The Time Tutor (12 page)

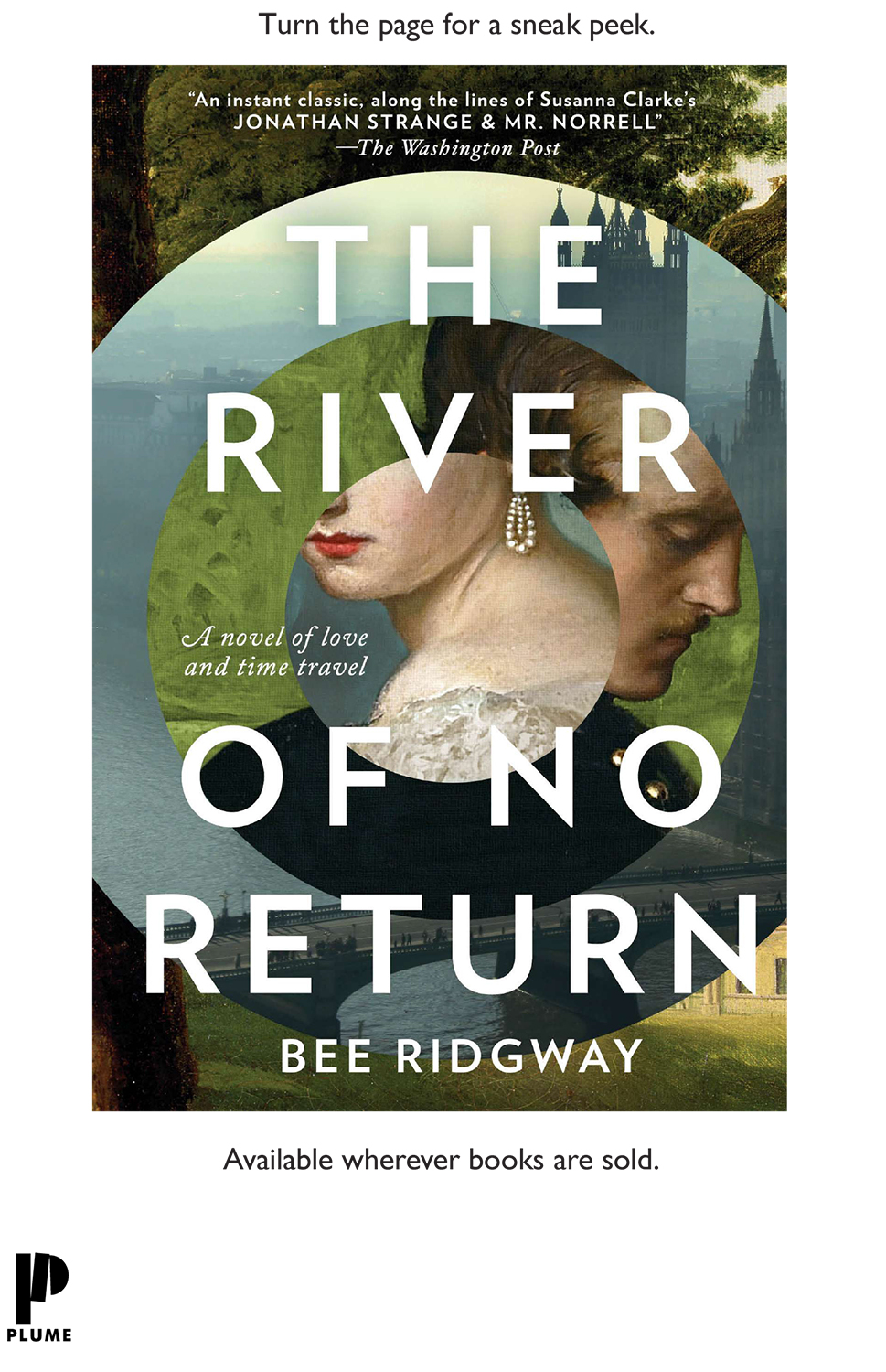

Authors: Bee Ridgway

“I do not have to give you my reasons.”

