The Third Reich at War (20 page)

The effect on public opinion, the SS Security Service reported sycophantically, was to provoke a popular reaction against the British. ‘Love of the Leader has grown even more, and attitudes to the war have become even more positive in many parts of the population as a result of the assassination attempt.’

4

So widespread was this effect that the American reporter William L. Shirer thought the Nazis themselves had staged the attack in order to win sympathy. Why otherwise, he mused, had the ‘bigwigs . . . fairly scampered out of the building’ instead of staying to chat?

5

But this theory, though also believed by some later historians, was as little based in fact as was the Nazis’ own counter-theory of British inspiration for the attempt.

6

Elser himself was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. A formal trial would have brought into the public domain the fact that he had acted alone, and Hitler and the leading Nazis preferred to maintain the fiction that he had been part of a plot hatched by the British Secret Service. Elser refused steadfastly to tell anything but the truth. Just in case he changed his mind, he was kept in the camp as a special prisoner, and given two rooms for his sole use. He was even allowed to use one of them as a workshop so that he could continue practising his craft as a cabinet-maker. He received a regular supply of cigarettes and whiled away the time by playing the zither. He was not allowed to speak to other prisoners or receive visitors. But his death would not have served any purpose without the kind of confession the Nazis wanted, and this was never forthcoming.

7

II

The assassination attempt came at a moment when Hitler was turning his attention to the conflict with Britain and France, after the stunning success of his conquest of Poland. Both countries had declared war on Germany immediately after the invasion. But from the very beginning, they realized that there was little they could do to help the Poles. They were already well armed in the mid-1930s, but had only begun to increase the pace of arms manufacture in 1936 and needed more time. In the beginning, they thought, the war would be a defensive one on their part; only later, when they were a match for the Germans in men and equipment, could they go onto the attack. This was the period of the ‘phoney war’, the

drˆle de guerre

, the

Sitzkrieg

, while every combatant nation waited nervously for the start of major action. On 9 October 1939, Hitler told the German armed forces that he would launch an attack in the west if the British refused to compromise. The leadership of the German army warned, however, that the Polish campaign had used up too many resources and it needed time to recover. Moreover, the French and the British would surely be far more formidable opponents than the Poles.

8

Hitler was dismayed by such caution, and on 23 November 1939 he reminded a meeting of 200 senior officers that the generals had been nervous about the remilitarization of the Rhineland, the annexation of Austria, the invasion of Czechoslovakia and other bold policies that had turned out to be triumphs in the end. The ultimate goal of the war, he told them, not for the first time, was the creation of ‘living-space’ in the east. If this was not conquered, then the German people would die out. ‘We can oppose Russia only when we are free in the west,’ he warned. Russia would be militarily weak for the next two years at least, so now was the time to secure Germany’s rear and avoid the two-front war that had been so crippling in 1914- 18. England could only be defeated after the conquest of France, Belgium and Holland and the occupation of the Channel coast. This would have to take place as soon as possible, therefore. Germany was stronger than ever before. More than a hundred divisions were ready to go into the attack. The supply situation was good. Britain and France had not completed their rearmament. Above all, said Hitler, Germany had one factor that made it unbeatable - himself. ‘I am convinced of the powers of my intellect and of decision . . . The fate of the Reich depends on me alone . . . I shall shrink from nothing and shall destroy everyone who is opposed to me.’ Destiny was with him, he proclaimed, buoyed up by his escape from the beer-cellar bomb a fortnight before. ‘Even in the present development I see Providence.’

