The Sword And The Olive (4 page)

Read The Sword And The Olive Online

Authors: Martin van Creveld

During the 1880s the “old” Jewish population began to be joined by newcomers who made their way out after the pogroms that followed the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881; twenty years later they were joined by another wave, in turn driven out by the pogroms that shook Russia’s Jewish community after the country’s defeat in the war against Japan.

10

The total number of immigrants may have been around 40,000, though it is estimated that only half of them stayed. Forming part of the great Jewish emigration movement that was leaving eastern Europe during those years, many belonged to the poorest classes. Others were members of the intelligentsia, a Russian term referring to people who were generally well educated (e.g., professionals) but not property-owning. Having alienated their families by attending non-Jewish high schools and even university, upon graduation many also found themselves rejected by their gentile environment, which refused to accept them on equal terms. As in all emigration movements aiming to settle in underdeveloped countries, males predominated. Almost all who arrived in Palestine were young and unmarried, a fact by no means insignificant in determining the kinds of lives that they took up and the ideals they entertained.

10

The total number of immigrants may have been around 40,000, though it is estimated that only half of them stayed. Forming part of the great Jewish emigration movement that was leaving eastern Europe during those years, many belonged to the poorest classes. Others were members of the intelligentsia, a Russian term referring to people who were generally well educated (e.g., professionals) but not property-owning. Having alienated their families by attending non-Jewish high schools and even university, upon graduation many also found themselves rejected by their gentile environment, which refused to accept them on equal terms. As in all emigration movements aiming to settle in underdeveloped countries, males predominated. Almost all who arrived in Palestine were young and unmarried, a fact by no means insignificant in determining the kinds of lives that they took up and the ideals they entertained.

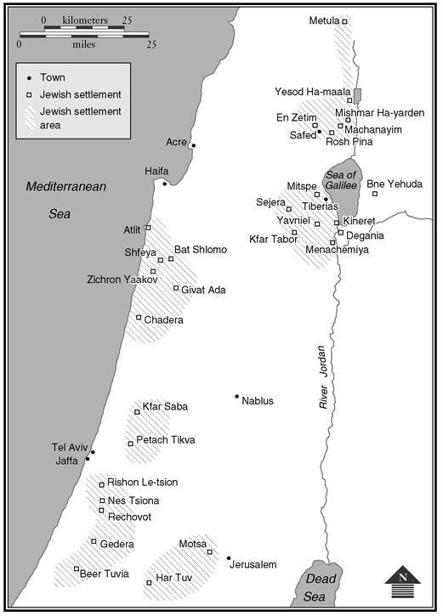

Whereas less than 20 percent of the Arab population was urban, more than 80 percent of the Jews, both old and new, lived in the towns. The most prominent was Jerusalem, half its population (50,000 total) being Jewish. Others were Safed, Tiberias, Haifa, Jaffa, and Tel Aviv (the latter a purely Jewish town that was founded in 1909 and grew very rapidly). The remaining 20 percent or so of Jews, however, went out to the countryside. The land on which they settled was mostly waste, such as the malaria-bearing swampland in the Valley of Esdraelon and around the settlement of Chadera in the center of the Sharon Plain. It had been purchased, often from absentee landlords, first by the Parisian Rothschilds, who donated large sums of money for the purpose, and later by the Jewish Colonization Association, the first bank founded by the Zionists. Settlements such as Rosh Pina (the earliest of the lot), Sejera, Yavniel, Merchavia, Tel Adashim, Rechovot, Rishon Le-tsion, Nes Tsiona, Gedera, and others came into being (see Map 1.1); most only numbered a few dozen inhabitants although the largest, Petach Tikva, already had 700 in 1897. It was in these settlements that a “security” problem first arose between Jews and Arabs (see Map 6.1).

Although joined by some recent immigrants, especially from Egypt, Lebanon, and Algeria,

11

most of the Arab population had been living in the area for centuries. Although not in possession of formal title,

12

it had often been using the land in question for hunting, grazing, wood-gathering, and the like, a problem not at all unique to Palestine but one with consequences felt equally in countries such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. In fact, the difference between the formal, individual, Western landowning system and the antiquated, informal, family- or clan-based one prevailing in much of the Ottoman empire persists in much of the West Bank and even in parts of the Negev Desert, where it sometimes gives rise to conflicts. At that time it often led to quarrels over grazing rights, water holes, rights to fruit- bearing trees, and the like, as well as plain theft and robbery.

