The Tokyo Zodiac Murders (5 page)

Read The Tokyo Zodiac Murders Online

Authors: Soji Shimada

“What kind of lesson?” Kiyoshi asked, missing my sarcasm. “I have a keen sense of morals—unlike him. Enough of the general introduction. Let’s get down to the details of Heikichi Umezawa’s murder.”

“Certainly. I’m an expert on that!”

“Are you indeed?” said Kiyoshi with a grin.

“Yes. I learnt everything by heart, so you can have the book… Oh, wait… Keep the page that has the floor design.”

Kiyoshi yawned. “Ah, I just wish I didn’t have to keep listening to your boring lecture, but go on, go on…”

That was typical Kiyoshi. I ignored him and continued. “At noon on 25th February, Tokiko left the Umezawa house to visit her mother. She returned around 9 a.m. the next morning, the 26th. Now please keep in mind the fact that on that day in history—besides the attempted coup—there was a record snowfall in Tokyo, the heaviest in thirty years. After Tokiko got home, she prepared breakfast for her father. He always ate whatever she cooked, because he trusted her and, among other things, she was his real daughter.

“Tokiko carried breakfast to the studio a few minutes before 10 a.m. She knocked on the door, but he didn’t answer. She walked to the side of the studio and looked through the window. She could see her father lying on the floor in a pool of blood.

“Tokiko was horrified. The door was locked, so she rushed back to the main house and got the other women to help break the studio door down. Heikichi was dead. The back

of his head had been crushed by a blunt object, possibly a frying pan. It was determined that his death was due to brain contusion. Bleeding could be seen from his nose and mouth. There was some money and valuables in his desk; but nothing seemed to have been stolen. His bizarre note, which was written in a notebook, was found in the drawer.

“Eleven paintings—which Heikichi called his life’s work—were standing against the north wall. There was no damage to any of them. A twelfth painting remained unfinished on an easel. Coals were still glowing in the heater when his daughters broke into the studio. Detective stories were popular at the time, so they knew not to disturb the crime scene. The police soon arrived.

