The Thrifty Cookbook: 476 Ways to Eat Well With Leftovers (2 page)

Read The Thrifty Cookbook: 476 Ways to Eat Well With Leftovers Online

Authors: Kate Colquhoun

Tags: #General, #Cooking

BOOK: The Thrifty Cookbook: 476 Ways to Eat Well With Leftovers

9.66Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Cooking with food that you might otherwise simply throw out makes sense in all sorts of ways. Creating something tasty from languishing fruit or vegetables, extending the life of fresh meat by using marinades, preserving gluts in jams or chutneys, or simply using up a bowlful of leftover meat, rice or pasta will not only save you money but also make a substantial environmental difference.

This kind of thrifty cooking is not about making an impression. It’s about being relaxed without compromising on quality and taste, the kind of cooking that you simply can’t be fetishistic about. This is not the place for purism or marvellous presentation. So that’s a relief.

The statistics of how much food we throw away are astonishing: 6.7 million tonnes a year and rising. That’s a third of all the food we buy, and enough to fill Wembley stadium to the brim eight times a year. Half of it is meat bones, teabags, eggshells and vegetable peelings but the other half could be eaten. We chuck out three times more than the total waste from supermarkets, which is not to say that the food industry and the public sector don’t have much to do – the food chain is still generating 11 million tonnes of waste – but it does put much of the responsibility for change back on our own doorstep.

We live in a world where half of us are killing ourselves with excess calories while the other half starve, in a society that spends more on dieting than on food aid and where health and safety legislation means that it is criminal to donate perfectly viable food that’s reached its use-by date to the homeless. And though we might get into a lather about food miles or the ethics of battery chickens, the amount of food we send to landfill each year is the skeleton in the cupboard. It’s only alarming when the bin bag breaks, disgorging its slimy contents all over the floor; the rest of the time we don’t notice.

There is, of course, a significant environmental cost to all this. In landfill sites, rotting food, airless in its black bags, creates methane – a greenhouse gas 23 times more powerful than carbon dioxide – and a poisonous black sludge that seeps into our watercourses. It’s estimated that if we just stopped wasting food, we could reduce our carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by at least 15 million tonnes a year – the same as taking one in every five cars off the road. This is far more than we could achieve by reducing food packaging or eliminating plastic bags.

Wasting food also costs hard-earned cash – something like £15,000–24,000 in a lifetime and worth around £10 billion a year, which is more than the UK’s foreign aid budget. Depressingly, around a quarter of it is chucked out in its original packaging: including 5,500 chickens and 1.2 million sausages, almost 4.5 million apples and only slightly fewer potatoes every day, plus around 328,000 tonnes of bread a year.

As a proportion of our income, food is cheaper than it has ever been – no wonder we value it less and are easily seduced into buying too much of it at once. But food prices are on the rise, driving inflation as fast as oil and gas prices. Climate variation is affecting traditional harvests around the world, while an exploding population means that our future ability to feed ourselves is in question: the UN warns that we need to increase world food production by 70% by 2050 to feed a population that will have risen from six to nine billion. So it’s not just about price – it’s also about hunger. Curbing the wasteful habits of the past century is more than a middle-class lifestyle choice. It’s critical.

Unlike most of our Continental neighbours or families in Asia and the Middle East, who still use up their food with imagination and without embarrassment to make two, four or even more meals, we’ve broadly lost the knack – perhaps the first generation to give up on taking leftovers and food past its best seriously. But returning to traditions of buying less, wasting less and honouring food and its production more shouldn’t be difficult. Price rises will feel less burdensome if you know you’re going to get several good meals out of what you buy, refusing – like granny – to waste a scrap.