Hannelore yanked Alva toward her, then dropped her ear and instead took her face between her hands. Her blue eyes seared. “How could you steal my beautiful secret?” Hannelore whispered. “How could you spill it, here, in this perfidious era? Among these ghosts and shadows?”

Alva opened her mouth to answer, but at that moment someone in the audience found his voice, and hollered, “Go home, Miss Havisham! Let the girl have her fun!”

With his voice, the ballroom came to life again. There were shouts of agreement, and the trombonist made another sally with his slide. Then the bandleader called across the crowd, “Out with the old, in with the new! âLet's All Go to Mary's House!' One, two, three, four!” The band struck up, dancers began to kick and spin, and a brace of waiters started making their way toward Alva and Hannelore with the clear intention of escorting them out of the ballroom.

It was then that Alva felt the River open like a whirlpool beneath her, all the depth of time at once, the theater and the hospital and the fire and the palace, and all the emotions of tens of thousands of Londoners living and loving and dying here in this place for a thousand years. Hannelore had slid one hand round Alva's neck, to grip her by the nape. She began dragging Alva with her, and the River was draining her away with Hannelore into the past. “You will come with me,” Hannelore said. “You will come home with me and we shall forget this interlude.”

“No.” Alva twisted out of Hannelore's grasp

and with all the strength of her will she wrenched her soul from the terrible pull of the River. She held a hand out, warning Hannelore to keep back. “Do not touch me again.”

The Alderwoman's eyes widened in surprise, then narrowed in rage. “Who has taught you? Who has taught you to do this thing?”

“No one,” Alva said. “I taught myself.”

“That is impossible.”

“You withheld it from me, but I found it, and I took it. I found it within myself.”

Hannelore lunged for her, and at the moment of touch, Alva felt herself tumbling through time's whirlpool once again. “I will find out the truth from you; I will drag it from you.” Hannelore's voice filled Alva's head.

“The truth is that you will steal my youth and give me nothing in return!” Alva twisted in her fall through time, desperately urging her talent to catch her, to hook her up and back to the ballroom. “I hate you.” She spoke the words directly into Hannelore's face. “I hate you, and I want to be free of you.”

Everything stopped. They were suspended, as if between worlds. It might be any time, any time at all. Alva watched as the love that she had once so desperately wanted, the love that she had cultivated in Hannelore, died away in the old woman's eyes.

Then they were standing face-to-face, firmly planted on the dance floor. “Let's All Go to Mary's House” was still in full swing.

Hannelore was flanked by waiters now, one of whom was plucking at her sleeve. She shook him off. “Alva Blomgren.” Her voice was perfectly calm. “I cast you out of the Guild. You are dead to me. You have rejected my protection and dared to make your way in this world alone. So be it: Alone you will remain and if you should ever come crawling back to me, I shall spurn you like a dog.”

Hannelore raised her chin, cast one last look at Alva, and then simply disappeared.

The music stopped.

The screaming started.

But Alva, in the midst of the panic-stricken ballroom, found that she was smiling.

The future had begun.

Castle Dar, Devon, 1815

J

ulia sat beside her grandfather's bed, holding his hand. The fifth Earl of Darchester was dying.

Heavy velvet curtains were drawn across the tall windows, but the late-afternoon sun found a thin opening and as the day grew older a narrow ribbon of light moved slowly across the floor and over the bed. Lord Percy's breath was shallow. Julia felt life guttering in his fingers, saw death written on his beloved face. Motes of dust moved slowly in the shaft of light. Once Grandfather was dead, Cousin Eamon would be the new earl and would live here, at Castle Dar. Julia sighed, making the dust dance with her breath, then squeezed her eyes shut, willing herself to be calm. Time enough to worry about tomorrow's problems.

