The Sword And The Olive (37 page)

Read The Sword And The Olive Online

Authors: Martin van Creveld

On the afternoon of June 5, after several hours trying to bring about a cease-fire, Israel and the IDF had had enough antics from the “little king.” The IAF went into action, wiping out Jordan’s small air force (they had one radar station) in its bases, also paying a visit to the old, British-built H-3 air base in western Iraq; when the balance of the first day’s fighting was summed up on the radio late that night, the IAF could boast of having destroyed no fewer than four hundred Arab aircraft in all. Meanwhile a crack brigade of Israeli paratroopers (the 55th) had been standing ready to take Al Arish in conjunction with Tal’s forces. When that town fell ahead of time, the brigade was diverted to confront the Jordanians.

To the south of Jerusalem, Narkis’s Jerusalem Brigade was holding on to the area around UN headquarters while the paratroopers of Mordechai Gur—he had entered Mitla Pass in 1956—prepared to envelop the city from the north.

30

Late that night, the paratroopers fought an extremely tough engagement in a fortified area known as Ammunition Hill overlooking the road from West Jerusalem to Mount Scopus and Mount Olives. When the latter fell, the Jordanians in East Jerusalem found themselves encircled. Moreover, since the main highway runs through town, communication between the two main parts of the West Bank—the northern and the southern—had also been cut.

30

Late that night, the paratroopers fought an extremely tough engagement in a fortified area known as Ammunition Hill overlooking the road from West Jerusalem to Mount Scopus and Mount Olives. When the latter fell, the Jordanians in East Jerusalem found themselves encircled. Moreover, since the main highway runs through town, communication between the two main parts of the West Bank—the northern and the southern—had also been cut.

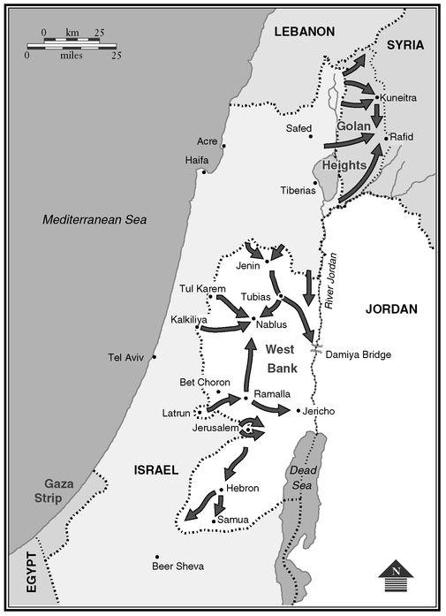

MAP 11.2 THE 1967 WAR, JORDANIAN AND SYRIAN FRONTS

That same evening (June 5) another mechanized brigade belonging to Central Command drove up the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway. Before reaching Mount Kastel they turned north, however, using a dirt road that ran parallel to the highway. Although the topography was the same, this time there could be no question of the Israelis attacking mainly with light arms, as Rabin’s men had done in 1948; instead they used their Super Sherman tanks in close support, quickly breaking through several defended Arab positions before debouching at Tel Ful north of Jerusalem on the morning of June 6. As a third brigade reached Ramalla, farther north, by way of Latrun and Bet Choron, there were now no fewer than three IDF brigades stationed along the north-south watershed and cutting the West Bank in half. Any hope that the situation might still change was soon ended. With its hands freed by the destruction of the Arab air forces the previous day, the IAF intercepted Jordanian 60th Armored Brigade on the road from Jericho—where burned-out tanks and other armored vehicles could be seen strewn about for years to come.

On June 7 the great drama was complete. Jerusalem Brigade turned south, driving toward Hebron and sending the Jordanian brigade deployed around the city—they had been sent in hope of linking up with the Egyptians!

31

—into a hasty retreat. Gur’s paratroopers broke through Jerusalem’s Lions’ Gate and were soon mopping up in the Old City; of Narkis’s two mechanized brigades stationed on the Jerusalem-Ramalla Road, one took the old road toward the Jordan Valley and Jericho, whereas the other turned north to link up with the forces of Brigadier General Peled

.

