The Third Reich at War (8 page)

They did not reopen. Soon after, the German administration began to attack standards of education in the local elementary schools. Dr Klukowski noted on 25 January 1940: ‘Today the Germans ordered all school principals to take from the students handbooks of the Polish language as well as history and geography texts. In every Szczebrzeszyn school, in every classroom, children returned books . . . I am in shock and deeply depressed.’

108

Worse was to come, for on 17 April 1941, he reported, ‘the Germans removed from the attic of the grammar school buildings all books and teaching supplies. They were piled up on the playground and burned.’ Polish intellectuals and teachers did their best to organize advanced lessons informally and in secret, but given the mass murder of so many of them by the German occupiers, such efforts met with only limited success, even if their symbolic importance was considerable.

109

Day after day, Zygmunt Klukowski recorded in his diary the murder of Polish writers, scientists, artists, musicians and intellectuals, many of them his friends. ‘Many have been killed,’ he noted on 25 November 1940, ‘many are still dying in German camps.’

110

II

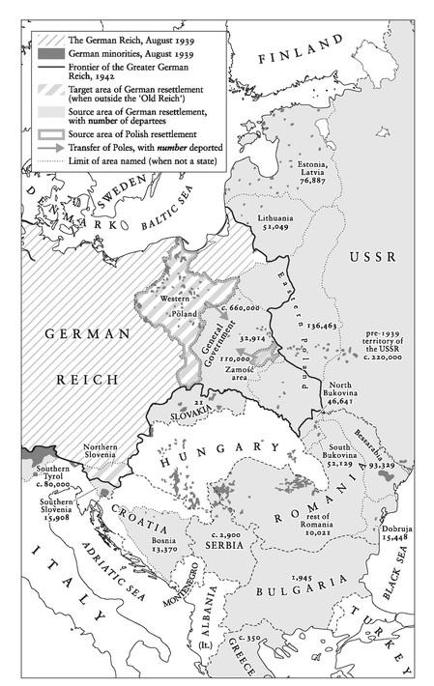

Not only were supposedly suitable Poles reclassified as German, but large numbers of ethnic Germans quickly began to be moved in to take over the farms and businesses from which the Poles had been so brutally expelled. Already in late September 1939, Hitler specifically requested the ‘repatriation’ of ethnic Germans in Latvia and Estonia as well as from the Soviet-controlled eastern part of Poland. Over the following months, Himmler took steps to carry out his wishes. Several thousand ethnic Germans were moved into the incorporated areas from the General Government, but most were transported there from areas controlled by the Soviet Union, under a series of international agreements negotiated by Himmler. So many German settlers arrived in the General Government and the incorporated territories in the course of the early 1940s that another 400,000 Poles were thrown out of their homes from March 1941 onwards, without actually being deported, so that the settlers could be provided with accommodation. Over the course of the following months and years, 136,000 ethnic Germans came in from eastern Poland, 150,000 from the Baltic states, 30,000 from the General Government and 200,000 from Romania. They were persuaded to leave by the promise of better conditions and a more prosperous life, and the threat of oppression under Soviet Communism or Romanian nationalism. By May 1943 some 408,000 had been resettled in the Wartheland and the other incorporated parts of Poland, and another 74,000 in the Old Reich.

111

In order to qualify for resettlement, all but a lucky 50,000 of the half-million immigrants were put into transit camps, of which there were more than 1,500 at the height of the transfer, and subjected to racial and political screening, a process personally approved by Hitler on 28 May 1940. Conditions in the camps, which were often converted factories, monasteries or public buildings seized from the Poles, were less than ideal, though an effort was made to keep families together, and compensation was paid in bonds or property for the assets they had been forced to leave behind. Assessors from the SS Race and Settlement Head Office based at the police immigration centre in L’d’ descended on the camps and began their work. With only four weeks’ training in the basics of racial-biological assessment, these officials were equipped with a set of guidelines, including twenty-one physical criteria (fifteen of them physiognomical) that could never be anything other than extremely rough. The immigrants were x-rayed, medically examined, photographed and questioned about their political views, their family, their job and their interests. The resulting classification ranged from ‘very suitable’ at the top end, where the immigrants were ‘purely Nordic, purely phalian or Nordic-phalian’, without any noticeable ‘defects of intellect, character or of a hereditary nature’, to ‘ethnically or biologically unsuitable’ at the bottom end, where they were considered to be of non-European blood, or to possess a malformed physique, or to be from ‘families who are socially weak or incompetent’.