13

The unsettled conditions created a demand for guards—who in the best Ottoman tradition themselves sometimes turned robber and blackmailed their employers. Many of them were Circessians, members of a Muslim people who had left their native Caucasus during the 1870s to avoid coming under Russian rule. Though they had since become acclimatized, they still retained their separate identity, as they do to the present day.

11

most of the Arab population had been living in the area for centuries. Although not in possession of formal title,

12

it had often been using the land in question for hunting, grazing, wood-gathering, and the like, a problem not at all unique to Palestine but one with consequences felt equally in countries such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. In fact, the difference between the formal, individual, Western landowning system and the antiquated, informal, family- or clan-based one prevailing in much of the Ottoman empire persists in much of the West Bank and even in parts of the Negev Desert, where it sometimes gives rise to conflicts. At that time it often led to quarrels over grazing rights, water holes, rights to fruit- bearing trees, and the like, as well as plain theft and robbery.

13

The unsettled conditions created a demand for guards—who in the best Ottoman tradition themselves sometimes turned robber and blackmailed their employers. Many of them were Circessians, members of a Muslim people who had left their native Caucasus during the 1870s to avoid coming under Russian rule. Though they had since become acclimatized, they still retained their separate identity, as they do to the present day.

MAP 1.1 JEWISH SETTLEMENTS IN PALESTINE, 1914

Apart from the desire to escape pogroms and poverty, the newly arrived Jewish settlers also brought with them certain ideas. Prominent among them was the need to leave the traditional Jewish occupations such as innkeeping, small-scale trading, lending, and the like, into which they had been driven by centuries of persecution as well as the prohibition on owning land. This situation had supposedly created a race of

Luftmenschen

(Yiddish for air men), that is, a race of petty hagglers whose souls were as arid, as cramped, and as devoid of wider vistas as the

shtetels

in which they spent their lives.

14

Taking up the anti-Semitic stereotypes created by the societies in which they were born, some early Zionists even went so far as to claim that Jews did not know how to dress, walk, or behave themselves.

15

In any case they dreamed of taking up agriculture, both as a way to earn an honest living without the need for intermediaries and to regenerate individually and as a community.

Luftmenschen

(Yiddish for air men), that is, a race of petty hagglers whose souls were as arid, as cramped, and as devoid of wider vistas as the

shtetels

in which they spent their lives.

14

Taking up the anti-Semitic stereotypes created by the societies in which they were born, some early Zionists even went so far as to claim that Jews did not know how to dress, walk, or behave themselves.

15

In any case they dreamed of taking up agriculture, both as a way to earn an honest living without the need for intermediaries and to regenerate individually and as a community.

Along with the declared preference for an agricultural way of life came socialist and even communist ideas. (Throughout the period between 1880 and 1917, Jews, hoping that a brave new society would do away with discrimination, were prominent in the movements that led to the Russian Revolution.)

16

Some of these ideas derived from books—first those of Saint Simon and Fourier—whose solution to the problems of this world was the establishment of self-contained agricultural communities—and later those of Marx. However, probably the most important motive behind the adoption of socialism and collective forms of settlement such as the

moshavim

and

kibbutsim

was the fact that the purchasing agencies normally made land available to groups rather than to individuals. Another was the practical problems that the immigrants faced in their new country. Young, penniless, and often acquainted with each other from back home, they clustered together in search of work and a place to live. This was carried to the point that entire families might occupy a single shanty and two people shared a pair of boots.

16

Some of these ideas derived from books—first those of Saint Simon and Fourier—whose solution to the problems of this world was the establishment of self-contained agricultural communities—and later those of Marx. However, probably the most important motive behind the adoption of socialism and collective forms of settlement such as the

moshavim

and

kibbutsim

was the fact that the purchasing agencies normally made land available to groups rather than to individuals. Another was the practical problems that the immigrants faced in their new country. Young, penniless, and often acquainted with each other from back home, they clustered together in search of work and a place to live. This was carried to the point that entire families might occupy a single shanty and two people shared a pair of boots.