That

ugda

had been engaged in heavy fighting since the afternoon of June 5. One armored battalion drove down to Bet Shean, from where it probed the Jordanian part of the Jordan Valley from the north, thus threatening to take 40th Armored Brigade in the rear. Three brigades (one minus a battalion) converged on Jenin. Farther southwest, Narkis’s 5th Brigade entered the West Bank by a different road and made directly toward Nablus.

31

—into a hasty retreat. Gur’s paratroopers broke through Jerusalem’s Lions’ Gate and were soon mopping up in the Old City; of Narkis’s two mechanized brigades stationed on the Jerusalem-Ramalla Road, one took the old road toward the Jordan Valley and Jericho, whereas the other turned north to link up with the forces of Brigadier General Peled

.

That

ugda

had been engaged in heavy fighting since the afternoon of June 5. One armored battalion drove down to Bet Shean, from where it probed the Jordanian part of the Jordan Valley from the north, thus threatening to take 40th Armored Brigade in the rear. Three brigades (one minus a battalion) converged on Jenin. Farther southwest, Narkis’s 5th Brigade entered the West Bank by a different road and made directly toward Nablus.

To defend the area in question the Jordanians had three infantry brigades plus the elite 40th Armored Brigade, which, disregarding the threat to its communications, moved up to Jenin by way of Tubias on June 6, meaning that the two sides were approximately equal in numbers. Riding dissimilar vehicles—the Israelis relied on their Super Shermans and half-tracks, the Jordanians on M-47s, M-48s, and M-113 armored personnel carriers (APCs)—they slugged it out at close quarters among the narrow mountain valleys. Israeli accounts emphasize the excellence of the Jordanian troops so long as they stayed put and were not called upon to counterattack;

32

per Jordanian accounts, the decisive nature of the air strikes rained down on their “hapless” troops.

33

Hitting fortified positions located on mountain slopes from the air with the equipment then used by the IAF—they wouldn’t deploy precision-guided munitions (PGMs) and computerized navigation attack avionics till later—is difficult even for the best pilots. Perhaps, then, the two accounts can be made to dovetail by assuming that the Jordanian counterattacks failed

because

whenever their armor broke camouflage and got moving it would come under air attack.

32

per Jordanian accounts, the decisive nature of the air strikes rained down on their “hapless” troops.

33

Hitting fortified positions located on mountain slopes from the air with the equipment then used by the IAF—they wouldn’t deploy precision-guided munitions (PGMs) and computerized navigation attack avionics till later—is difficult even for the best pilots. Perhaps, then, the two accounts can be made to dovetail by assuming that the Jordanian counterattacks failed

because

whenever their armor broke camouflage and got moving it would come under air attack.

Be that as it may, after thirty-six hours of tough fighting the Israelis prevailed. By the evening of June 7 their right-wing brigade had crossed through Nablus (where they were initially mistaken for Iraqis and welcomed by the population) and linked up with the one coming up from Jerusalem. The other three took Jenin and proceeded south and east, occupying the Jordan Valley and blocking the escape routes of whatever Jordanian units had remained intact. Though the Arab Legion fought well, its forces had been shattered, and only stragglers made it across the river; the Israelis, who also had a vast stream of refugees on their hands, did not try to stop them so long as they left their arms behind. In the confusion one of Narkis’s brigades had actually crossed to the East Bank without orders.

34

According to Rabin, he learned of the move only when the United States, prompted by Hussein, ordered Israel to desist.

35

Thereupon the 10th Brigade, having crossed into the East Bank, was told to retreat and did so, blowing up the bridges as it went.

34

According to Rabin, he learned of the move only when the United States, prompted by Hussein, ordered Israel to desist.

35

Thereupon the 10th Brigade, having crossed into the East Bank, was told to retreat and did so, blowing up the bridges as it went.

