The Tavernier Stones (10 page)

Read The Tavernier Stones Online

Authors: Stephen Parrish

“Impressive,” Gebhardt said. “So what does the text in the margin of the map say?”

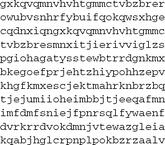

“Regrettably, it comes up gibberish.” She flipped to the front of the notebook and showed him her decipherment:

Gebhardt rose from the floor and returned to his chair. “

Now

are you finally convinced the shit is just border decoration?”

Now

are you finally convinced the shit is just border decoration?”

“Not at all. It’s likely a deeper layer of decipherment is needed.”

“Wait a minute. You said there was room for twenty-six letters. There are more than twenty-six letters in the German alphabet.”

“I would be surprised if the language turned out to be German. In fact, I’m betting one of us is going to have to employ his Latin skills.”

They stared at each other for a moment, then Gebhardt broke away and looked out the window. He wondered whether he could get his old job back.

“Don’t start panicking yet,” Blumenfeld said. “I know Latin was not your strongest subject. You have time to brush up. Meanwhile, I found it prudent to learn what other ciphers were popular in Cellarius’s day. There were several, but the most common was one called the Vigenère. Unfortunately, we need a keyword to make the Vigenère work, or even to establish whether or not it was used.”

Blumenfeld gestured for Gebhardt to view her notebook again. He rubbed his eyes, then got up and stood over the coffee table with his arms crossed. Blumenfeld was going to attack the puzzle relentlessly until she solved it. Until she could replace her Etruscan vase with a real one.

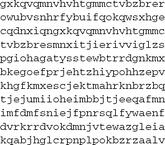

“The modern version,” she said, “a derivation of the one originally devised by Blaise de Vigenère in his 1586

Traicté des Chiffres

, employs a polyalphabetic sliding tableau.” She turned the page in her notebook and showed him the 26 x 26 table she had drawn.

Traicté des Chiffres

, employs a polyalphabetic sliding tableau.” She turned the page in her notebook and showed him the 26 x 26 table she had drawn.

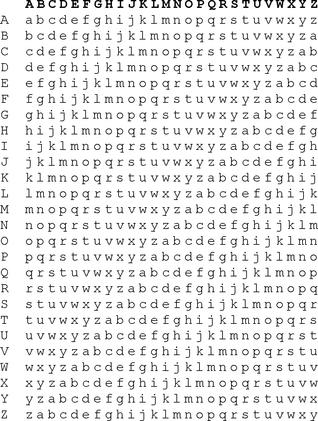

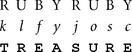

“Both sender and receiver must know the keyword. Repeating it above the cipher text in a one-to-one correspondence, the receiver finds each letter of the keyword in the vertical alphabet, then traces across into the tableau to the corresponding letter of the cipher text. Tracing up from that point, he identifies the plaintext letter in the horizontal alphabet. For example, the keyword ‘ruby’ would direct the receiver to interpret

klfyjosc

as follows:

klfyjosc

as follows:

“The Vigenère was in common use during Cellarius’s life, so it’s as good a place as any to start. Breaking the code boils down to discovering his choice of keyword.”

Gebhardt went back to his chair. “It looks like we have a hard road ahead of us on that one.”

“We? Do you have a mouse in your pocket?”

He stiffened. “Come on, Frieda. This isn’t my thing.”

“Make it your thing. Weak as your Latin may be, it’s stronger than mine. Who knows? Maybe you’ll yet vindicate your impractical ways. But don’t worry, I’ll be working on it too. The only certain connection that exists between Cellarius and Tavernier—the only real lead we have—is the ruby that was found in Cellarius’s fist. Indeed, it is this very object that leads people to suspect the runes constitute more than mere border decoration. Without it, there would be no treasure hunt. So I also need you to acquire every available photograph of large and famous rubies. The whole world knows what the bog ruby looks like. Sooner or later, somebody is going to match it up with its sisters.”

“Acquire?”

“For free. We’re on a budget.”

“I see.”

There was a knock at the door, and the maid entered the living room.

“Not now, Hannelore,” Blumenfeld said. “We’re extremely busy.”

“But a gentleman is here with a package for you. He said he had to deliver it to you personally.”

“A package?”

Gebhardt cleared his throat. “It’s, ah, you know—the things.”

“The things? Oh, the things! Well, by all means, show the gentleman in!”

Hannelore left to fetch the visitor, and Blumenfeld said to Gebhardt, “My dear Mannfred, you came through, after all.”

“Yes. And you were saying? About my impractical ways?”

A bearded old man with spectacles entered the room, carrying a cardboard tube. Blumenfeld took the tube from his hands, unrolled its stack of maps onto the floor, and peeled through them until she found the one she was looking for.

“This is it,” she said, beaming. “The Palatinate. And sure enough, Idar-Oberstein is depicted in exquisite detail.”

“Planning a visit?” the dealer asked.

