The Tale of Despereaux (8 page)

Read The Tale of Despereaux Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

“I don’t need the company of a rat.”

“What about the solace a sympathetic ear can provide? Do you need that?”

“Huh?”

“Would you like to confess your sins?”

“To a rat? You’re kidding, you are.”

“Come now,” said Roscuro. “Close your eyes. Pretend that I am not a rat. Pretend that I am nothing but a voice in the darkness. A voice that cares.”

The prisoner closed his eyes. “All right,” he said. “I’ll tell you. But I’m telling you because there ain’t no point in

not

telling you, no point in keeping secrets from a dirty little rat. I ain’t in such a desperate way that I need to lie to a rat.”

The man cleared his throat. “I’m here for stealing six cows, two Jerseys and four Guernseys. Cow theft, that’s my crime.” He opened his eyes and stared into the darkness. He laughed. He closed his eyes again. “But there’s something else I done, many years ago, another crime, and they don’t even know of it.”

“Go on,” said Roscuro softly. He crept closer. He allowed one paw to touch the magical red cloth.

“I traded my girl, my own daughter, for this red tablecloth and for a hen and for a handful of cigarettes.”

“Tsk,” said Roscuro. He was not alarmed to hear of such a hideous thing. His parents, after all, had not much cared for him, and certainly, if there was any profit in it, they would have sold him. And then, too, Botticelli Remorso, one lazy Sunday afternoon, had recited from memory all the confessions he had heard from prisoners. What humans were capable of came as no surprise to Roscuro.

“And then . . .,” said the man.

“And then,” encouraged Roscuro.

“And then I done the worst thing of all: I walked away from her and she was crying and calling out for me and I did not even look back. I did not. Oh, Lord, I kept walking.” The prisoner cleared his throat. He sniffed.

“Ah,” said Roscuro. “Yes. I see.” By now, he was standing so that all four of his paws were touching the red cloth.

“Do you find comfort in this cloth that you sold your child for?”

“It’s warm,” said the man.

“Was it worth your child?”

“I like the color of it.”

“Does the cloth remind you of what you have done wrong?”

“It does,” the prisoner said. He sniffed. “It does.”

“Allow me to ease your burden,” said Roscuro. He stood on his hind legs and bowed at the waist. “I will take this reminder of your sin from you,” he said. The rat took hold of the tablecloth in his strong teeth and pulled it off the shoulders of the man.

“Hey, see here. I want that back.”

But Roscuro, reader, was quick. He pulled the tablecloth through the bars of the cell,

whoosh,

like a magic trick in reverse.

“Hey!” shouted the prisoner. “Bring that back. It’s all I got.”

“Yes,” said Roscuro, “and that is exactly why I must have it.”

“You dirty rat!” shouted the prisoner.

“Yes,” said Roscuro. “That is right. That is most accurate.”

And he left the man and dragged the tablecloth back to his nest and considered it.

What a disappointment it was! Looking at it, Roscuro knew that Botticelli was wrong. What Roscuro wanted, what he needed, was not the cloth, but the light that had shone behind it.

He wanted to be filled, flooded, blinded again with light.

And for that, reader, the rat knew that he must go upstairs.

IMAGINE, IF YOU WILL, having spent the whole of your life in a dungeon. Imagine that late one spring day, you step out of the dark and into a world of bright windows and polished floors, winking copper pots, shining suits of armor, and tapestries sewn in gold.

Imagine. And while you are imagining things, imagine this, too. Imagine that at the same time the rat steps from the dungeon and into the castle, a mouse is being born upstairs, a mouse, reader, who is destined to meet the light-bedazzled rat.

But that meeting will occur much later, and for now, the rat is nothing but happy, delighted, amazed to find himself standing in so much light.

“I,” said Roscuro, spinning dizzily from one bright thing to the next, “I will never leave. No, never. I will never go back to the dungeon. Why would I? I will never torture another prisoner. It is here that I belong.”

The rat waltzed happily from room to room until he found himself at the door to the banquet hall. He looked inside and saw gathered there King Phillip, Queen Rosemary, the Princess Pea, twenty noble people, a juggler, four minstrels, and all the king’s men. This party, reader, was a sight for a rat’s eyes. Roscuro had never seen happy people. He had known only the miserable ones. Gregory the jailer and those who were consigned to his domain did not laugh or smile or clink glasses with the person sitting next to them.

Roscuro was enchanted. Everything glittered. Everything. The gold spoons on the table and the jingle bells on the juggler’s cap, the strings on the minstrels’ guitars and the crowns on the king’s and the queen’s heads.

And the little princess! How lovely she was! How much like light itself. Her gown was covered in sequins that winked and glimmered at the rat. And when she laughed, and she laughed often, everything around her seemed to glow brighter.