The house was almost completely silent, except for Grandfather's painful gasps. The sun inched up the counterpane, touching their fingers now.

The sound of hooves and jangling harness broke the spell. Julia went to the window and pushed aside a swathe of curtain with the back of her hand. Far away across the lawn, where the long drive disappeared into the wood, she saw a tired old traveling coach, piled high with luggage and drawn by a team of broken-down job horses, lurching toward the house.

“Is it Eamon?” The voice from the bed was little more than a whisper.

Julia turned back, letting the curtain fall. “Yes.”

Lord Percy closed his eyes. “I will be dead before the sun goes down. Why couldn't he wait until morning?”

“Because he is cruel.” Julia walked back to the bed.

Only a few weeks ago Grandfather had been as hearty as an oak. But the disease that was wasting his flesh had progressed with terrifying speed. And now here was Eamon, rushing to gloat over a dying man.

Lord Percy's hand moved anxiously on the counterpane, as if searching for something.

Julia caught it. His fingers were terribly cold. “What do you need?”

He swallowed, then whispered. What he said clearly pained him. “I can no longer protect you.”

Julia sat on the bed, raising the hand she held and kissing the knuckle above the emerald ring that once looked right on a strong hand but now seemed too big. “It is you he has tormented all these years. I mean nothing to him.”

His fingers tightened around hers. “It isn't only Eamon. There may be others. Julia . . .” He raised his head, and his whispering grew harsh. “Tell no one anything. No one at all. You must pretendâ”

“Hush.” Julia pressed his palm to the counterpane, and his head fell back against the pillows. She bent and stroked his high forehead. “I have nothing to tell. I have no secrets.”

“You have no secrets, because you don't

know.

” His fierce gaze softened; he let out a long shuddering sigh and closed his eyes. “I am a fool,” he said. “A blind fool.”

“Hush now.” The sound of the approaching carriage was getting louder. “You must remain calm. He is coming.”

His eyes fluttered open. “If only I had time.”

“You have had your share of time, old man.” Julia smiled.

His lip twitched, the shadow of a grin. “I am greedy.”

“It's not a nice trait.” She smoothed one of his eyebrows with her thumb.

“I have never been nice. I have taken what I wanted. Time, money, women.” His voice took on some of the volume it used to have when he would thunder through the house, and he raised himself to one elbow. “I have lived my life! But I have never sniveled and whined. Always I have taken what was given willingly, or I have paid with money or passion or blood. . . .” He collapsed back against his pillows. “I hate this blasted dying!”

Julia let her fingers rest against his sunken cheek. “So do I.”

Together they listened to the carriage drawing close, a growing percussion beneath the old man's labored breathing. They heard the wheels hit the bump just before the driveway split to curve in front of the house. Julia's stomach clenched; soon Eamon would be in this very room.

“Julia?”

“Yes?”

His cheekbones and his nose were sharp; it was the look of death. “Let's speed the time. Let's outwit him. Just once more.”

“Do you have the strength?”

“Yes, yes. I shall twist time to my own ends and then . . .” He paused and tremblingly tucked a strand of hair behind her ear. “Then you shall be orphaned after all.”

Julia bit the inside of her cheek, tamping down the tears. He would never do that again, that little motherly gesture.

He let his hand fall from her face. “I had hoped . . .” He sighed. “Well. The angels must watch over you now.”

“Religion, Grandfather? At the eleventh hour?”

“Ha!” He flashed her a real grin then, the irrepressible, scapegrace expression that she loved. “It is not the eleventh hour, my dear. It is a minute or two before the twelfth. And those minutes crawl. We must bid them gallop. Come. Let us play, my little foundling. My darling one.”

Julia's tears spilled over then, and she didn't care. “One last time.”

“Good girl.” His hands fluttered, and she took them both in hers. The sliver of light streamed between them, illuminating their fingers.

“Watch the dust, there in the light. Watch as I make it dance, my poppet.”