It remained to deal with the Syrians, who, in contrast to their bellicose actions during the years leading up to the war, scarcely lifted a finger while their allies were being pulverized. On June 6 and 7 they fired at the settlements in the Jordan Valley, inflicting considerable material damage (“205 houses, 9 chicken-coops, 2 tractor-sheds, 3 clubs, 1 dining hall, 6 haystacks, 30 tractors, 15 cars”

36

according to a meticulous Israeli account) but killing no more than two and wounding sixteen. What offensive plans they may have had never materialized; at any rate any talk of an offensive was absurd, given that by the evening of June 6 most of their air force had been destroyed by the IAF. Israel and the IDF, however, were bent on revenge against the Syrians, whom they regarded as the most implacable enemy of all.

36

according to a meticulous Israeli account) but killing no more than two and wounding sixteen. What offensive plans they may have had never materialized; at any rate any talk of an offensive was absurd, given that by the evening of June 6 most of their air force had been destroyed by the IAF. Israel and the IDF, however, were bent on revenge against the Syrians, whom they regarded as the most implacable enemy of all.

Relying on the excellent intelligence on the Golan fortifications provided by spy Eli Cohen prior to the war, Northern Command drafted several plans for dealing with the Syrians. Thus “Makevet (Sledgehammer) North” provided an offensive against the northern part of the heights; “Makevet South” for an attack on the center; and “Makevet Center” for a purely holding operation. Once the war had started and a decision had to be made, however, the Eshkol-Dayan-Rabin-Bar Lev (Rabin’s deputy)-Elazar chain of command proved less than perfect. At first, on June 6, Elazar was given permission to attack on the next afternoon. Next, waiting for reinforcements—he had only two brigades left, having lost one to the West Bank—and for the sky to clear, he decided to postpone for twenty-four hours. Around noon on June 7 Bar Lev was still telling him to go ahead; but at 1000 hours on June 8 Rabin came on the phone and informed his front commander that the IDF “did not have permission” to attack.

37

37

Flying to Tel Aviv, an outraged Elazar met with Eshkol (for some reason all the prime minister’s secretaries had disappeared and his wife was answering the telephone); unable to change his mind, he went back to his command post. That same evening a Cabinet meeting was held and Dayan, seeking to restrain the aggressive tendencies of Rabin, Allon, and Eshkol himself, explained his reasoning. The war against Egypt was not yet over; the Soviets were making threatening noises and might intervene; the Israeli canary had swallowed two cats—Egypt and Jordan—enough of a meal even without also adding Syria.

38

That night, however, Dayan changed his mind. As he later explained, the Egyptians had agreed to a cease-fire, which in turn poured cold water on the Soviet threats. At 0400 hours on June 9, informing neither the prime minister nor the chief of staff, both out of reach (or so he later claimed), Dayan called Elazar. The CO Northern Command was ordered to storm the Golan Heights that day. So much for command, optional or otherwise.

38

That night, however, Dayan changed his mind. As he later explained, the Egyptians had agreed to a cease-fire, which in turn poured cold water on the Soviet threats. At 0400 hours on June 9, informing neither the prime minister nor the chief of staff, both out of reach (or so he later claimed), Dayan called Elazar. The CO Northern Command was ordered to storm the Golan Heights that day. So much for command, optional or otherwise.

Once unleashed, Elazar proved as aggressive as his fellow commanders. Already on June 6 the Syrian positions had come under heavy attack at the hands of the IAF. Elazar now postponed his assault from early to late morning—thus enabling Hod’s pilots to fly another two hundred sorties and rain down four hundred tons of bombs, a tremendous amount of firepower by standards of the day; as it turned out the effort was insufficiently accurate to knock out the well-sited Syrian artillery positions.

39

Originally the Israeli plan was to take the Golan Heights from each end. Against the southern end they planned to bring up a variety of paratrooper and mechanized infantry units; these had previously been fighting against the Jordanians, however, and had to be brought up first. At this time Israeli lack of traffic discipline made itself felt, creating a jam that delayed the effort an entire day. As a result the main Israeli effort was made by the two brigades (one armored, one infantry) deployed facing the northern end of the Golan Heights. Opposite the central Golan, Elazar had a brigade of mechanized infantry and “U” Armored Brigade. The latter had already been bloodied by the Jordanians at Jenin but arrived in time to lead the effort in this sector.

