The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction (6 page)

Read The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction Online

Authors: Rachel P. Maines

Tags: #Medical, #History, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Science, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Technology & Engineering, #Electronics, #General

F

IG.

3. The patient interface for George Taylor’s steam-powered “Manipulator” of the late 1860s, from George Henry Taylor,

Pelvic and Hernial Therapeutics

(New York: J. B. Alden, 1885).

F

IG.

4. The Chattanooga Vibrator, sold to physicians for about $200 in 1900. From

The Chattanooga Vibrator

(Chattanooga, Tenn., Vibrator Instrument Company, [ca. 1904]), cover.

F

IG.

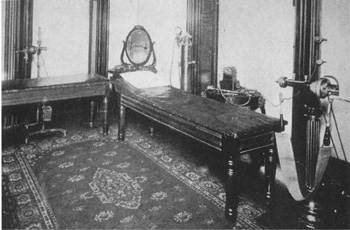

5. “Hanging type of Carpenter vibrator,” from Mary Lydia Hastings Arnold Snow,

Mechanical Vibration and Its Therapeutic Application

(New York: Scientific Authors, 1904).

Articles and textbooks on vibratory massage technique at the turn of this century praised the machine’s versatility for treating nearly all diseases in both sexes and its savings in the physician’s time and labor, especially in gynecological massage.

68

By 1905 convenient portable models were available, with impressive arrays of vibratodes, permitting use on house calls (

fig. 6

).

69

F

IG

. 6. Early twentieth-century medical vibrator at the Bakken Library and Museum of Electricity in Life.

F

IG

. 7. Operating theater, from Mary Lydia Hastings Arnold Snow,

Mechanical Vibration and Its Therapeutic Application

(New York: Scientific Authors, 1904).

In the first two decades of this century, the vibrator began to be marketed as a home appliance through advertising in such periodicals as

Needlecraft, Home Needlework Journal, Modern Women, Hearst’s, McClure’s, Woman’s Home Companion

, and

Modern Priscilla

. The device was marketed mainly to women as a health and relaxation aid, in ambiguous phrases such as “all the pleasures of youth … will throb within you.”

70

When marketed to men, vibrators were recommended as gifts for women that would benefit the male givers by restoring bright eyes and pink cheeks to their female consorts.

71

A variety of models were available at all price ranges and with various types of power, including electricity, foot pedal, and water.

72

An especially versatile vibrator line was illustrated in the Sears, Roebuck and Company

Electrical Goods

catalog for 1918. Here an advertisement headed “Aids That Every Woman Appreciates”

shows a vibrator attachment for a home motor that also drove attachments for churning, mixing, beating, grinding, buffing, and operating a fan (see

fig. 24

,

chapter 4

).

73

The social camouflage of the vibrator as a home and professional medical instrument seems to have remained more or less intact until the end of the 1920s, when the true vibrator (but not massagers or electro-therapeutic devices) gradually disappeared both from doctors’ offices and from the respectable household press. This may have been the result of greater understanding of women’s sexuality by physicians, the appearance of vibrators in stag films in the twenties, or both. Electrical trade journals of the period did not mention vibrators or report statistics on their sale as they did for other medical appliances.

74

When the vibrator reemerged during the 1960s, it was no longer a medical instrument; it had been democratized to consumers to such an extent that by the seventies it was openly marketed as a sex aid.

75

Its efficacy in producing orgasm in women became an explicit selling point in the consumer market. The women’s movement completed what had begun with the introduction of the electromechanical vibrator into the home: it put into the hands of women themselves the job nobody else wanted.

2

FEMALE SEXUALITY AS HYSTERICAL PATHOLOGY

Most of us are familiar with the current popular meanings of the word “hysterical.” Applied to a person, it means “upset to the point of irrationality”; applied to a situation, it means “very funny.” The usage has shifted from the technical designation of a disease paradigm to much more general references to uncontrolled, usually frivolous, emotions.

This development, occurring primarily since World War II, is only the latest in two and a half millennia of kaleidoscopic refocusing on feelings and behavior usually constructed as quintessentially feminine.

1

The term “hysteria” comes from a Greek word meaning simply “that which proceeds from the uterus.” “Hysterical” thus combines in its connotations the pejorative elements of femininity and of the irrational; there is no analogous word “testerical” to describe, for example, male sports fans’ behavior during the Super Bowl.

2

Hysteria as a disease paradigm has been variously constructed over time by physicians and their patients, but at all times and places it has retained its focus on the intrinsic pathology of the feminine, even (or perhaps especially) when applied to males. Assumptions of sexual pathology, of the innate “wrongness” or “otherness” of women familiar to readers of Aristotle, form the set of

basic elements—the colored glass in the kaleidoscope—that are recombined by the mechanism of social and technological change. Mainstream Western medical theory and practice have shifted these central assumptions—altering their relations, changing perspectives on them, finding new language and new conceptual frameworks in which to interpret them, but have rarely questioned the androcentric ideology that embedded these concepts in Western thought. Although physicians in the nineteenth century believed hysteria had reached epidemic proportions, the disease paradigm was by no means a Victorian invention; its antecedents were far more venerable and deeply entrenched.

In this chapter I intend to show how the disease paradigm of hysteria and its “sister” disorders in the Western medical tradition have functioned as conceptual catchalls for reconciling observed and imagined differences between an idealized androcentric sexuality and what women actually experienced. I must beg readers’ indulgence for what will of necessity be a confusing journey through the definition of hysteria; my sources contradict themselves, confuse cause and effect, or change their minds from one century or one decade to the next about the direction of causality. I have already stated that these hypotheses about the now-banished disease paradigm of hysteria had only a few common elements. Ilsa Veith’s magisterial 1965 work

Hysteria: The History of a Disease

provides a comprehensive and well-documented overview of the evolution of a disease paradigm that had, at the time of the book’s publication, only recently passed into history. Veith says that “hysteria … has adapted its symptoms to the ideas and mores current in each society; yet its predispositions and its basic features have remained more or less unchanged.” Edward Shorter, too, has written on the “blizzard of symptoms” that have at various times and places been incorporated into the concept of hysteria.

3

HYSTERIA IN ANTIQUITY AND THE MIDDLE AGES

Ancient physicians from the fifth century

B.C.

until well after the end of the classical era, whether Greek, Roman, or Egyptian, were in fairly close agreement on what hysteria was, and their definition persisted in several important strands of Western medical thought until Jean-Martin Charcot

and Sigmund Freud swept all before them at the end of the nineteenth century.

4

Freud’s view was in fact so persuasive that historians since his time have been inclined to impose his reinterpretation of the hysteroneurasthenic disorders on the preceding 2,500 years of clinical observation.

5

I shall have more to say of this at the end of this chapter.

Hysteria was a set of symptoms that varied greatly between individuals (and their physicians), including but not limited to fainting (syncope), edema or hyperemia (congestion caused by fluid retention, either localized or general), nervousness, insomnia, sensations of heaviness in the abdomen, muscle spasms, shortness of breath, loss of appetite for food or for sex with the approved male partner, and sometimes a tendency to cause trouble for others, particularly members of the patient’s immediate family.

6

The disorder was thought to be a consequence of lack of sufficient sexual intercourse, deficiency of sexual gratification, or both. Physicians committed to the androcentric model of sexuality were inclined to conflate these two etiologies and to prescribe treatment accordingly, as we shall see. Jean-Michel Oughourlian reports some of the observed characteristics of the hysterical paroxysm in clinically precise yet somehow unilluminating terms: “What is a hysterical crisis? On the clinical level, excito-motor paroxysmic accidents accompanied by convulsions and crises of inhibition with loss of consciousness, lethargy, or catalepsy have been recognized for four thousand years.”

7