Together they focused on the dust. Julia felt her grandfather's great power, felt how he willed the dust to dance. At first it only shivered, then it began to move faster and faster until it seemed to blow like snow in a blizzard. In the light on either side of them, the dust moved as slowly as it ever had. Lord Percy's eyes blazed, then broke focus. His fingers clasped hers strongly, then released. He fell back with a choked cry.

The dust slowed immediately, and Julia was left gripping hands that responded not at all to her kisses and tears.

Eamon Percy, now the sixth Earl of Darchester, threw open the door to find Julia pressing her grandfather's palm to her wet cheek. The old man's head was thrown back, his dead face grinning defiance.

Hartland, Vermont, 2013

Nick was on his way into town when the text came through from Tom Feely: “get here now cheese inspector.”

Nick pulled a youie, then made a sharp right onto Densmore Hill Road. It was a cold December and the hill would be hard going, but Nick had chains on his tires. He'd get to the farm in time to charm the inspector.

The pickup crested the hill with a groan and Nick patted the dashboard. The sky was a thin blue and the bare trees shivered resentfully in the wind. Still, the view out over the snowy valley struck Nick much as it had the first time he'd seen it on a glorious fall day four years ago: This corner of Vermont was a place he could learn to call home. He let the good feeling in and burst into a loud rendition of “The King Shall Enjoy His Own Again.”

Down below him, Thruppenny Farm hugged the base of the hill like a child trying to hide in its mother's skirts. Nick could see the red barns with their thick caps of snow, and the barnyards, tramped to mud by the forty Guernsey cows that Tom Feely kept for his artisan cheese business. Nick bellowed as the truck picked up speed: “âThen let us rejoice, with heart and voice! There doth one Stuart still remain!'”

Nick downshifted and eased around the last curve. He was happy to play lord of the manor for the elderly cheese inspector, who was a dyed-in-the-wool Anglophile. The visits were always the same. The old man would greet him with shy deference, they would chat for a few minutes about the queen or crumpets, and then they would go into the cheese-making room, and from there into the smaller cheese cave. Immediately on the left were the shelves dedicated to raw-milk Bries and Camemberts, cheeses yielding enough to melt a heart of stoneâand entirely against the law. The inspector would pass them right by, saying something like, “English cheese! People go on and on about French-style cheeses but they don't even exist for me. No, I don't even see them. Give me a good, firm English cheese every time. Isn't that right, Mr. Davenant?” His eyes would twinkle at Nick, and Nick would murmur his agreement. Then the inspector would linger over the shelves of stolid Cheddars, aged enough to be lawfulâthe prize-winning truckles for which Thruppenny Farm was becoming famous.

Nick didn't mind indulging the old man with a touch of Merrie Olde. It had been so very long now since Nick had been home that he took a guilty pleasure in following the cheese inspector to his green and pleasant fairyland. And Tom had nothing to complain of. For nigh on four years the inspector had given Thruppenny Farm top marks in every category, signing off on his list of checkboxes even as the seductive funk of bloomy rinds filled his nostrils.

Nick parked nose to nose with Tom's Methuselah of an old Farmall tractor, its pigeon-toed front wheels capped with snow. Downgrading his song to a whistle, Nick swung out of his pickup, shoved his hands into the pockets of his coat, and walked into the barn. The sweet smell of well-tended animals and hay hit his nose. He stood for a moment breathing it in while his eyes adjusted to the dim light. Tom usually waited for him here, but aside from the cows shifting in their stalls and an insinuating cat making free with his ankles, there was no one around.

Then he heard the distant clank of metal against metal and realized Tom must already be in the cheese room. He went out the barn's back entrance and across to the small, new building with the stainless steel door. It opened into a vestibule where Nick took off his boots, fished a pair of Crocs out of the tub of disinfectant, shook them vigorously, and pushed his thick-socked feet into them. He opened another stainless steel door into the brightly lit cheese-making room, the heart of this farm and Tom Feely's pride and joy.