39

Originally the Israeli plan was to take the Golan Heights from each end. Against the southern end they planned to bring up a variety of paratrooper and mechanized infantry units; these had previously been fighting against the Jordanians, however, and had to be brought up first. At this time Israeli lack of traffic discipline made itself felt, creating a jam that delayed the effort an entire day. As a result the main Israeli effort was made by the two brigades (one armored, one infantry) deployed facing the northern end of the Golan Heights. Opposite the central Golan, Elazar had a brigade of mechanized infantry and “U” Armored Brigade. The latter had already been bloodied by the Jordanians at Jenin but arrived in time to lead the effort in this sector.

On the face of it four brigades (discounting the force in the south) were not much to confront the Syrians. But the topography made lateral movement along the slopes impossible, so the three Syrian brigades who occupied positions on those slopes were stationary. As the IDF concentrated all its forces in two narrow wedges, only the units immediately facing them were actually hit and could fight back, whereas the remainder could not come to their support without making huge detours. The six Syrian brigades stationed on the plateau, including most of their armor, never intervened in the battle—the reason presumably being that doing so would make them easy targets for the IAF.

At 1130 hours on June 9 the advance started. The narrow approaches allowed little room for tactical, much less operational finesse; proceeding under cover of heavy air and artillery bombardment, and in some places preceded by bulldozers, teams of tanks and infantry advanced separately on the northern and central axes. The Syrian lines had been built so as to overlook each other, each successive line supported by the line behind. Now they mismanaged the battle, failing to redirect their guns; thus the farther up the slopes the IDF units climbed, the less artillery fire they received.

Ideally the attack would have been delivered by tanks and infantry working together, the former using their cannons to deliver direct fire and covering the latter’s approach. Such had been the IDF’s modus operandi as long ago as the last successful attack on Iraq Suedan in 1948. By 1967, however, that hard-learned lesson had long been forgotten. From 1956 on, the IDF was organized almost exclusively for mobile warfare, what with the armored corps looking at the infantry as an encumbrance and devising derogatory nicknames for them. Consequently the infantrymen of Golani in particular found themselves advancing very much on their own. On their way up they got involved in several hand-to-hand fights for individual positions. The positions were taken for a heavy price in blood and might have been avoided if Elazar (and Rabin) paid more attention to the peculiar conditions on this front.

Nevertheless, on the evening of June 9 the most important positions—bearing names that still strike a chord among Israelis familiar with the war, such as Tel Azaziyat and Tel Fachar—had been taken, and the IDF was standing on the escarpment. On the northern axis stood Golani Infantry Brigade and Col. Albert Mandler’s armored brigade, both of them thoroughly exhausted but about to be reinforced by another armored brigade (“B” Brigade, which had been brought back from the Jenin area). In the center the forward unit (“U” Brigade) had also been overtaken by the mechanized brigade that had been standing by in this sector and was sent up the plateau during the night. Thus Elazar had available a total of five brigades (one entirely fresh) against the remnants of the Syrian forces trying to escape from the slopes and the six uncommitted brigades that, indeed, were ordered to retreat that very night. However, at this point the IDF’s lack of previous planning made itself felt. Apparently there had been no thought given by the General Staff to the campaign’s final objectives. Nor were there any topographical features that could have forced a halt or at least a delay.

Other books

Penny Dreadful by Will Christopher Baer

Final Sacrament (Clarenceux Trilogy) by Forrester, James

Rule Breaker: A Novel of the Breeds by Leigh, Lora

LEGACY BETRAYED by Rachel Eastwood

The Burning of the World: A Memoir of 1914 by Bela Zombory-Moldovan

Signals of Distress by Jim Crace

A French Pirouette by Jennifer Bohnet

Accidental Sorceress (Hardstorm Saga Book 2) by Dana Marton

Devour by Andrea Heltsley