Although the Old Testament has plenty to say about war and warfare, during the period of the Diaspora (starting in 70 A.D.) any idea of organized Jewish military action appeared almost entirely preposterous. Hence, and beginning already around 200 A.D., a long line of scholars had begun removing all reference to it from Jewish thought, even to the point where their exegesis turned King David from a commander into a scholar and his band of champions from soldiers into

yeshive

students.

17

During the first half of the nineteenth century, however, the wind began to change. In Thessaloniki and elsewhere, a few rabbis came under the influence of the Greek and Italian struggles for independence. They started looking forward to the day when the Jews too would set out to reconquer their ancient country, weapons in hand.

18

After midcentury such ideas were no longer rare. In 1862 the well-known Pomeranian rabbi Tsvi Kalisher followed up his Palestinian journey by publishing

Greetings from Zion

, drawing up a comprehensive and, as he claimed, divinely inspired plan for the Jewish resettlement of Palestine. In the process, “battle-worthy guards” would have to be mounted to prevent the “tent-dwelling” sons of Yishmael from “destroying the seed and uprooting the vineyards.”

19

yeshive

students.

17

During the first half of the nineteenth century, however, the wind began to change. In Thessaloniki and elsewhere, a few rabbis came under the influence of the Greek and Italian struggles for independence. They started looking forward to the day when the Jews too would set out to reconquer their ancient country, weapons in hand.

18

After midcentury such ideas were no longer rare. In 1862 the well-known Pomeranian rabbi Tsvi Kalisher followed up his Palestinian journey by publishing

Greetings from Zion

, drawing up a comprehensive and, as he claimed, divinely inspired plan for the Jewish resettlement of Palestine. In the process, “battle-worthy guards” would have to be mounted to prevent the “tent-dwelling” sons of Yishmael from “destroying the seed and uprooting the vineyards.”

19

But whereas Kalisher and his followers were strictly orthodox—much later, they were to found the MAFDAL (National Religious Party)—many of the Zionists who followed him had freed themselves from their parents’ religious beliefs and were strongly secular-minded, even atheistic. In their hands the longing for settling the country, including the establishment of some kind of Jewish army, did not link up with the

Torah

but with Jewish history, particularly during the Hellenistic and Roman periods with which many of them were familiar from their school days. Hence, for example, the sudden popularity of “Maccabee” (Maccabean) and “Bar Kochva” (after the leader of an anti-Roman Revolt in 132-135 A.D.) as names for Jewish student associations and the like—to say nothing of a Viennese sports club known simply as Ha-koach (The Force). It was in this context, too, that the story of Masada was resurrected.

20

Of all the ancient sources that describe the Jewish revolt against Roman rule in 66-73 A.D., Jewish as well as non-Jewish, the only one to mention Masada is Josephus. During the Diaspora centuries the episode was all but ignored by Jewish scholarship, which did not approve of suicide under any circumstances. In the hands of the

chalutsim

(pioneers) it was revived, however, until it became inflated into a symbol of national heroism—“again Masada will not fall.”

Torah

but with Jewish history, particularly during the Hellenistic and Roman periods with which many of them were familiar from their school days. Hence, for example, the sudden popularity of “Maccabee” (Maccabean) and “Bar Kochva” (after the leader of an anti-Roman Revolt in 132-135 A.D.) as names for Jewish student associations and the like—to say nothing of a Viennese sports club known simply as Ha-koach (The Force). It was in this context, too, that the story of Masada was resurrected.

20

Of all the ancient sources that describe the Jewish revolt against Roman rule in 66-73 A.D., Jewish as well as non-Jewish, the only one to mention Masada is Josephus. During the Diaspora centuries the episode was all but ignored by Jewish scholarship, which did not approve of suicide under any circumstances. In the hands of the

chalutsim

(pioneers) it was revived, however, until it became inflated into a symbol of national heroism—“again Masada will not fall.”