112

This inevitably meant that the programme of resettlement proceeded only very slowly. Altogether, by December 1942, settlers had taken over 20 per cent of the businesses in the annexed territories, Reich Germans 8 per cent, local Germans 51 per cent, and trustees acting on behalf of the military veterans of the future another 21 per cent. Out of 928,000 farms in these districts, 47,000 had been taken over by settlers; 1.9 million out of a total of 9.2 million hectares of land had been seized from Poles and given to Germans. Yet out of the 1.25 million settlers, only 500,000 had actually been resettled by this point; the vast majority were in camps of one kind or another, and thousands of them had been there for well over a year. 3 million people had registered as Germans in the incorporated territories, but there were still 10 million Polish inhabitants of the Greater German Reich. Clearly, the Germanization programme was far from complete as it entered its fourth year.

113

The programme continued throughout 1943, as more Polish villages were compulsorily evacuated. Himmler started to use the scheme as a way of dealing with supposedly untrustworthy groups in the borderlands of the Old Reich such as Luxembourg. Families where the husband had deserted from the German army were rounded up in Lorraine and shipped off to Poland as settlers. In 1941 54,000 Slovenes were taken from the border regions of Austria to camps in Poland, where 38,000 of them were found racially valuable and treated as settlers.

114

Travelling through the evacuated villages of Wieloncza and Zawada in May 1943, Zygmunt Klukowski noted that ‘German settlers are moving in. Everywhere you can see young German boys in Hitler Youth uniforms.’

115

He continued to list villages in his area that were forcibly evacuated, their Polish inhabitants taken off to a nearby camp, well into July 1943. Visiting the camp in August 1943, Klukowski noted the inmates, behind barbed wire, were malnourished and sick, ‘barely moving, looking terrible’. In the camp hospital there were forty children under the age of five, suffering from dysentery and measles, lying two to a bed, looking ‘like skeletons’. His offer to take some of them to his own hospital was brusquely rejected by the German officials. In his own town of Szczebrzeszyn, too, Poles were increasingly being turfed out of their homes to make way for incoming German settlers.

116

The Germanization of the Zamość area, pushed through by Himmler in the teeth of opposition from Frank, was in fact intended to be the first part of a comprehensive programme affecting all of the General Government in due course, though it never got that far. Even so, some 110,000 Poles were forcibly expropriated and expelled from the Lublin region in the process, making up 31 per cent of the population, and between November 1942 and March 1943, forty-seven villages in the Zamość rea were cleared to make way for incoming Germans. Many of the Polish inhabitants fled to the forests, taking as much as they could with them, to join the underground resistance.

117

By mid-July 1943 Klukowski’s home town of Szczebrzeszyn had been officially declared a German settlement and demoted to the status of a village.

118

‘On the city streets,’ noted Klukowski, who refused to accept this insult to his home town, ‘you can see many Germans in civilian clothing, mostly women and children, all new settlers.’ New facilities were opened for them, including a kindergarten. Soon he was noting that ‘stores are run by Germans; we have German barbers, tailors, shoemakers, bakers, butchers, and mechanics. A new restaurant was opened with the name

Neue Heimat

(

New Home

).’ Those Poles who had not signed themselves on to the register of ethnic Germans were second-class citizens, used for forced labour, and treated as if their lives meant nothing. On 27 August 1943 Klukowski reported the case of an eight-year-old Polish boy who was found ‘lying in an orchard with gunshot wounds. He was taken to the hospital where he died. We learned the boy went there for apples. The new owner, a German locksmith, shot him and left him to die, without telling anyone.’

