection. He concentrated on it, claiming that "the power of your strength comes from the midsection." Interestingly, this contention of Knipp's is in direct agreement with what practitioners of the martial arts maintain (see the discussion of chi and the tan tien in the Amateur Athletes chapter).

When I talked to Knipp, I wanted to obtain his opinion of a comment made by Dr. Warren R. Johnson, who stated in his paper, "Hypnosis and Muscular Endurance," the following:

My experience has led me to suspect that hypnotic suggestions are more likely to improve the strength performance of nonathletes than of athletes; and conversely, that hypnotic suggestions are more likely to improve the endurance performance of athletes than nonathletes. [2]

A champion weight lifter who regularly practiced self-hypnosis for years, such as Russ Knipp, should be qualified to discuss this question. So, I asked Knipp what he thought of Dr. Johnson's opinion. The thrust of the answer he gave me is that even if hypnosis provides only small improvements in an athlete's strength and endurance, that can prove sufficient to make the difference between victory and defeat. Explained Knipp:

Lifting is probably fifteen to twenty percent endurance. I know guys that are physical wrecks in endurance or stamina, but can lift phenomenal tonnages. They couldn't run down the street if they had to.

But, here's the thing. In any sport, if you take a highly-conditioned athlete, to make him improve just five percent or three percent is a drastic improvement. But, take a beginner who doesn't know how to do anything right. He could throw a shot, for example; now, you hypnotize him and have him throw a shot again. Under that psych he can do amazing things. But, an experienced athlete is working more towards his potential. To get an extra four inches on a top shotputter, you're talking a lot. Because that's the equivalent to maybe ten inches for a beginner.

Coincidentally enough, Knipp once hypnotized a beginner weight lifter. Although a beginner, he was not a nonathlete. However, just as Dr. Johnson speculated about nonathletes, the beginner's strength performance improved dramatically. Knipp tells what happened:

I saw thirty pounds lifted above what a lifter ever lifted before. He was again just a beginner. I worked with this young lifter for about three weeks, just doing different things: autosuggestions and power suggestions. In one workout, I hypnotized him. It was late at night, nobody else around. I had him go out, and the kid broke thirty pounds over his best in the clean. This occurred in Pittsburgh about two years after I graduated from high school.

Another weight lifter, Marshall Morris, used self-hypnosis to substantially improve his strength performance. Morris learned self-hypnosis from me in 1978, and employed it regularly afterwards for competitions. In January, 1980 he set a National Junior weightlifting record for the snatch in the 165-pound class, lifting 130.5 kilos (288 pounds); Morris was 19 years old when he set this record. A disastrous performance at a weightlifting competition had prompted him to come to me for help. Recalled Morris, "I had just bombed in the snatch in a Junior Olympic meet, lifting only 90 kilos (198 pounds). I came over to your [the author's] house, learned self-hypnosis, and went to the Fullerton College weight room. There I snatched 110 kilos (242 pounds). So, that just shows you how much your mind controls everything."

Morris used self-hypnosis in a different way from Russ Knipp; he preferred a conditioned-response and visualization approach:

I really get into a good hypnotic state when I'm warming up with light weights (30 to 40 percent of my max). I try to feel my whole body while warming up. I also try to get my hand-eye coordination down, since Olympic lifting is so technical. I think about keeping my body tight, extending, and jumping up with the weight. But, you can't really think about all that stuff, especially when the weight gets heavier; that's why I try to feel my whole body while warming up with the light weights, so that my motor-nerve pattern knows what to do.

To enter the hypnotic state, said Morris, "I don't have to lie down." Instead, he developed the instant self-hypnosis capability, and put it to use while warming up. Morris also found no place for relaxation in his self-hypnosis regimen. "If I relax my mind," he noted, "I'll relax my body— and that's what I don't want. I stay pretty well tensed up, because you have to think about attacking the bar, not be afraid of it."

Morris captured the 165-pound class championship in the U.S. National Junior Olympics competition in July, 1979; in fact, he outlifted the winners of the 181-lb., 198-lb., 220-lb., and 242-lb. classes. Hard physical training and proper mental training paid off for him. His positive experience with self-hypnosis while competing as a junior led him to recommend the technique to other junior athletes. Observed Morris, "I think it's good for junior athletes to use self-hypnosis early, so that by the time they are older, it will be a natural thing. For example, I see a lot of junior lifters go into the weight room with their radios playing; they socialize half the time, instead of really training. You can't go into the weight room with your mind off somewhere else."

Yet another weightlifting record was broken with the assistance of hypnosis. Los Angeles Times writer Pete Thomas reported that Fred Hatfield, editor of Sports Fitness magazine, was helped by hypnotist Peter Siegel in setting "the world power-lifting squat record at 1,008 pounds, more than four times his (Hatfield's) body weight."[3] Remarked Hatfield, "That's a pretty intimidating weight for anybody. There is no doubt in my mind it (the successful lift) came from Peter's therapy. Peter has a unique talent which goes far beyond that of sports psychology."

Siegel, whose relationship with New York Mets pitcher Sid Fernandez we noted in the Baseball chapter, discussed with Thomas the purpose of the hypnosis sessions he holds with his athlete-clients:

To shake up the mind in order to dislodge that mental block holding an athlete back. I help them mobilize the seed of their power. I help them get to the essential point of their ability to express peak athletic performance, and help them become regulators of that ability.