“Oh, one of these days, perhaps.”

“I’ll be going there shortly myself.”

Blumenfeld and Gebhardt exchanged glances.

“To buy a piece of jewelry for my wife,” the old man explained. “Next month is our anniversary.”

Blumenfeld smiled. “Then may I suggest a ruby?”

The man shrugged. “Why not? After forty-five years of anniversary gifts, it makes little difference. She already has everything she wants.”

“Take some raw meat with you,” Gebhardt suggested.

“Excuse me?”

NINE

THE MONA LISA OF the Smithsonian gem collection was the Hope diamond, a rare blue and reputedly flawless stone weighing 45.52 carats. It held court in its own private vault built into the wall.

On Saturday morning, John shouldered his way through the rapidly assembling tourist crowd until he could peer through the bulletproof glass at the legendary diamond. The background of the display was light blue, no doubt to improve the stone’s appearance, which was dull and inky under an intense monochromatic beam of light. John thought it had the color of the sky at dawn, just before the sun appeared.

Dr. Quimby had suggested the visit. “You know about Cellarius,” he said. “Now you know about the pigpen cipher. What you don’t know anything about is the stone found in Cellarius’s fist.”

Glass models of other famous diamonds, secured in museums and private collections elsewhere, rounded out the exhibit. Among them was the 68.09-carat Taylor-Burton diamond. It struck John as funny that a glass replica of a stone Richard Burton gave to Elizabeth Taylor would draw at least as many gawkers as the genuine version of the Hope. Whoever wrote the exhibit’s placard had a wry wit: “We have seen individuals, governments, and even marriages fall victim to malevolent rocks. Apparently the only institution immune to them is the museum; none has yet suffered from owning a gemstone.”

John moved on to the next exhibit, the one he had come to the Smithsonian to see: the lost Tavernier stones. It came as no surprise that tourists and day-trippers crowded the display cases. He had to wait for the currents and eddies to favor his drift toward the front, where he steadfastly held his position to study the replicas and interpretive text at his leisure.

The most famous stone in the group was the Great Mogul diamond, which Tavernier sketched in 1665 but whose whereabouts since were unknown. It weighed about 280 carats and looked like half a hen’s egg covered with flat facets. Another missing behemoth, the Great Table diamond, was a slightly tapered, rectangular step cut with one truncated corner. Tavernier had sketched and weighed it in 1642, and had even made a model, which he sent to a prospective customer in Surat. He claimed it weighed 242 carats. No one ever laid eyes on it again.

The glass replicas sketched a chronology of old Indian styles: uncut stones, including perfect octahedra known as “glassies.” Point cuts, octahedra with polished faces. Table cuts, the result of grinding down apexes. Rose cuts. Double roses. Mogul cuts, rose cuts with high domes.

The Tears of Venus, a pair of moguls weighing 40 carats each, were thought to be among the lost Tavernier stones. According to Tavernier, the cutter was fined rather than paid because he had cut them to match rather than retained as much weight as possible.

Likewise, the Ahmadabad, a 94.5-carat stone reportedly “of perfect water.” It resembled an egg covered with facets of various polygonal shapes and was distinguished by a large natural—an unpolished area of the original surface—at its pointed end.

John stared long at one replica in particular, a rare table-cut ruby many believed to be the mother of the stone found in Cellarius’s hand. The Smithsonian had dubbed it the Tavernier ruby. It had a legend, one first related by Tavernier himself.

So deadly was the stone, it was said to have dripped blood. A shah cast it into the Krishna River as a sacrifice to the gods. But obviously the gods rejected the offer, because when the shah cut into his fish dinner the next night, the stone rolled out onto his plate.

The shah’s brother filched it. Attempting to flee the palace on his pet elephant, he was struck and fried by a bolt of lightning. The brother’s wife led a successful coup and had the shah beheaded. She was prying at his fingers to recover the stone even as his head rolled away in the dirt.

Everyone who touched the Tavernier ruby, according to the exhibit, died a writhing death—including Tavernier himself.

But the feature attraction in the exhibit was a molded replica of the ruby that had been found in Johannes Cellarius’s hand, now known simply as the Cellarius ruby.

Oval brilliant cut; 57 carats; pigeon blood red. Displayed side by side with the replica of its 285-carat table-cut mother, the exhibit slanted its presentation to make visitors believe the recut theory. Interest in the gems was so great, tourists were pressing their fingers against the glass window of the display to come as close as possible to touching the replicas.

Other books

The Gift by Danielle Steel

Indemnity: Book Two: Covenant of Trust Series by Paula Wiseman

Saving Charlie (Stories of Serendipity Book 9) by Anne Conley

Raging Star by Moira Young

Cometh the Hour: A Novel by Jeffrey Archer

Sabrina's Man by Gilbert Morris

Evocation by William Vitelli

Pimp by Slim, Iceberg

Mercenary by Duncan Falconer

The Ruby Quest by Gill Vickery