When the

Biluyim

, whose role in Zionism is akin to that of the

Mayflower

Pilgrims in the English settlement of North America, arrived in 1882, their “constitution” already included a clause concerning the need to master the use of weapons for self-defense.

21

A few years later one of their number, Yaakov Cohen, wrote a poem about the need to “deliver our country by the force of arms.” Having fallen “by blood and fire,” Judaea would likewise rise “by blood and fire.”

22

In this way he unwittingly coined a slogan that would be adopted by some of the ancestors of today’s Likud Party.

Biluyim

, whose role in Zionism is akin to that of the

Mayflower

Pilgrims in the English settlement of North America, arrived in 1882, their “constitution” already included a clause concerning the need to master the use of weapons for self-defense.

21

A few years later one of their number, Yaakov Cohen, wrote a poem about the need to “deliver our country by the force of arms.” Having fallen “by blood and fire,” Judaea would likewise rise “by blood and fire.”

22

In this way he unwittingly coined a slogan that would be adopted by some of the ancestors of today’s Likud Party.

From 1880 on, the contrast between the supposedly cowardly “Diaspora Jew” who “avoided the ranks of heroes”

23

and the courageous Israelites depicted in the biblical Books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel A, and Samuel B became a stock-in-trade of Hebrew literature. Thus, in 1905, the poet Chayim Bialik was sent by the Zionist organization of his native Odessa to report on the pogroms that had taken place in the Ukrainian town of Kishinev. The outcome was a famous poem named “Be-ir Ha-hariga” (“In the City of Slaughter”). While wasting few words on the gentile rowdies it described the Jewish victims as “hiding in shitholes.” Not only did they refuse to move a finger even when their wives were raped in front of their eyes, but later they came running to the rabbis to ask whether those same wives could still be sexually approached or not. Another poet, Shaul Tshernichovsky, wrote ballads celebrating the heroism of King Saul on the eve of his death in the Battle of Gilboa. Yet another, Yehuda L. Gordon, sang the praise of Jewish paragons from King David through the Maccabeans all the way to the rebels of 67-70 A.D., whom he depicted as fighting the lions in the Coliseum. Later the work of all three poets, but the former two in particular, formed part of the official curriculum and were studied by generations of schoolchildren. All three still have streets named after them in every major Israeli city, as does Max Nordau, the best-selling Zionist author who invented the term

yahadut shririm

(muscular Jewry) to describe the type of person he dreamed about.

23

and the courageous Israelites depicted in the biblical Books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel A, and Samuel B became a stock-in-trade of Hebrew literature. Thus, in 1905, the poet Chayim Bialik was sent by the Zionist organization of his native Odessa to report on the pogroms that had taken place in the Ukrainian town of Kishinev. The outcome was a famous poem named “Be-ir Ha-hariga” (“In the City of Slaughter”). While wasting few words on the gentile rowdies it described the Jewish victims as “hiding in shitholes.” Not only did they refuse to move a finger even when their wives were raped in front of their eyes, but later they came running to the rabbis to ask whether those same wives could still be sexually approached or not. Another poet, Shaul Tshernichovsky, wrote ballads celebrating the heroism of King Saul on the eve of his death in the Battle of Gilboa. Yet another, Yehuda L. Gordon, sang the praise of Jewish paragons from King David through the Maccabeans all the way to the rebels of 67-70 A.D., whom he depicted as fighting the lions in the Coliseum. Later the work of all three poets, but the former two in particular, formed part of the official curriculum and were studied by generations of schoolchildren. All three still have streets named after them in every major Israeli city, as does Max Nordau, the best-selling Zionist author who invented the term

yahadut shririm

(muscular Jewry) to describe the type of person he dreamed about.

The scion of an assimilated bourgeois family in Vienna and a dyed-inthe-wool liberal, Theodor Herzl, as the founder of modern Zionism, was less enthusiastic about arms, armies, and heroic deeds. In

The Jewish State

, his most important programmatic work, he did not envisage the people’s return to their country as an enterprise to be carried out by force. Instead he emphasized the role of Jewish capital and Jewish know-how; indeed when he visited Palestine in 1898 he could see for himself that they were already beginning to revive the country. Concerning the military, all he had to say was that the coming state would be neutral (presumably he had Switzerland in mind) and would only need a small army that, however, would be provided “with every requisite of modern warfare” for keeping internal and external order.

