The Third Reich at War (22 page)

By early May the rains had ceased, the Norwegian campaign was clearly drawing to a victorious close, and the moment had come. German troops invaded Holland on 10 May 1940, some being dropped by parachute, the majority simply crossing the land border from Germany itself. The Dutch army retreated, pulling away from the Anglo-French forces in the south. With only eight divisions, it was no match for the massively larger German invading army. A German bombing raid on Rotterdam on 14 May 1940, destroying the centre of the city and killing many hundreds of its civilian inhabitants, persuaded the Dutch that, to avoid further carnage, it was advisable to surrender. They did so the next day. Queen Wilhelmina and the government escaped to London to continue the struggle from across the Channel. At the same time, German paratroopers and glider-borne special forces seized key bridges and defensive emplacements and secured the main routes into Belgium, where the defending troops, failing to co-ordinate their actions with the British and French advancing to assist them, were quickly driven back. The onslaught was sudden and terrifying. William L. Shirer was amazed at the speed of the German advance. Driving into the country with a group of reporters, Shirer saw ‘railroad tracks all around torn and twisted; cars and locomotives derailed’ around the heavily bombed railway station in the town of Tongres. ‘The town itself was absolutely deserted. Two or three hungry dogs nosed sadly about the ruins, apparently searching for water, food, and their masters.’

30

Further on, they passed lines of refugees trudging along the roads, ‘old women,’ as Shirer noted, ‘lugging a baby or two in their old arms, the mothers lugging the family belongings. The lucky ones had theirs balanced on bicycles. The really lucky few on carts. Their faces - dazed, horrified, the lines frozen in sorrow and suffering, but dignified.’ Reaching Louvain, he found that the university library, burned in a deliberate act of reprisal by German soldiers in the First World War for the resistance they had encountered, later reconstructed and restocked with the help of American funds, had been destroyed again. ‘The great library building,’ Shirer noted on 20 May 1940, ‘is completely gutted. The ruins still smoulder.’ Goebbels’s propaganda machine rushed to claim it had been destroyed by the British, but the local German commander, shrugging his shoulders, told Shirer ‘there was a battle in this town . . . Heavy fighting in the streets. Artillery and bombs.’ All the books had been burned, he said.

31

The German advance continued amidst heavy fighting. With twenty-two divisions at its command, the Belgian army could put up a tougher resistance than the Dutch. But it too was overwhelmed. On 28 May 1940 the Belgian king, Leopold III, without consulting the British or the French, surrendered. Rejecting his government’s advice to follow it into exile in London, Leopold stayed on. He was kept in confinement by the Germans for the rest of the war.

32

The Belgian king’s decision to surrender was heavily influenced by events that had been occurring further south. On 10 May 1940, at the same time as German armies invaded Belgium and Holland, a large German force began advancing secretly through the Ardennes. The French felt confident of their ability to withstand a German invasion. Rearmament had been proceeding apace, and by early 1940 the French had around 3,000 modern and effective tanks with which to confront a German armoured force of about 2,500 tanks of generally inferior quality, and around 11,000 artillery pieces to the Germans’ 7,400. Altogether, 93 French and 10 British divisions faced a total of 93 German divisions. The French had 647 fighters, 242 bombers and 489 reconnaissance planes at their disposal in France in the spring of 1940, and the British 261 fighters, 135 bombers and 60 reconnaissance planes, making a total of nearly 2,000 combat aircraft altogether; the German air force had around 3,578 combat planes operational at this time, but when the Belgian and Dutch air forces were thrown into the balance this was not enough in itself to overwhelm its opponents. However, despite the recent delivery of 500 modern American aircraft, many of the French planes were obsolete, and neither the British nor the French had learned how to use their planes as tactical support for ground forces in the way that the Germans had in Poland. The result was that in Holland, Belgium and France, German dive-bombers were able to destroy enemy anti-aircraft defences, batter enemy communications and establish air superiority before Allied air forces could react. Moreover, the Allies kept many of their planes in reserve, while the German air force threw almost its entire operational strength into the fray. This was a bold gamble, in which the Germans lost no fewer than 347 planes, including most of the paratroop carriers and gliders used in Holland and Belgium; but it was a gamble that paid off spectacularly.