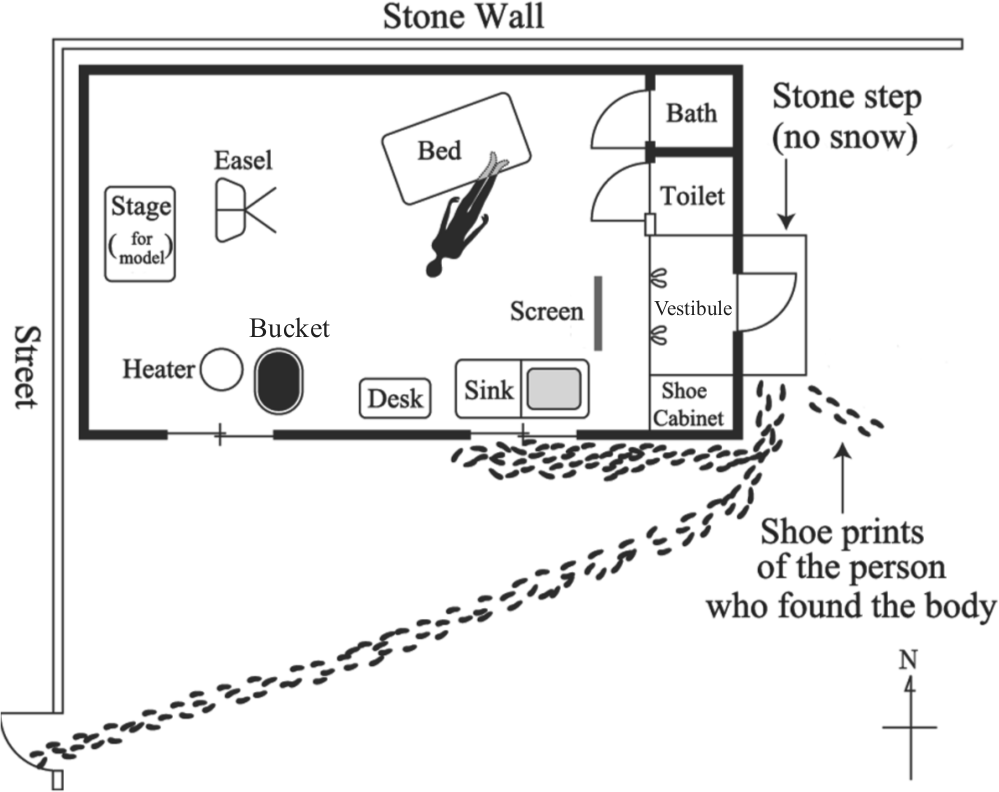

“As I said, Tokyo the previous night had had the heaviest snow in thirty years. Now please look at the second illustration.”

“Between the studio and the gate, some footprints in the snow were clearly visible. They were the shoe prints of a man and a woman—or at least a man’s shoes and a woman’s shoes. Whatever their gender, it would seem the two people did not walk out from the studio together. And they certainly didn’t walk side-by-side. Their prints overlapped.

“True, they might have left the studio at the same time, one following behind the other. But the man’s shoe prints led out of the studio to the window above the sink on the south side, where it appeared he walked back and forth, while the woman’s shoe prints lead straight from the door to the gate. If the two people left the studio at roughly the same time, the man left the studio slightly after the woman. In fact, he stepped over her prints. Beyond the gate to the property, the street was paved. At the time the police arrived, both sets of prints ended there.

“The duration of the snowfall is the key point. In Meguro, snow started to fall at about 2 p.m. in the afternoon of 25th February. It seldom snows in Tokyo, and the system for forecasting weather was obviously not as sophisticated as it is today, so no one had any idea how much snow would accumulate. In fact, the snowfall continued until 11.30 p.m.—a total of nine and a half hours of snow. Then, the next morning, at 8.30, it snowed again lightly for about fifteen minutes.

“You can see how the second snow would have left only a light dusting on the shoe prints. Therefore, the two people had to have entered the studio at least thirty minutes before the snow stopped at 11.30; and the woman, followed by the man, left sometime between 11.30 at night and 8.30 in the morning. The reason I say they entered the studio thirty minutes

before the snow stopped is because their prints were covered with snow but not fully obscured.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Now, there had to have been three people in the studio that evening: whoever left the man’s shoe prints; whoever left the woman’s shoe prints; and Heikichi Umezawa himself. It seems highly unlikely that the man killed Heikichi after the woman had left. But if the man did kill him, the woman must have seen who he was. Likewise, if the woman killed him, the man would have seen who she was—but it couldn’t have happened that way, because he left the studio after her. Presumably he wouldn’t have watched her kill Heikichi, nor would he have remained in the studio after the murder—nor would he have been walking back and forth between the south window and the door.

“But, supposing that the two were accomplices, there is the odd detail of the sleeping pills found in Heikichi’s stomach. The dose was far from a fatal one, so he must simply have taken the pills to fall asleep. Then after he took the pills, he was killed. But would he have taken the sleeping pills while entertaining his two visitors? Unlikely, eh?

“So could the crime have been committed by the man after the woman left? That, too, isn’t likely. Heikichi was not very comfortable around men; he had no close male friends. He felt secure around women, and if he was going to take some pills in the presence of anyone, it’d be a woman. And that didn’t happen because the woman would have already gone. In any case, no one’s been able to make any sense of the sleeping pills.

“What we come down to is this: whoever it was that left the man’s shoe prints was the killer, and whoever it was that left

the woman’s shoe prints witnessed the killing. So, Kiyoshi, who do you think was the person in the woman’s shoes?”

“His model?”

“Yes, very good! She could well have been a model, and she could well have witnessed the killing. The police made several public announcements, asking the model to come forward, promising her privacy would be protected. She never appeared. Nobody knows who the model was, even today, forty years later.