I make sure the power of the mind works in conjunction with the power of the body. Thought is to the mind what food is to the body.

Terry McCormick, former U.S. and world powerlifting champion, also has testified to the value of hypnosis, and, in more ways than one, is a "strong advocate" of the technique. He was asked by Orange County Register sports columnist Cliff Coan this question: "Did you do anything differently or acquire any special knowledge that enabled you to become a world champion?" Replied McCormick:

Two things proved to be invaluable, both in my training and in competition. Having a complete knowledge of bio-mechanics was one... The other was hypnosis, including self-hypnosis and hypnosis with the help of a psychotherapist. This was a field that I helped pioneer in this sport.

Once I was certain that I was in peak condition for competing, I then conditioned myself mentally that I would accomplish each lift successfully.

By using hypnosis, it was possible to feed positive facts to my subconscious mind. Positive in, positive out. Seeing the hundreds of pounds of iron in front of you, that you are going to attempt to lift, can be awfully intimidating if you are not mentally prepared. In your mind, you have to be completely convinced that you will successfully lift all that iron, or your chance of being successful is practically nil. [4]

McCormick then offered advice for those just starting out in powerlifting, two suggestions being "develop the ability of complete concentration," and "check your attitude as you walk into a gym and make sure it is positive;" mastery and regular practice of self-hypnosis would seem to fill the bill in this case, as it has with many champion lifters.

Not surprisingly, some individuals involved in the world of weightlifting have experimented with other mental training strategies besides hypnosis and visualization. In 1983, for example, Michael Mahoney of Penn State University tried out some simulation techniques on top American weight lifters—athletes considered good bets to make the U.S. Olympic team. This took place at a training camp, with Mahoney devising in one instance a simulation of competitive conditions the lifters might encounter in the Olympics. The athletes were subjected to all sorts of distractions while attempting their lifts—camera flashbulbs popping, spectators cursing them, etc. The aim of all this, as L. A. Times reporter Beth Ann Krier related, was "to teach the weight lifters to remain calm and focused on the task immediately before them—despite distractions of any sort."[5] Whether Mahoney succeeded in his efforts we gain no clue from Krier. We do know, though, how the U.S. lifters, fared in the '84 Olympics: they won 1 silver and 1 bronze medal out of 10 separate weightlifting events (30 total medals awarded). However, if the Bulgarian, East German and Soviet weight lifters had competed (the Soviet Union and most Eastern European nations boycotted the '84 Olympics), it is doubtful that any U.S. weight lifter would have won a medal.

Most assuredly, the Soviet weight lifters, had they participated in the '84 Olympics, would have done extremely well. Weightlifting is taken very seriously in the USSR. International class weight lifters there reportedly engage in intense mental training, besides carrying out their grueling physical workouts. [6] Russ Knipp, for example, informs us that "every Russian Olympic athlete takes classes in hypnosis." It is difficult to determine if this statement holds true for every Soviet Olympic athlete; but, based on a wide range of evidence, very conceivably all Soviet Olympic team weight lifters employ mental rehearsal techniques for training and competition.

Knipp says he talked to the Soviet weight lifters, and they acknowledged that they have classes and sessions in hypnosis:

I've talked to different Russian athletes. They have (hypnosis) sessions. The Bulgarians, for example; they'll have classes, and do different things to make the athletes relax. They use music as one form of concentration; they'll also use total darkness.

Naturally, if the Soviet and Bulgarian weight lifters were to admit to using hypnosis, it makes sense that they would tell a fellow champion athlete such as Russ Knipp, with whom they have a lot in common. I asked Knipp if the Soviet athletes talked freely on the subject to him. He not only answered affirmatively, but provided some eye-opening information about Soviet champion David Rigert, who set 64 world records during his career and was considered at the time the world's best weight lifter, pound for pound:

Oh sure. For example, Rigert spoke. He said he was a very good subject in hypnosis, and had a very high belief factor. Rigert said he personally could not believe he could train as hard as he did and lift those kind of weights in training. He said a transition took place in his life from 1970 to 1971, and it was hypnosis that brought him into

a new realm of lifting. His workload doubled. He was working out so hard, he just didn't know how his body would stand up under the strain. Rigert said it was hypnosis that helped him.

If you ever witnessed David Rigert compete, you might have observed that he appeared to be using self-hypnosis. What he did before attempting the lift was to: 1) totally relax his body, 2) close his eyes while tilting his head back, and 3) take deep breaths. This is the procedure Rigert followed during the 2nd Annual International Record Makers competition held in Las Vegas in August, 1978. It is likely Rigert gave himself reinforcing suggestions right before attempting the lift; or, during this time he might have been visualizing the lift, mentally seeing himself employing proper form in hoisting the weight. Whatever the case, Rigert broke two more world records during the Las Vegas competition. Over a 10-year span he destroyed the record books in the mid-dleheavyweight class, the class in which he was the 1976 Olympic champion. For the Las Vegas meet Rigert moved up to the heavier 220-pound division. Lifting a total of 870 3/4 pounds he set new records in this division, too! Such feats hardly seem possible; and, as Knipp relates, even Rigert "could not believe he could train as hard as he did and lift those kind of weights in training." But, "it was hypnosis that brought him into a new realm of lifting."

Rigert trained as hard mentally as he did physically. This is evidenced by the response Los Angeles Times writer Bill Shirley received when he asked the Soviet champion why weight lifters stare so long as the bar before attempting to lift it: