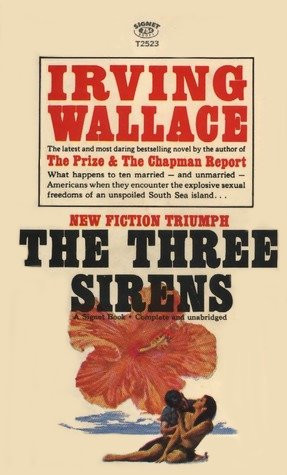

The Three Sirens

Authors: Irving Wallace

THE THREE SIRENS

Irving Wallace

First published by

Simon and Schuster

1963

THE THREE SIRENS

The Americans came to the long-hidden Polynesian islands of The Three Sirens as dispassionate observers. There were ten of them. The world-famous anthropologist, Dr. Maud Hayden. Her son and his beautiful young wife, Claire. A bachelor professor and film censor, attempting to flee his domineering mother. A warm, friendly, but quite unattractive nurse. A liberal-minded photographer and his wife, both of whom are anxious to remove their sixteen-year-old daughter from her fast adolescent crowd. The middle-aged wife of the expedition’s wealthy sponsor. And a female psychoanalyst whose private problems rival those of her patients.

On The Three Sirens, these visitors come face to face with uninhibited behavior—with customs that assault their most civilized defenses. The natives are unhampered by sexual restraint; they have learned to relieve the monotony of marriage, without guilt, to teach their young to love without fear. What this freedom does to the observers from another culture and how they are driven to a self-realization of their own fears and desires is the theme of Irving Wallace’s newest novel, a singular work of fiction that ruthlessly explores the innermost nature of modern man.

“Wallace burned up the bestseller list with The Chapman Report and showed a scholarly research effort in The Twenty-seventh Wife. In The Three Sirens, he combines the two with startling results.”

—MIAMI NEWS

By Irving Wallace

THE THREE SIRENS

THE PRIZE

THE TWENTY-SEVENTH WIFE

THE CHAPMAN REPORT

THE FABULOUS SHOWMAN

THE SINS OF PHILIP FLEMING

THE SQUARE PEGS

THE FABULOUS ORIGINALS

Dedicated to the memory of

my beloved friends

Zachary Gold

(1918-1953)

Jacques Kapralik

(1906-1960)

There is a scale in dissolute sensuality, which these people have ascended, wholly unknown to every other nation whose manners have been recorded from the beginning of the world to the present hour, and which no imagination could possibly conceive.

James Cook

Account of a Voyage

round the World

1773

At last, we are isolated from the outside world. Here, on these coral isles, which I have christened The Three Sirens, I will undertake my experiment…to prove, for once, that marriage as practiced in the West is antagonistic to human nature, whereas my System, blended with the Polynesian System, can produce a radically new form of matrimony infinitely superior to any known on earth. It will work. It must work. Here, far from the bigoted Throne and Censor, far from the accursed Peeping Toms of Coventry…here, amidst naked and unfettered Freedom … and with infinite Blessings of the Lord … my compleat System shall face the Test, at last.

Daniel Wright, Esq.

Journal

Entry June 3, 1796

I

IT WAS THE

first of the letters that Maud Hayden had taken from the morning’s pile on her desk blotter. What had attracted her to it, she sheepishly admitted to herself, was the exotic row of stamps across the top of the envelope. They were stamps bearing the reproduction of Gauguin’s “The White Horse,” in green, red, and indigo, and the imprint “Polynésie Française…Poste Aérienne.”