33

French intelligence altogether failed to predict how the German invasion would take place. Some preparations were noticed, but nobody put all the information together into a coherent picture, and the generals still assumed that the now obsolete captured plans were the operative ones. Drawing on their experience of the First World War, the French military failed to grasp just how fast and how far the German armoured divisions could move. Since the stalemate of trench warfare in 1914-18, the arrival of air power and tanks had shifted the advantage in warfare from defence to attack, a development which few on the Allied side had followed to its logical conclusion. Locating themselves many miles behind the front line so as to get a better overview, the French generals suffered from poor communications and were slow to react to the fast-moving pace of events. 57 divisions were soon concentrated in the north to fight back the German invasion expected to come via Holland and Belgium. But the German forces here numbered only 29 divisions, and while the French deployed another 36 divisions along the Maginot Line, the Germans only confronted them here with 19 divisions. The strongest German force, 45 divisions, including many of their best-trained and best-equipped forces, was focused on the push through the Ardennes. Not surprisingly, initially at least the French defence in the north held firm, pushing back the Germans in the first tank battle in history, at Hannur. The real issue, however, was being decided further south, where General Ewald von Kleist was leading 134,000 soldiers, 1,222 tanks, 545 half-track armoured vehicles, and nearly 40,000 lorries and cars through the narrow wooded valleys of the Ardennes in what has been called ‘the greatest traffic jam known to that date in Europe’.

34

The enterprise was extremely risky. It left virtually no German armour in reserve. Failure would have opened up Germany to devastating counter-attacks. As Fedor von Bock, the able if conservative general commanding Army Group B to the north, had noted on first learning of the planned invasion through the Ardennes, it was clear that ‘it must run into the ground unless the French take leave of their senses’.

35

But the Germans’ luck held. Slowly and painfully, four slow-moving columns, each nearly 400 kilometres long, crawled along narrow roads towards the river Meuse (Maas). They frequently ground to a halt. Traffic managers flew up and down the columns in light aircraft to identify spots where gridlock threatened. The tanks were dependent on fuel stations set up by the advance units at previously designated spots en route. All the crews and drivers had to keep going for three days and nights without a break; crack combat units were dosed up with amphetamines (dubbed ‘panzer chocolate’ by the troops) to keep them awake. Vulnerable and exposed, the columns were sitting ducks for Allied air attacks. Yet they got away with it because the Allies failed to recognize them for the main German force. Reaching the river Meuse on 13 May 1940, the German forces came under fire from the first real French attempt to stop them. Kleist called up no fewer than 1,000 planes to bombard the French positions, which they did in waves of attacks lasting some eight hours, forcing the French to take cover or withdraw and severely denting their morale. Hundreds of rubber dinghies were now thrown into the river by the Germans, and German troops landed on the other side in three places, destroying French defensive positions and creating a foothold on the left bank large enough for engineers to build a bridge over which the German tanks could start to cross.

36

This was the crucial breakthrough. True, at this point the German forces were still vulnerable to counter-attack, but the French were again too slow to react, and they were once more surprised when, instead of turning east to assault the Maginot Line from behind, as they expected, Kleist’s men turned west, in Manstein’s famous ‘sickle-cut’, designed to pin the Allied forces in Belgium up against the invading German army in the north and jointly drive them into the sea. By the time they got to the Meuse, the French tanks were heavily outnumbered by their German counterparts. Many of them ran out of petrol. Most were destroyed. Allied aircraft were far away, in central and northern Belgium, and when they finally arrived, they found the ground targets difficult to pinpoint. They were also heavily damaged by German anti-aircraft fire: the British lost 30 bombers out of a force of 71. Meanwhile German tanks powered their way rapidly westward across the open plain. In many cases, the German commanders, carried away by the momentum of the attack, advanced farther and faster than their more cautious superiors had intended. French troops marching to the front were amazed to find the Germans so far west. The French army leadership was in despair. At staff headquarters, generals burst into tears when they learned of the speed and success of the German advance. On the morning of 15 May 1940 the French Prime Minister, Paul Reynaud, telephoned Churchill. ‘We have been defeated,’ he said. The French had deprived themselves of reserves to throw into the battle by over-committing themselves in Belgium. On 16 May 1940 Churchill arrived in Paris for a hurried conference with the French leaders. ‘Utter dejection was written on every face,’ he later reported. The French Commander-in-Chief, General Maurice Gamelin, reported despairingly that he could not stage a counter-attack: ‘inferiority of numbers, inferiority of equipment, inferiority of method,’ he said, accompanying his words, as Churchill later noted, with ‘a hopeless shrug of the shoulders’.