9

The leading generals were appalled by this fresh outburst of what they considered Hitler’s irresponsible aggressiveness. Time was needed, they pleaded, to train more recruits, and to repair and replenish the equipment damaged or lost in the Polish campaign. The Chief of the Army General Staff, Franz von Halder, was so alarmed that he took up again the conspiratorial plans he had been hatching with fellow officers, discontented spirits in army counter-intelligence and conservative civil servants and politicians, during a similar confrontation over the proposed invasion of Czechoslovakia in the summer of 1938. For a time he even went around with a loaded revolver concealed on his person, in the hope of shooting Hitler when the occasion presented itself. Only Halder’s ingrained sense of obedience to his oath of loyalty to the Nazi Leader, and the knowledge that he would have little support from the public or indeed his junior officers, prevented him from using it. During November 1939 the conspirators began again to prepare to arrest Hitler and his principal aides, with the idea of putting G̈ring in power, since he was known to have serious doubts about a war with Britain and France. On 23 November 1939, however, Hitler addressed his senior generals. ‘The Leader,’ noted one of them, ‘takes a stand in the strongest manner against defeatism of any kind.’ His speech betrayed ‘a certain mood of ill-humour towards the leaders of the army’. ‘ “Victory,” he said, “cannot be won by waiting!” ’

10

Halder panicked, believing Hitler had got wind of the plot, and pulled out of it altogether. It fell apart. Ultimately, the lack of communication and co-ordination between the plotters, and the absence of any concrete plans for the period after Hitler’s arrest, had doomed the conspiracy to failure from the outset.

11

In the end, in any case, the confrontation proved unnecessary, for Hitler was forced to postpone the offensive time and again through the winter of 1939- 40 because of poor weather conditions. Constant heavy rain turned the ground to mud across large tracts of Western Europe, making it impossible for German tanks and heavy armour to move with the rapidity that had played such a key part in the Polish campaign. The months of delay proved beneficial to German war preparations as Hitler brought about major changes in the armaments programme. In the later 1930s he had been demanding the building of an air force on an enormous scale. But Germany lacked sufficient supplies of aircraft fuel. And by the summer of 1939 shortages of steel and other raw materials, as well as of qualified construction engineers, were leading to a drastic scaling-back of the construction programme. Aircraft production also had to compete for priority with tanks and battleships. In August 1939 Hitler was persuaded by intensive lobbying on behalf of the Air Ministry to put the production of Junkers 88 bombers back on the top of the agenda. A cutback in the naval building programme also allowed Hitler to demand a massive increase in the manufacture of ammunition, especially artillery shells. From this point on, airplanes and ammunition always took up two-thirds or more of arms production resources. But these changes were slow to work their way through the planning and production systems, as fresh blueprints had to be drawn, machines retooled, equipment built, existing factories redeployed and new ones opened. Labour shortages were compounded by the call-up of workers to the armed forces, while under-investment in the German railway system meant that there was not enough rolling-stock to carry armaments, components and raw materials around the country, and coal supplies for industry began to be seriously held up. All these factors took time to overcome.

12

It was not until February 1940 that ammunition output began to increase significantly. By July 1940 German production of armaments had doubled.

13

By this time, however, Hitler had already lost patience with the armaments procurement system run by the armed forces under the leadership of Major-General Georg Thomas. On 17 March 1940 he set up a new Reich Ministry for Munitions. The man he put in charge of it was Fritz Todt, his favourite engineer, who had masterminded one of Hitler’s pet projects in the 1930s, the construction of the new motorway system.

14

So dismayed was the head of the army’s procurement office, General Karl Becker, at this development, and the accompanying whispering campaign against the alleged inefficiency of his organization, orchestrated in part by representatives of arms companies like Krupps, who saw an opportunity in the new arrangement, that he shot himself. Todt immediately set up a system of committees for different aspects of arms production, with industrialists playing the leading role. The surge in arms production that took place over the following months was largely the achievement of the previous procurement regime in unblocking supply bottlenecks of vital raw materials such as copper and steel. But the credit went entirely to Todt.