From the summit of her mountain of years, Maud was painfully aware that her pleasures had become less and less visible and distinct with each new autumn. The Great Pleasures remained defiantly clear: her scholarly accomplishments with Adley (still respected); her absorption in work (unflagging); her son, Marc (in his father’s footsteps—somewhat); her recent daughter-in-law, Claire (quiet, lovely, too good to be true). It was the Small Pleasures that were becoming as elusive and invisible as youth. The brisk early morning walk in the California sun, especially when Adley was alive, had been a conscious celebration of each day’s birth. Now, it reminded her only of her arthritis. The view, especially from her upstairs study window, of the soft ribbon of highway leading from Los Angeles to San Francisco, with the Santa Barbara beach and whitecaps of the ocean beyond, had always been esthetically exciting. But now, glancing out of the window and below, she saw only the dots of speeding monster automobiles and her memory smelled the gas fumes and the rotted weeds and kelp of the sea on the other side of the coastal road. Breakfast had always been another of the certain Small Pleasures, the folded newspaper opening to her its daily recital of the follies and wonders of Man, the hearty repast of cereal, eggs, bacon, potatoes, steaming coffee, heavily sugared, stacked toast, heavily buttered. Now, the hosts of breakfast had been decimated by ominous talk about high cholesterol and low-fat diet and all the linguistics (skimmed milk, margarine, broccoli, rice puddings) of the Age of Misery. And then, finally, among the Small Pleasures of each morning, there had been the pile of mail—and this delight, Maud could see, remained a constant delight, uneroded by her mountain of years.

The fun of the mail, for Maud Hayden, was that it gave her Christmas every morning, or so it seemed. She was a prolific correspondent. Her anthropology colleagues and disciples, afar, were tireless letter writers. And then, too, she was a minor oracle, to whom many came with their enigmas, hopes, and inquiries. No week’s grab bag of letters was without some distant curiosity—the one from a graduate student on his first field trip to India, reporting how the Baiga tribe nailed down the turf again after every earthquake; the one from an eminent French anthropologist in Japan, who had found that the Ainu people did not consider a bride truly married until she had delivered a child, and who had asked if it was exactly this that Maud had discovered among the Siamese; the one from a New York television network, offering Maud a meager fee if she would verify the information, to be used in a New Britain travelogue, that a native suitor purchased his bride from her uncle, and that when the couple produced an offspring, the infant was held over a bonfire to assure its future growth.

At first look, this morning’s mail, with its glued-in secrets, had appeared less promising. Going through the various envelopes, Maud had found the postmarks were from New York City, London, Kansas City, Houston, and similar unwonderful places, until her hand had been stayed by the envelope featuring the stamps with the Gauguin painting and the imprint of “Polynésie Française.”

She realized that she still held the elongated, thick, battered envelope between her stubby fingers, and then she realized that more often, in these last few years, her habit of direct action had been bogged down in musings and mind-wanderings clouded by a vague self-pity.

Annoyed with herself, Maud Hayden turned the long envelope over, and on the pasted backflap she found the name and return address of the sender, spelled out in a swirling, old-fashioned European calligraphy. It read: “A. Easterday, Hotel Temehami, Rue du Commandant Destremau, Papeete, Tahiti.”

She tried to match the name “A. Easterday” to a face. In the present, none. In the past—the efficient file of her mind flipped backwards—so many, so many … until the face captioned by the name was found. The impression was faded and foxed. She closed her eyes, and concentrated hard, and by degrees the impression became more definable.

Alexander Easterday. Papeete, yes. They were strolling on the shady side of the street toward his shop at 147, Rue Jeanne d’Arc. He was short, and as pudgy as if he had been mechanically compressed, and he had been born in Memel or Danzig or some port quickly erased by the storm troopers—and he had had many names and passports—and en route, the long way to America as a refugee, he had come to a standstill, and finally a residence and business, in Tahiti. He claimed to have been an archeologist in other years, accompanying several German expeditions in happier days, and had modeled himself after Heinrich Schliemann, testy and eccentric excavator of Troy. Easterday was too soft and grubby, too anxious to please, too unsuccessful, to play Schliemann, she had thought then. Alexander Easterday, yes. She could see him better: ridiculously perched linen hat, bow tie (in the South Seas), wrinkled gray tropical suit stretched by a potbelly. And yet better: pince-nez high on a long nose, an inch of mustache, cold dribbling pipe, and warped pockets bulging with knickknacks, notes, calling cards.