119

2. Population Transfers of Ethnic Germans, 1939-43

The Germans who moved into the Wartheland had few reservations about the expulsion of the region’s Poles to make way for them. ‘I really like the town of Posen,’ wrote Hermann Voss, an anatomist appointed to a chair in the Medical Faculty of the new Reich University of Posen, a foundation put at the apex of the German educational system in the occupied territories, in April 1941, ‘if only there were no Poles at all, it would be really lovely here.’ In May 1941 he noted in his diary that the crematorium in his university department had been taken over by the SS. He had no objections, however - rather the contrary: ‘There is a crematorium for burning corpses in the cellar of the Institute building here. It’s for the exclusive use of the Gestapo. The Poles they shoot are brought here at night and cremated. If one could only turn the whole of Polish society into ashes!’

120

In addition to the immigrants from the east, some 200,000 Germans moved into the incorporated territories from the Old Reich. A number of these were children and adolescents evacuated from Germany’s cities to avoid the dangers of aerial bombardment: thousands were put into military-style camps, where they were subjected to harsh discipline, bullying and a rough, decidedly non-academic style of education.

121

But many adults went voluntarily to the incorporated territories, seeing them as an ideal area for colonial settlement. Often they regarded themselves as pioneers. One such was Melita Maschmann, sent as press officer for the Hitler Youth in the Wartheland in November 1939. Noticing the absence of educated people amongst the Polish population, she concluded that the Poles were a miserable, poverty-stricken, underdeveloped people who were incapable of forming a viable state of their own. Their high birth-rate made them a serious threat to the German future, as she had learned from her ‘racial science’ lessons at school. She sympathized with the poverty and wretchedness of many Polish children whom she saw begging on the streets or stealing coal from the depots, but, under the influence of Nazi propaganda, she later wrote:

I told myself that if the Poles were using every means in the fight not to lose that disputed eastern province which the German nation required as ‘

Lebensraum

’, then they remained our enemies, and I regarded it as my duty to suppress my private feelings if they conflicted with political necessity . . . A group which believes itself to be called and chosen to lead, as we did, has no inhibitions when it comes to taking territory from ‘inferior elements’.

Though she distanced herself from those Germans who had no doubt that Germans were a ‘master race’ and Poles destined to be slaves, still, she wrote later: ‘My colleagues and I felt it was an honour to be allowed to help in “conquering” this area for our own nation and for German culture. We had the arrogant enthusiasm of the “cultural missionary”.’

Maschmann and her colleagues were charged with clearing out and cleaning up Polish farms in readiness for their new German inhabitants, and took part in the SS-led expulsions without asking where the expelled Poles were going.

122

She unashamedly joined in the extensive looting of Polish property during this process, as the departing Poles were obliged to leave furniture and equipment behind for the German settlers. Armed with a forged requisition order and a pistol (which she did not know how to use), she even robbed beds, cutlery and other items from Polish farmers in areas where resettlement had not begun, to give them to incoming ethnic Germans. All this she considered completely justified; the whole experience of her work was entirely positive.

123

These feelings were shared by many other German women who came into the incorporated territories as volunteers or were posted there as newly qualified teachers, junior officials in Nazi women’s organizations, or aspiring civil servants. All of them, both at the time and in many cases when interviewed about their work decades later, saw their activities in occupied Poland as part of a civilizing mission and recorded their horror at the poverty and dirt they encountered in the Polish population. At the same time they enjoyed the beauty of the countryside and the sense of being on an exciting mission far from home. As middle-class women they evidently gained fulfilment from cleaning up farms left behind by deported Poles, decorating them, and creating a sense of homeliness to welcome the settlers. For virtually all of them, the suffering of Poles and Jews was either invisible or acceptable or even justified.

124