The Third Reich at War (115 page)

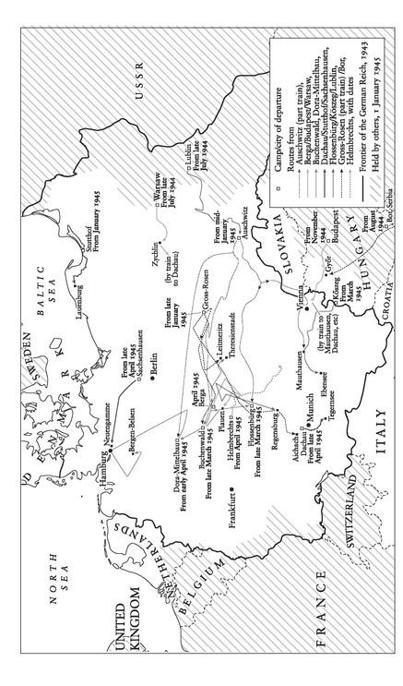

21. The Death Marches

Other evacuees from the camps were deliberately murdered en masse by the SS. A column of about a thousand prisoners evacuated from the Dora camp was penned into a barn at the town of Gardelegen for the night, and when the barn walls collapsed under the pressure of bodies, police and Hitler Youth poured petrol over the roof and burned those inside alive. Only a few were able to make their escape. The bodies were still burning when the Americans arrived the following day.

133

On some occasions, the local population in the areas through which the prisoners were marched joined in the killing. On 8 April 1945, for instance, when a column of prisoners scattered during a bombing raid on the north German town of Celle, ex-policemen and others, including some adolescents, helped hunt them down. Yet for all the particular sadism and violence directed by the SS against Jewish prisoners, the death marches were not, as has sometimes been claimed, simply the last chapter of the ‘Final Solution’; many thousands of non-Jewish camp inmates, state prisoners, forced labourers and others had to endure them, and they can best be seen as the last act in the brutal and violent history of the Third Reich’s system of repression in general, rather than an exclusive exterminatory action directed against Jews.

134

For those who survived to reach their destination, further horrors lay in store. The camps in the central area of the Reich became grossly overcrowded as a result of the arrival of the bedraggled columns of evacuees: the population of Buchenwald, for instance, went up from 37,000 in 1943 to 100,000 in January 1945. Under such conditions, death rates rose dramatically, and some 14,000 people died in the camp between January and April 1945, half of them Jews. At Mauthausen, the arrival of thousands of prisoners from sub-camps in the region led to a deterioration in conditions so drastic that 45,000 inmates died between October 1944 and May 1945. Conditions in the sub-camps that lasted to the end of the war were no better. Ohrdruf, a sub-camp of Buchenwald near Gotha, was the first to be discovered by the American army as it advanced through Thuringia. It had contained 10,000 prisoners engaged in excavating underground bunkers. The SS had marched out some of the inmates a few days before and shot many of them. The soldiers who discovered the camp on 5 April 1945 were so shocked by what they saw that their commander invited Generals Patton, Bradley and Eisenhower to visit it. ‘More than 3,200 naked, emaciated bodies,’ Bradley recalled later, ‘had been flung into shallow graves. Lice crawled over the yellowed skin of their sharp, bony frames.’ The generals came across a shed piled high with dead bodies. Bradley was so shaken that he was physically sick. Eisenhower reacted by ordering all his troops in the area to tour the camp. Similar scenes were repeated in many other places as the Americans advanced. Some of the former guards were still in the camp, disguised as prisoners; surviving inmates identified the former guards to the Allied troops, who sometimes shot the SS men in disgust; other guards had already been killed by angry prisoners wreaking their revenge.

135

The terrible conditions prevailing in the camps in the final months of the war were most evident in the place that came to symbolize the inhumanity of the SS more than any other to the British, who liberated it at the end of the war: Belsen. The concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen had been converted from a prisoner-of-war camp early in 1943. Its special function was to serve as a place of temporary accommodation for a relatively small number of Jews from various European countries, and particularly from the Netherlands, whom Himmler and his allies in the Foreign Office thought might be used as bargaining chips or hostages in international negotiations. As the difficulty of carrying out exchanges of such prisoners became more apparent, the SS decided in March 1944 to use Bergen-Belsen as a ‘convalescence camp’, or, to put it more realistically, a dumping-ground, for sick and exhausted prisoners from other camps whose weakness made them incapable of work. Up to the end of 1944, some 4,000 such prisoners had been delivered to the camp, but since they were not provided with any adequate medical facilities, the death rate quickly rose to more than 50 per cent. In August 1944 the camp was further extended to include Jewish women, many of them from Auschwitz. By December 1944 there were more than 15,000 people in the camp, including 8,000 in the women’s quarters. One of them was the young Dutch girl Anne Frank, who had been sent there at the end of October as an evacuee from Auschwitz; she died of typhus the following March. The commandant, Josef Kramer, appointed on 2 December 1944, was a long-time SS officer. He had previously served in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he had recently overseen the murder of hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews in the gas chambers. A number of officials, including women guards, accompanied him. Kramer immediately removed the few privileges enjoyed by the 6,000 or so ‘exchange Jews’ who remained from the original camp contingent, and began a regime of rapidly increasing chaos and brutality.

136

As Bergen-Belsen became the destination for prisoners evacuated from other camps in the face of the advancing Red Army, it became even more overcrowded. The number of inmates had increased to more than 44,000 by the middle of March 1945. Attempts to evacuate some of them to Theresienstadt ran into bomb attacks, and two trains were brought to a halt in open countryside on the way, when the guards absconded and Allied troops arrived to free the starving passengers, or those of them who were still alive. Meanwhile thousands more were still being delivered to Bergen-Belsen, including a large contingent from the Dora works, so that the total number of inmates reached 60,000 on 15 April 1945. Kramer had made no adequate or timely preparations for proper sanitary arrangements for them, so that these 60,000 had to make do with exactly the same number of washrooms, showers and toilets as had been provided a year earlier for a camp population of no more than 2,000. Soon excrement lay on the barrack floors up to a metre thick. Food supplies were completely inadequate; they ceased altogether as the war broke the last remaining communications. The water supply stopped when a bomb hit the pumping station, making the kitchens impossible to operate. Kramer did not bother to try to remedy the situation; yet after the British took over the camp on 15 April they were able to restore the water and food supplies and repair the cooking facilities within a few days. A doctor among the inmates later reported witnessing well over 200 cases of cannibalism among the prisoners. Kramer made things worse by constantly staging lengthy roll-calls in the open air, no matter how cold or wet the weather. Epidemics began to rage. Typhus killed thousands. But for the efforts of the doctors among the prisoners, the situation would have been even worse. Nevertheless, between the beginning of 1945 and the middle of April some 35,000 people died at Bergen-Belsen. The British, who took over the camp on 15 April 1945, were unable to rescue another 14,000, who were too weak, diseased or malnourished to recover.

137

Altogether, across Germany as a whole it has been estimated that between 200,000 and 350,000 concentration camp prisoners died on the ‘death marches’ and in the camps to which they were taken in these final months: up to half of the prisoners who were held in the camp system in January 1945, in other words, were dead four months later.

138

IV

The final phases of the war saw some of the most devastating air raids of all. Bombing continued on an almost daily basis, sometimes with such intensity that firestorms were created similar to the one that had caused such destruction in Hamburg in the summer of 1943. In Magdeburg on 16 January 1945 a firestorm killed 4,000 people and totally flattened a third of the town; it was made worse by a raid by seventy-two Mosquitos the following night, dropping mines and explosives to disrupt the work of the fire brigades and clean-up squads. Increasingly, too, bombs with time-fuses were dropped, to make things even more dangerous. Small squadrons of fast, long-range Mosquito fighter-bombers flew at will over Germany’s towns and cities, causing massive disruption by provoking repeated alarms and defensive mobilizations in the apprehension that a major raid was on the way. On 21 February 1945 more than 2,000 bombers attacked Nuremberg, flattening large areas of the city and cutting off water and electricity supplies. Two days later, on the night of 23-4 February 1945, 360 British bombers carried out the war’s only raid on the south-west German town of Pforzheim, which they bombed so intensively over a period of 22 minutes that they created a firestorm that obliterated the city centre and killed up to 17,000 out of the town’s 79,000 inhabitants. Berlin also saw its largest and most destructive raid of the war at this time. Over a thousand American bombers attacked the capital in broad daylight on 3 March 1945, pulverizing a large part of the city centre, rendering more than 100,000 people homeless, depriving the inhabitants of water and electricity, and killing nearly 3,000 people. At the request of the Soviet air force, more than 650 American bombers devastated the harbour of Swinem̈nde on 12 March, where many German refugees from the advancing Red Army had taken refuge. Some 5,000 people were killed, though popular legend soon had it that the death toll was many times higher. This was followed by an attack on Dortmund, like many of these other late raids aimed at destroying transport and communications hubs. On 16-17 March it was the turn of Ẅrzburg, where 225 British bombers destroyed more than 80 per cent of the built-up area of the town and killed around 5,000 of its inhabitants. The last substantial British night-raid of the war was launched against Potsdam on 14- 15 April 1945, killing at least 3,500.

139

The most devastating air raid of the final phase of the war was carried out on Dresden. Up to this point, the baroque city on the Elbe had been spared the horrors of aerial bombardment. However, it was not just a cultural monument but also an important communications hub and a centre of the arms industry. The Soviet advance, now nearing the Elbe, was to be aided by Allied bombing raids intended to disrupt German road and rail communications in and around the city. And the German will to resist was to be further shattered. On 13 February 1945 two waves of British bombers attacked the city centre indiscriminately, unopposed by flak batteries, which had been removed in order to man defences further east against the oncoming Red Army, or by German fighters, which remained grounded because they had no fuel. The weather was clear, and the pathfinder planes had an easy task. The British raids were followed by two daylight attacks by American bombers. The prolonged and concentrated succession of raids created a firestorm that destroyed the whole of the city centre and large parts of the suburbs. The city, wrote one inhabitant, ‘was a single sea of flames as a result of the narrow streets and closely packed buildings. The night sky glowed blood-red.’

140

35,000 people were killed.

141

Among the inhabitants of the city on those fatal days was Victor Klemperer. As one of the few remaining Jews in Germany, his life hitherto safeguarded by the loyalty of his non-Jewish wife, Eva, Klemperer had other things to worry about than the possibility of air raids. On the very morning of the first attack, an order arrived at the ‘Jews’ House’, where he was being forced to live, announcing that the remaining Jews in Dresden were to be evacuated on the 16th. The order claimed that they would be required for labour duties, but since children were also named in the accompanying list, no one had any doubts as to what it really meant. Klemperer himself had to deliver copies of the circular to those affected. He himself was not on the list, but he had no illusions about the fact that he would be on the next one. Even in the final months of the war, the Nazis were grinding the machinery of extermination ever finer.

142

That evening, while Klemperer was still contemplating his likely and imminent fate, the first wave of bombers flew over the city and began releasing their deadly cargo. At first, Klemperer hid in the cellar of the Jews’ House. Then the house was hit by a bomb-blast. He went upstairs. The windows were blown in, and there was glass everywhere. ‘Outside it was bright as day.’ Strong winds were sweeping through the streets, caused by the immense firestorm in the city centre, and there were continual bomb-blasts. ‘Then an explosion at the window close to me. Something hard and glowing hot struck the right side of my face. I put my hand up, it was covered in blood. I felt for my eye. It was still there.’ In the confusion, Klemperer became separated from his wife. Taking her jewellery and his manuscripts in a rucksack, he scrambled out of the house, past the half-destroyed cellar and into a bomb crater and on to the street, joining a group of people who were making their way up through the public gardens to a terrace overlooking the city, where they thought it would be easier to breathe. The whole city was ablaze. ‘Whenever the showers of sparks became too much for me on one side, I dodged to the other.’ It began to rain. Klemperer wrapped himself in a blanket and watched towers and buildings in the city below glowing white and then collapsing in heaps of ashes. Walking to the edge of the terrace, he came by a lucky chance upon his wife. She was still alive. She had escaped death because someone had pulled her out of the Jews’ House and taken her to a nearby cellar reserved for Aryans. Wanting to light a cigarette to relieve the stress, but lacking matches, she had seen that ‘something was glowing on the ground, she wanted to use it - it was a burning corpse’.

143

Like many others, she had made her way out of the inferno to the park.