The Third Reich at War (11 page)

In many parts of Poland apart from Warsaw, army units seized Jews as hostages, and in many places there were shootings of Jews as individuals or in groups. The 50,000 Polish prisoners of war whom the army classified as Jewish were drafted like other prisoners on to labour schemes but starved and maltreated to such an extent that 25,000 of them were dead by the spring of 1940.

169

Chaim Kaplan noted on 10 October 1939 that Jewish men were being arrested and taken away to labour schemes.

170

Frank had indeed already ordered the introduction of compulsory labour for the Jews within the General Government and begun to set up labour camps, where Jewish men arrested on the streets or in police raids on their apartments were kept in miserable conditions. A medical report on a group of labour camps at Belzec noted in September 1940 that the accommodation was dark, damp and infested with vermin. 30 per cent of the workers had no shoes, trousers or shirts, and they slept on the floor, 75 to a room measuring 5 metres by 6, so overcrowded that they had to lie on top of one another. There was no soap and no sanitation in the huts: the men had to relieve themselves on the floor during the night, since they were barred from going out. Rations were entirely inadequate for the heavy physical labour the men were required to carry out, mostly on road works and the reinforcement of river banks.

171

The deteriorating situation was calmly recorded by the Jewish schoolboy Dawid Sierakowiak in his diary. ‘The first signs of German occupation, ’ he noted on 9 September 1939. ‘They are seizing Jews to dig.’ Although school was starting, his parents stopped him attending because they feared he would be arrested by the Germans. Two days later he was reporting ‘beatings and robbings’ and noting that the store where his father worked had been looted. ‘The local Germans do whatever they wish.’ ‘All basic human freedoms are being destroyed,’ he noted, as the Germans closed the synagogues and forced stores to be open on a Jewish religious holiday. As his mother was obliged to queue for two hours at the bakery at five o’clock every morning to get bread, Sierakowiak reported that the Germans were taking Jews out of food queues. His father lost his job. Then the Germans closed Sierakowiak’s school and he had to walk five kilometres a day to another one because his family no longer had the money to pay his tram fare. By 16 November 1939 Sierakowiak was being forced, along with other Jews, to wear a yellow armband when he went out; in early December this was changed to a yellow, 10-centimetre Star of David that had to be worn on the right chest and the back of the right shoulder. ‘New work in the evening,’ he recorded, ‘ripping off the armbands and sewing on the new decorations. ’ As the first snows of winter began to fall, his school was closed down, and the textbooks were given to the pupils: ‘I got a German history of the Jews, a few copies of German poets, and Latin texts, together with two English books.’ Dawid Sierakowiak began to witness Germans beating Jews on the streets. The situation was deteriorating on an almost daily basis.

172

By the autumn of the following year, shocking scenes of violence against the Jews were taking place on the streets of many towns in Poland, including Szczebrzeszyn. On 9 September 1940 Klukowski noted:

This afternoon I was standing by the window in my room when I witnessed an ugly event. Across from the hospital are a few burned-out Jewish homes. An old Jew and a few Jewish women were standing next to one when a group of three German soldiers came by. Suddenly one of the soldiers grabbed the old man and threw him into the cellar. The women began lamenting. In a few minutes more Jews arrived, but the soldiers calmly walked away. I was puzzled by this incident, but a few minutes later the man was brought to me for treatment. I was told that he forgot to take his hat off when the Germans passed by. German regulations require that Jews must stand to attention and the men have to take their hats off whenever German soldiers pass.

173

What Klukowski was witnessing was not just the arbitrary exercise of power by an invading force over a despised minority; it was the end-product of a prolonged process of policy-making in Berlin, aided by new institutional structures at the centre of the Third Reich that would play an increasingly important role in the coming years.