It was coming back fully now. She had spent the afternoon poking through his shop cluttered with Polynesian artifacts, all reasonably priced, and had come away with a pair of Balinese bamboo clappers, a carved Marquesan war club, a Samoan tapa cloth skirt, an Ellice Island mat, and an ancient Tonga wooden feast bowl that now graced the sideboard of her living room downstairs. Before their departure, she recalled, she and Adley—for she had wanted Adley to meet him—had entertained Easterday at the rooftop restaurant of the Grand Hotel. Their guest had proved an encyclopedia of information—tidbits illuminating the lesser puzzles of their half-year in Melanesia—and that had been eight years ago, closer to nine, when Marc had been in his last year at the university (and being contrary about Alfred Kroeber’s influence there simply, she had been sure, because she and Adley worshiped Kroeber).

Sorting the dead years now, Maud recollected that her last contact with Easterday had been a year or two after their meeting in Tahiti. It was at the time their study of the people of Bau, in Fiji, had been published, and Adley had reminded her to send Easterday an inscribed copy. She had done so, and months later Easterday had acknowledged their gift in a brief letter of formal appreciation mingled with genuine delight at being remembered at all by such august acquaintances—he had used the word “august,” and then she had possessed fewer doubts that he had been schooled at the University of Göttingen.

That was the last that Maud had heard of “A. Easterday”—the thank-you note of six or seven years ago—until this moment. She considered Easterday’s return address. What could that dim, half-forgotten face want of her now, across so many leagues: money? recommendation? data? She weighed the envelope in her palm. No, it was too heavy for a request. More likely, it was an offering. The man inside the envelope, she decided, had something to get off his chest.

She took the Ashanti dagger—a souvenir of the African field trip in those pre-Ghana days between the World Wars—from her desk, and in a single practiced stroke she slit the envelope open.

She unfolded the fragile airmail sheets. The letter was neatly typed on a defective ancient machine, so that many of the words were marred by holes—instead of an e or an o there was most often a puncture—but still all neatly, laboriously, efficiently single-spaced. She riffled through the rice-paper pages, counting twenty-two. They would take time. There was the other mail, and certain lecture notes to be reviewed before her late-morning class. Still, she felt the curious and old familiar nagging from the second self, the unintellectual and nonobjective second Maud Hayden, who dwelt hidden inside her and was kept hidden for being her unscientific, intuitive, and female self. Now this second self nudged, reminded her of mysteries and excitements that had often, in the past, come from faraway lands. Her second self only rarely asked to be heard, but when it did, she could not ignore it. Her best moments had come from such obedience.

Brushing aside good sense, and the pressure of time, she succumbed. She settled back heavily, disregarding the metallic protest of the swivel chair, held the letter high and close to her eyes, and slowly, she began to read to herself from what she hoped might be the best of the day’s Small Pleasures:

PROFESSOR ALEXANDER EASTERDAY

HOTEL TEMEHAMI

PAPEETE, TAHITI

Dr. Maud Hayden

Chairman, Department of Anthropology

Social Science Building, Room 309

Raynor College

Santa Barbara, California

U.S.A.

Dear Dr. Hayden:

I am sure this letter will be a surprise to you, and I can only hope that you will be kind enough to remember my name. I had the great honor of meeting you and your illustrious husband ten years ago, when you stopped over in Papeete several days, en route from the Fiji Islands to California. I trust you will recall that you visited my Polynesian shop in the Rue Jeanne d’Arc and were generous enough to compliment me on my collection of primitive archeological pieces. Also, it was a memorable moment of my life to be the guest of your husband and yourself to dinner.

Although I am out of the main track of life, I have managed to keep in touch with the outside world by subscribing to several archeology and anthropology journals as well as Der Spiegel of Hamburg. As such, I have read of your activities from time to time, and not without pride, I must admit, for having encountered you once. Also, through the recent years, I have acquired some of your earlier books in the more accessible paperbound editions, and I have read them with burning interest. Truly, I believe, and not I alone, that your brilliant husband and yourself have made the greatest of contributions to modern-day ethnology.