15

III

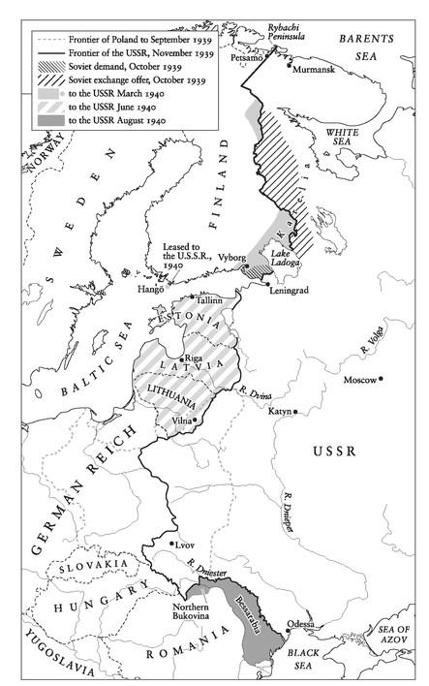

The Nazi- Soviet Pact and further negotiations surrounding the invasion of Poland had resulted in a German assignment to the Russian sphere of influence not only of Eastern Poland and the Baltic states but also of Finland. In October 1939, Stalin demanded that the Finns cede to Russia the area immediately north of Leningrad, and the western part of the Rybachi peninsula, in return for a large area of eastern Karelia. But negotiations broke down on 9 November 1939. On 30 November the Red Army invaded, installed a puppet Communist government in a Finnish border town, and got it to sign an agreement ceding the territory that Stalin had been demanding. At this point, however, things began to go seriously wrong for the Soviet leader. Many of the senior Soviet generals had been eliminated in the purges of the 1930s, and the Soviet troops were unprepared and poorly led. Winter had already set in, and white-clad Finnish troops, moving swiftly about on skis, outmanoeuvred raw Soviet conscripts who had not been trained for fighting in deep snow. Indeed, some Soviet officers regarded such camouflage as a badge of cowardice and refused to employ it even when it was available. Trained only to attack, whole Red Army units went to their deaths as they ran straight at machine-gun nests built into the defensive bunkers of the Mannerheim Line, a lengthy series of concrete trenches named after the Finnish Commander-in-Chief.

16

‘They are swatting us like flies,’ a Soviet infantryman on the Finnish front complained in December 1939. By the time the conflict was over, more than 126,000 Soviet troops had been killed and another 300,000 evacuated from the front because of injury, disease or frostbite. Finnish losses were also severe, indeed proportionately even more so, at 50,000 killed and 43,000 wounded. Nevertheless, there was no doubt that the Finns had given the Soviets a bloody nose. Their troops showed not only courage and determination, fuelled by strong nationalist commitment, but also ingenuity. Borrowing from the example of Franco’s forces in the Spanish Civil War, the Finns took empty bottles of spirits, filled them with kerosene and other chemicals, stuck a wick in each of them, then lit them and threw them at incoming Soviet tanks, covering them with flames. ‘I never knew a tank could burn for quite that long,’ said a Finnish veteran. They devised a new name for the projectile, too: in honour of the Soviet Foreign Minister they called them ‘Molotov cocktails’.

17

In the end, however, numbers told. After a second offensive thrust had failed, Stalin called in huge reinforcements, at the same time dropping his puppet Finnish government and offering negotiations to the legitimate Finnish regime in Helsinki. On the night of 12- 13 March 1940, recognizing the inevitable, the Finns agreed a peace deal which allotted to the Soviet Union a substantially larger amount of territory in the south than it had originally demanded. Despite their eventual defeat, however, and the opening of a Soviet military base on their territory, the Finns had retained their independence. Their tough and effective resistance had exposed the weakness of the Red Army and convinced Hitler that he had nothing to fear from it. For Stalin, Finland would now serve as a subservient buffer-state to insulate Russia against any conflict between Germany and the Allies that might be fought out in Scandinavia. The many setbacks and disasters of the war persuaded Stalin to recall purged and disgraced former officers to active service in senior positions. They also prodded his generals into embarking on sweeping military reforms that they hoped would ensure that the Red Army would put on a better performance the next time it went into action.

18