174

II

The Nazi plan for Poland initially envisaged three belts of settlement - German, Polish and Jewish - in three blocks, roughly western, central and eastern. Its implementation was by no means the exclusive prerogative of the SS: already on 13 September 1939, the Quartermaster-General of the Army Supreme Command ordered Army Group South to deport all Jews in the eastern part of Upper Silesia into the area that was shortly to be occupied by the Red Army. But it soon took on a more centrally directed form. The next day, Heydrich noted that Himmler was about to submit to Hitler an overall policy for dealing with the ‘Jewish problem in Poland . . . that only the Leader can decide’. By 21 September 1939 Hitler had approved a deportation plan that was to be put into effect over the next twelve months. Jews, especially those engaged in farming, were to be rounded up immediately. All Jews - over half a million of them - were to be deported from the incorporated territories along with the remaining 30,000 Gypsies and Jews from Prague and Vienna and other parts of the Reich and Protectorate. This, said Heydrich, was a step in the direction of the ‘final aim’, which was to be kept totally secret, namely the removal of the Jews from Germany and the occupied eastern areas to a specially created reservation.

In charge of the operation was the head of the SS Central Office for Jewish Emigration (

Zentralstelle f̈r j̈dische Auswanderung

) in Prague, Adolf Eichmann, who set to work energetically, securing the agreement of the relevant regional officials to the deportation plan, and setting up a transit centre at Nisko on the river San. A trainload of more than 900 Jewish men left Ostrava, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, on 18 October 1939, followed by another transport of 912 Jewish men from Vienna two days later. At Nisko, however, there were no facilities for them. While a few were detailed to start building barracks, the rest were simply taken a few kilometres away by an SS detachment and then driven off by the guards, who fired their guns and shouted at them, ‘Go over there to your Red brothers!’ The agreement reached by Himmler with the Soviet Union on 28 September 1939 for the transfer of ethnic Germans to the incorporated territories then put a stop to the whole action, not least because the transport facilities and personnel were needed to deal with German immigrants from the east. In any case, as Hitler pointed out, the creation of a large Jewish reservation in the Nisko area would undermine the future function of the area as a military bridgehead for an invasion of the Soviet Union. Eichmann’s grandiose scheme had come to nothing. The stranded Jews stayed where they were, supported by the Jewish community in Lublin, and living in makeshift shelters, until April 1940, when the SS told them to disband and find their own way home: only 300 eventually managed to do so.

175

The scheme was not regarded as a failure, however. It showed that it was possible to deport large numbers of Jews from their homes in the Reich and the Protectorate to the east, not least by disguising the murderous undertones of the action through the use of euphemisms such as ‘resettlement’ to self-governing ‘colonies’ or ‘reservations’. Eichmann was promoted to head Department IVD4 of the Reich Security Head Office, in overall charge of ‘evacuation’ and ‘resettlement’.

176

His failure to provide adequate facilities for the proposed reservation at Nisko was no product of organizational incompetence: it was intentional. Essentially, the Jews of Germany and German-occupied Central Europe were simply to be dumped there and left to fend for themselves. As Hans Frank remarked: ‘A pleasure finally to be able to tackle the Jewish race physically. The more that die, the better; to strike at the Jews is the victory of our Reich. The Jews have to feel that we’ve arrived.’ A report on a visit of leading officials of the General Government to the village of Cyc’w on 20 November 1939 commented: ‘This territory, with its strongly marshy nature, could serve as a reserve for the Jews according to District Governor Schmidt. This measure would lead to a major decimation of the Jews.’ After all, as a member of the German Foreign Affairs Institute reported from Poland in December 1939, ‘the annihilation of these subhumans would be in the interests of the whole world’. It was best, he thought, that this should be achieved by ‘natural’ means such as starvation and disease.