37

On 19 May 1940 Reynaud dismissed Gamelin, whose reputation for caution had proved so fatally well merited, and replaced him with General Maxime Weygand, a much-admired veteran of the First World War who had retired in 1935. It was too late. The next day, the first German tanks reached the Channel. The Allied armies in Belgium were now surrounded by German divisions on three sides, with the sea on the fourth. Weygand decided that the German panzer advance could be broken by a simultaneous attack from north and south, but it soon became clear that the situation had become so chaotic that a co-ordinated offensive was impossible. Meeting with the Belgian king, Weygand concluded correctly that Leopold had already given up the struggle. Communications between the British and French effectively broke down. All attempts to locate the British Commander-in-Chief, Lord Gort, failed.

38

The French general in overall command of the northern forces was killed in a car crash, and no satisfactory replacement could be found. The planned counter-attack foundered amidst a welter of mutual recriminations. The British began to feel that the French were incompetent, the French that the British were unreliable. Things only got worse with the Belgian capitulation on 28 May. On hearing the news, Reynaud was said to be ‘white with rage’, while Britain’s prime minister in the First World War, David Lloyd George, wrote that it would be hard ‘to find a blacker and more squalid sample of perfidy and poltroonery than that perpetrated by the King of the Belgians’. As the three-pronged German panzer attack swept up north and west to meet the other German forces advancing through Belgium from the east, the British and French began to fall back on the port of Dunkirk.

39

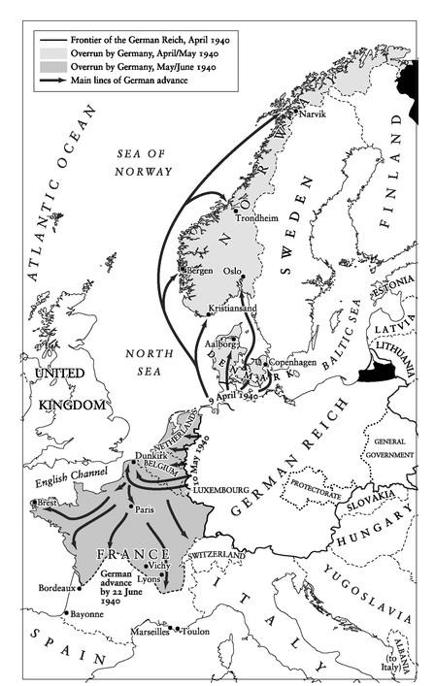

6. The German Conquest of Western Europe, 1940

On the day of Gamelin’s dismissal, the British government, anticipating these events, began to assemble a fleet, consisting of almost any boats and ships that could be found along the English coast and could get to the area in time, to carry out the evacuation. Strafed and pounded by German dive-bombers, 860 vessels, some 700 of them British, made their way to the Dunkirk beaches and took off nearly 340,000 soldiers to England. Nearly 200,000 of them were British, the rest mostly French. Far fewer would have escaped had Hitler not personally ordered the German advance to halt, reassured by Göring’s boast that his planes would finish off the Allied troops, and advised by Rundstedt to give his tired troops a respite before they turned southwards towards Paris. Neither Brauchitsch, the army chief, nor Fedor von Bock, the commander of Army Group B, on the northern front, could understand it. Bock told Brauchitsch that the attack had to be urgently resumed, ‘otherwise it could happen to us that the English can transport whatever they want, under our very noses, from Dunkirk’. But Hitler backed Rundstedt, seeing in this a chance of asserting his authority over the top commanders. By the time Brauchitsch had persuaded Hitler to resume the attack, the evacuation was under way, and the fierce resistance of the defending troops was too much for the weary Germans. ‘At Dunkirk, ’ noted Bock with evident irritation on 30 May 1940,