This isn’t boring frugality – it’s about making food that tastes really good – think of Italy, where leftover dishes such as Ribollita, Arancini and Bread Salad or ‘Panzanella’ (see

pages 60

,

140

and

213

) are some of the finest in the repertoire. There’s no need to rehash the same old meat endlessly throughout the week any more than to collect the lard for greasing cartwheels. Actually, it

is

worth having lard around because there are times when it tastes better and works better than olive oil: roast potatoes are a case in point. But you don’t have to buy it – you can save the fat from a roast. Stock cubes and bouillon powders are fine, but there’s something really

good

as well as useful about a simple home-made stock. And it’s virtually free. Long after it’s lost its right to live on the breadboard, the last bit of bread can be used in puddings, salads or soups, or kept in the freezer as breadcrumbs to use in meatballs or as the crunchy top of a bake, zesty with lemon and pungent with garlic and herbs.

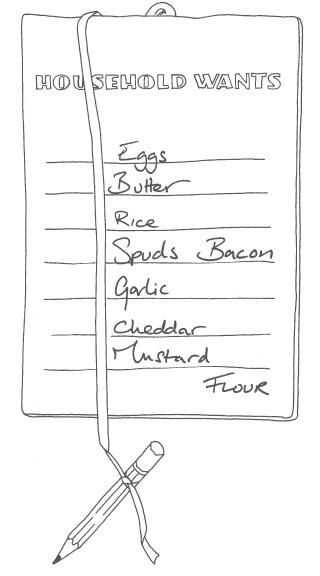

Cooking with leftovers in delicious, imaginative and easy ways and using up raw food that would otherwise be thrown away is a vital part of the continuum for anyone who cares about their food. I have to say that much of what follows in this book might seem like stating the bleeding obvious – that fresh herbs and good spices are essential components of making food tasty; that one simple extra ingredient from a store cupboard or picked up on the way home can transform all the bits in the fridge that need to be used up; that meat that’s already been cooked is not going to give up any more juices; that you can do different things with leftovers depending on how much you have to work with. But bear with me. This kind of cooking is also, often, about inverting the normal scheme of things. Instead of being seduced by a new recipe and then rushing out to get the ingredients, you’ll be looking at what you have to hand and then deciding what kind of taste and texture you want and what kind of cooking you’re in the mood for: a soup, pie or stir-fry, a salad, stew or bake? Sometimes – as with meat in stir-fries – the method will completely reverse the usual way of doing things and, except when you are making pastry or baking cakes, precise measures are not going to matter.

In some ways, recipes themselves are suspect, because this is all about practicality and imagination. Most of these recipes work on rough amounts – a British teacupful (about 175ml) of meat per person, say, for a pie – and they describe basic processes that can be endlessly varied, with lots of ideas on how you can change things about. Meat, for example, can be omitted from almost any recipe and replaced with vegetables that are crying out to be used up. To help get you started, I’ve included a basic list of the kind of flavours that go together well (see

pages 26

-

7

). The knack is to taste and taste again as you cook, altering the combinations of herbs and seasonings and developing the recipe ideas in the pages that follow to suit your own style.

Thrifty cooking is not about bland and colourless dinners for the sake of saving a chicken wing. With fresh cream in just about every corner shop, olive oil on every shelf and inspiration flooding in from all corners of the globe, there need be nothing plain about this food – nothing stopping it from being as good (or better) than it was the first time around. I bet most of us have got the Christmas leftover thing taped through sheer force of practice, and this book is really just an extension of that. With a bit of planning, a thoughtful array of cupboard staples, judicious use of space in the freezer and experimentation with what goes with what, using up food properly can become something of an addictive habit. The last carrots in the fridge can be transformed into a curried pickle that will enliven a basic pilaf, a couple of blackened bananas make a lush banana cake, while a lingering single egg white is easily whisked into a meringue that will keep in a tin for weeks, if you’ve got that kind of self-control. Taking these recipes as a guide, you can eke out several good meals from one big roast – conjuring ‘free’ food out of what, yesterday, you might have considered rubbish.

Other books

Activate by Crystal Perkins

Imperative Fate by Paige Johnson

A Curious Beginning by DEANNA RAYBOURN

Miss Goldsleigh's Secret by Amylynn Bright

The Midnight Sea (The Fourth Element #1) by Kat Ross

With This Ring by Amanda Quick

The Killing Club by Paul Finch

Autumn: Aftermath by Moody, David

Carry the Light by Delia Parr