177

During the next few months, various alternative plans for the resettlement of the Jews of Central Europe were canvassed in the Reich Security Head Office, the German Foreign Office and other centres of power: all of them involved, implicitly or explicitly, the murder of large numbers of Jews by one means or another. In February and March 1940, virtually the entire Jewish community of Stettin, numbering over a thousand, was deported on Heydrich’s orders under such appalling conditions that almost a third of them died of hunger, cold and exhaustion en route. In the course of 1939, 1940 and the first four months of 1941, a series of uncoordinated actions led to the deportation of more than 63,000 Jews into the General Government, including more than 3,000 from Alsace, over 6,000 from Baden and the Saar, and even 280 from Luxembourg. None of these deportations had led to any systematic policy implementation on a larger scale; most of them were the result of the initiatives of impatient local Nazis, most notably the Regional Leader of the Wartheland, Arthur Greiser, whose ambition it was to rid his territory of Jews as fast as possible. The Nisko plan had been aborted, and the size and speed of population transfers in Poland scaled down under the impact of wartime pressures and circumstances. Yet despite all this, the idea of forcing the Jews of Central Europe into a reservation somewhere in the east of the country remained under discussion. As a first step, Hitler envisaged the concentration of all the remaining Jews in the Reich, including the newly incorporated territories, into ghettos located in the main Polish cities, which, he agreed with Himmler and Heydrich, would make their eventual expulsion easier.

178

The American correspondent William L. Shirer concluded in November 1939 that ‘Nazi policy is simply to exterminate the Polish Jews’, for what else could be the consequence of their ghettoization? If the Jews were unable to make a living, how could they survive ?

179

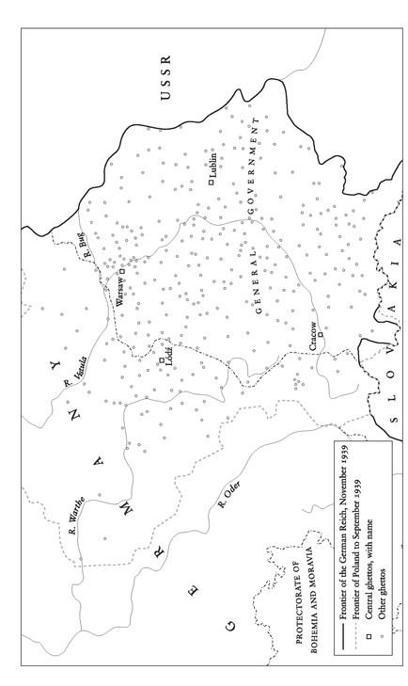

3. Jewish Ghettos in German-occupied Poland, 1939-44

III

Ghettos had already been discussed in Germany in the immediate aftermath of the pogroms of 9-10 November 1938.

180

Because few thought that the ghettos would have a long-term existence, no central orders were issued from Berlin for how they were to be managed. Heydrich proposed that Jews should be confined to certain districts of the main cities, but he did not suggest how. Conscious that his administration was far from prepared to accept and administer such a large influx of penniless refugees, Hans Frank tried to block the deportation of Jews from the Wartheland into the General Government, so Greiser took action on his own, within this general policy framework.

181

He ordered the concentration of the remaining Jews in the Wartheland into a ‘closed ghetto’ in the northern part of the city of L’d’, a poor district in which a considerable number of Jews were already living. On 10 December 1939, the regional administration drew up plans for the boundaries of the ghetto, the resettlement of non-Jews living there, the provision of food and other supplies and utilities, and other arrangements. On 8 February 1940 guards arrived at the boundaries and began erecting barriers to seal the area off. As Dawid Sierakowiak noted, mass arrests of Jews began in the city as early as December. ‘Everyone everywhere,’ he recorded, ‘has their backpacks ready packed with underclothes and essential clothing and domestic equipment. Everyone is extremely nervous. ’ Many Jews fled the city, taking what they could with them on handcarts.

182

By the time the ghetto was finally sealed off, on 30 April and 1 May 1940, it contained some 162,000 of the city’s original Jewish population of 220,000.

183

These people had to live in a district that was so poorly provided with basic amenities that over 30,000 dwellings were without either running water or a connection to the sewage system.

184

As a result, they soon seemed to confirm Nazi associations of Jews with dirt and disease.