Tom was there, heaving the illegal cheeses out of the cheese cave and into a big plastic trash can that he'd clearly dragged in from the barn; it was far from clean.

“What the hell?” Nick stared as Tom hurled a particularly gorgeous wheel of Brie down into the mess. It burst open like a smashed melon.

“New cheese inspector,” Tom said over his shoulder, already reaching for another wheel.

“Shit.” Nick pitched in. This was serious. Only last summer a dairyman in the next county had been led away from his farm in leg manacles by machine gunâtoting FDA officials, for the crime of making unpasteurized cheese. Jailed for months. Nick put some effort into it, scooping up two wheels at a time. A new cheese inspector would want to flex his muscles. Make a name for himself.

In a minute more the shelves in the cave were bare of the beautiful, tender wheels that Tom Feelyâa hatchet-faced man who wore his Purple Heart pinned to his Red Sox capâcould not and would not stop making. “I was born to make Brie,” he said of himself. “And I was born to make it right.”

Together Tom and Nick dragged the heavy trash can out and behind the barn, and Tom covered the voluptuous ruination of a month's hard work with a hay bale. The scent of hay and cheese together was so good that Nick actually felt tears behind his eyes. “By God, Tom, that's the saddest thing I've ever seen.”

“There's always more milk and more time.” The farmer crossed his arms over his chest and stared up the driveway, waiting for the inspector.

The two men had met on the day that Nick had first seen the view from the top of the hill, a mere ten minutes after he had first fallen in love with Vermont. Thruppenny Farm had been on the market, and Nick had pulled in when he'd seen the

FOR SALE

sign in the yard. Tom gave him a tour. The farm had been in Feely hands since the Revolution, but as Tom told Nick that day with a shrug, “Nothing lasts forever.”

Nick knew a good soldier when he met one. He assumed that selling the farm felt quite a lot like dying to Tom Feely, and he also assumed that Tom would rather die than show those emotions. But Tom was an American, and sometimes Nick thought he would never really understand Americans. They were deceptively simple. Tom might have been feeling anything at all under that baseball cap.

The tour had ended in the state-of-the-art cheese-making room and cheese cave. Nick had watched as Tom bent and looked closely at a broad-shouldered, cloth-wrapped Cheddar, his hand resting on its mottled surface. Tom straightened again and closed his eyes, the better to sense through his fingers. He was figuring out if time had done its work. It was as if Nick wasn't there at all.

Nick made his proposition without thinking, before Tom had lifted his hand away from his cheese. And so Nick became the owner of a small Vermont dairy farm. The Feelys paid him a nominal rent and kept him in legal and illegal milk products. For himself, Nick had ended up buying a house a few miles away. Since then he had bought up a few more struggling farms, and he had four families under his guardianship. Nick spent most of his time in Vermont and was considering abandoning New York altogether.

But now there was a new cheese inspector, and one almost certainly less susceptible than his predecessor to the charms of a plummy British accent.

“Here we go.” Tom straightened his blue and red baseball cap on his head, and Nick noticed how his fingers lingered for a split second on the Purple Heart.

Owner and tenant stood side by side, watching as an old white BMW E21, streaked and spotted and marbled with rust, turned into the farmyard.

â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â

It was the feeling of itâas if Nick's saber were an extension of his own body. As if it were his own hand he was thrusting into the young man's neck, as if it were his nails ripping through the soft flesh, catching on the tendons, pulling, then slicing through. The man's eyes, staring with a sort of blank surprise as red blood spilled richly over his blue uniform. Black eyes and red blood. The saber withdrawing, as if it were Nick's own arm he was pulling back, pulling awayâand now he was flying away, backward, into a tunnel of smoke . . . he was being sucked away at hideous speed, and at the distant end of the tunnel the splash of red and the young man's face fixing in death. . . .