“Oh, really,” said Roscuro, “this is too extraordinary. This is too wonderful. I must tell Botticelli that he was wrong. Suffering is not the answer.

Light

is the answer.”

And he made his way into the banquet hall. He lifted his tail off the ground and held it at an angle and marched in time to the music the minstrels were playing on their guitars.

The rat, reader, invited himself to the party.

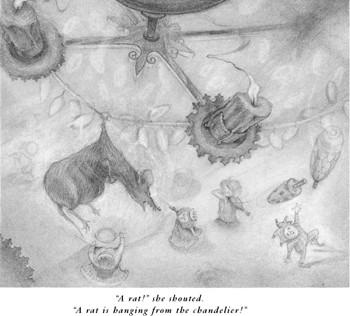

THERE WAS, in the banquet hall, a most beautiful and ornate chandelier. The crystals that hung from it caught the light of the candles on the table and the light from the face of the laughing princess. They danced to the rhythm of the minstrels’ music, swaying back and forth, twinkling and beckoning. What better place to view all this glory, all this beauty?

There was so much laughing and singing and juggling that no one noticed as Roscuro crawled up a table leg and onto the table, and from there flung himself onto the lowest branch of the chandelier.

Hanging by one paw, he swung back and forth, admiring the spectacle below him: the smells of the food, the sound of the music, and the light, the light, the light. Amazing. Unbelievable. Roscuro smiled and shook his head.

Unfortunately, a rat can hang from a chandelier for only so long before he is discovered. This would be true at even the loudest party.

Reader, do you know who it was that spotted him?

You’re right.

The sharp-eyed Princess Pea.

“A rat!” she shouted. “A rat is hanging from the chandelier!”

The party, as I have noted, was loud. The minstrels were strumming and singing. The people were laughing and eating. The man with the jingle cap was juggling and jingling.

No one, in the midst of all this merriment, heard the Pea. No one except for Roscuro.

Rat.

He had never before been aware of what an ugly word it was.

Rat.

In the middle of all that beauty, it immediately became clear that it was an extremely distasteful syllable.

Rat.

A curse, an insult, a word totally without light. And not until he heard it from the mouth of the princess did Roscuro realize that he did not like being a rat, that he did not want to be a rat. This revelation hit Roscuro with such force, that it made him lose his grip on the chandelier.

The rat, reader, fell.

And, alas, he fell right, directly, into the queen’s bowl of soup.

THE QUEEN LOVED SOUP. She loved soup more than anything in the world except for the Princess Pea and the king. And because the queen loved it, soup was served in the castle for every banquet, every lunch, and every dinner.

And what soup it was! Cook’s love and admiration for the queen and her palate moved the broth that she concocted from the level of mere food to a high art.

On this particular day, for this particular banquet, Cook had outdone herself. The soup was a masterwork, a delicate mingling of chicken, watercress, and garlic. Roscuro, as he surfaced from the bottom of the queen’s capacious bowl, could not help taking a few appreciative sips.

“Lovely,” he said, distracted for a moment from the misery of his existence, “delightful.”

“See?” shouted the Pea. “See!” She stood. She pointed her finger right at Roscuro. “It is a rat. I told you that it was a rat. He was hanging from the chandelier, and now he is in Mama’s soup!”

The musicians stopped playing their guitars. The juggler stopped juggling. The noble people stopped eating.

The queen looked at Roscuro.

Roscuro looked at the queen.

Reader, in the spirit of honesty, I must utter a difficult and unsavory truth: Rats are not beautiful creatures. They are not even cute. They are, really, rather nasty beasts, particularly if one happens to appear in your bowl of soup with pieces of watercress clinging to his whiskers.

There was a long moment of silence, and then Roscuro said to the queen, “I beg your pardon.”

In response, the queen flung her spoon in the air and made an incredible noise, a noise that was in no way worthy of a queen, a noise somewhere between the neigh of a horse and the squeal of a pig, a noise that sounded something like this:

neiggghhhhiiiinnnnkkkkkk

.

And then she said, “There is a rat in my soup.”

The queen was really a simple soul and always, her whole life, had done nothing except state the overly obvious.

She died as she lived.

“There is a rat in my soup” were the last words she uttered. She clutched her chest and fell over backward. Her royal chair hit the floor with a thump, and the banquet hall exploded. Spoons were dropped. Chairs were flung back.

“Save her!” thundered the king. “You must save her!”

All the king’s men ran to try and rescue the queen.

Roscuro climbed out of the bowl of soup. He felt that, under the circumstances, it would be best if he left. As he crawled across the tablecloth, he remembered the words of the prisoner in the dungeon, his regret that he did not look back at his daughter as he left her. And so, Roscuro turned.