24

Still, in the privacy of his diaries even he took a different line and allowed his imagination to run wild. As a young man he had enjoyed the pseudo-martial strutting associated with student life;

25

now he noted that the new state should permit dueling so as to help restore the Jews’ long-lost sense of honor.

26

A born impresario, he discussed the military ceremonies, tattoos, and parades that would be held to uplift the masses and imbue them with the proper martial spirit

27

and speculated about the color of the breeches to be worn by the Jewish cavalry force.

The Jewish State

, his most important programmatic work, he did not envisage the people’s return to their country as an enterprise to be carried out by force. Instead he emphasized the role of Jewish capital and Jewish know-how; indeed when he visited Palestine in 1898 he could see for himself that they were already beginning to revive the country. Concerning the military, all he had to say was that the coming state would be neutral (presumably he had Switzerland in mind) and would only need a small army that, however, would be provided “with every requisite of modern warfare” for keeping internal and external order.

24

Still, in the privacy of his diaries even he took a different line and allowed his imagination to run wild. As a young man he had enjoyed the pseudo-martial strutting associated with student life;

25

now he noted that the new state should permit dueling so as to help restore the Jews’ long-lost sense of honor.

26

A born impresario, he discussed the military ceremonies, tattoos, and parades that would be held to uplift the masses and imbue them with the proper martial spirit

27

and speculated about the color of the breeches to be worn by the Jewish cavalry force.

Prior to their arrival, a few of the immigrants had been members of improvised gangs in their Russian hometowns. They did their best to put up some kind of resistance to the pogroms and also engaged in what they called “national terror”—meaning occasional assassination attempts directed at prominent anti-Semites.

28

Convinced that force could be met only with force, it was these people who, in 1907, established the two earliest self-defense organizations: Bar Giora (after a leader in the Great Revolt against the Romans in 67-73 A.D.) and Ha-shomer (The Guard), into which the former was later absorbed. Their leader was one Joshua Chankin, then aged forty-three, who had lived in the country since 1881. With his black beard and haunted look he bore a faint resemblance to Rasputin; as a land-purchasing agent working for the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) he had access to funds. His closest comrades were one Yisrael Shochet and one Yitschak Ben Tsvi. The former was a charismatic character, a strict disciplinarian, and possessed of a strongly independent mind; this last quality would cause him to be pushed aside when Jewish self-defense became institutionalized after World War I. The latter, a mild and scholarly man, proved a better survivor and lived to become Israel’s second president in 1952.

28

Convinced that force could be met only with force, it was these people who, in 1907, established the two earliest self-defense organizations: Bar Giora (after a leader in the Great Revolt against the Romans in 67-73 A.D.) and Ha-shomer (The Guard), into which the former was later absorbed. Their leader was one Joshua Chankin, then aged forty-three, who had lived in the country since 1881. With his black beard and haunted look he bore a faint resemblance to Rasputin; as a land-purchasing agent working for the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) he had access to funds. His closest comrades were one Yisrael Shochet and one Yitschak Ben Tsvi. The former was a charismatic character, a strict disciplinarian, and possessed of a strongly independent mind; this last quality would cause him to be pushed aside when Jewish self-defense became institutionalized after World War I. The latter, a mild and scholarly man, proved a better survivor and lived to become Israel’s second president in 1952.

Other books

New Forever by Yessi Smith

Out of the Black by John Rector

Home Is Where the Bark Is by Kandy Shepherd

Daughter of Asteria (The Daughter Trilogy) by C.M. Owens

Far-Flung by Peter Cameron

URBAN: Chosen By A Kingpin by Shantel Johnson

Voices at Whisper Bend by Katherine Ayres

Creature of Habit (Book 3) by Lawson, Angel

Michael’s Wife by Marlys Millhiser

The Empress Chronicles by Suzy Vitello