“But if a model was in Heikichi’s studio at 11.30 at night, then another mystery presents itself: would a model be working as late as that? If she was, then she must have been very close to Heikichi. No woman would work that late otherwise; in those days even daytime jobs for women were scarce. Of course, she might have been waiting for the snow to stop. And it’s true that there was no umbrella in the studio. But Heikichi was certainly capable of walking to the main house to get one.

“Many, however, have doubted the existence of the model at all. The police couldn’t produce her, that’s for certain; what’s more, they think the shoe prints were just a ruse. The only established fact was that whoever left the shoe prints walked from the studio to the street, not the other way around. That was determined by the way the snow was disturbed. And the prints were made in one pass. The possibility that someone could wear a pair of shoes on his or her hands and walk like a dog was also examined. The conclusion: impossible. The uneven distribution of the weight would have made it obvious.

“Anyway, enough about the question of shoe prints—which is far from the most interesting aspect of Heikichi’s murder. As he mentioned himself, he’d installed iron bars over his windows and skylights. He was a cautious man. The bars had not been

tampered with in any way. For security purposes, they had been designed to be removed from the inside.

“Therefore, there was only one way to enter the studio, and that was through the door. The killer had to come and go through the door. Actually, the door was unusual in itself: it was a Western-style, single-panel door that opened outwards, and it had a bar to secure it inside. Apparently, Heikichi had seen doors like that at hotels in the French countryside and he had ordered one for his studio. To lock the door, you had to slide the bar and insert it into a hole in the door frame. The bar had a small tongue that had to be turned downwards over a projection on the door. This projection had a ring, fastened by a padlock.”

Kiyoshi suddenly opened his eyes wide, raising himself up on the couch. “Really?” he said.

“Yes. And Heikichi was killed behind a locked door!”

“No, that’s not possible,” Kiyoshi said. “The killer would have had to escape through a secret passage!”

“You’re right. But the police checked everywhere. There was no other way out, short of the killer diving into the toilet and exiting through the pipes! Also impossible.

“Now, in the studio itself, two curious things were discovered. First, Heikichi’s bed was not against the wall as shown in the illustration. We know he liked to move his bed around, so that in itself was not so unusual—but it could still be an important clue. The other thing was that Heikichi had always had a beard. But when his body was found, his beard was partly cut off. From the look of things, he didn’t do that himself; it was done by another person—with a pair of scissors. Some whiskers from his beard were found near the body, but there were no scissors or razor in the studio.

“Now Heikichi and his brother Yoshio looked so much alike they could have been twins, and there was a rumour that the dead man was really Yoshio. Perhaps—for whatever reason—Heikichi had invited his brother to his studio, killed him, and then left, or vice versa. However, no one takes this idea seriously. Yoshio, moreover, never grew a beard. Yet it is still possible that family members misidentified the corpse. They had never seen Heikichi without a beard, and his head had been crushed. So misidentification can’t be excluded

altogether. Heikichi was such a maniac about his art, it seems he would have done anything to create Azoth.

“Well, that’s all that’s known about the circumstances. Shall we move on to the alibis of the possible suspects?”

“Just a minute…”

“What?”

“Your explanation is too fast! You’ve given me no time to contemplate the facts.”

“You’re kidding me!”

“No. I want to know more about Heikichi being locked in. Has as much thought been given to that as to the mystery of the shoe prints?”

“Well, forty years’ worth anyway.”

“Tell me more about the studio.”

“OK. I hope I can recall all the details. The roof of the studio was as high as a two-storey house, so even if the bed was stood on end, no one could reach it. What’s more, the skylights had iron bars over them. There was no ladder. The heater had a tin chimney, but it was too fragile to climb up—even Santa Claus couldn’t have done it! Besides, the coals were still burning in the heater. There was a hole in the wall to attach the pipe, of course, but it was smaller than your head. That’s about all I remember. There really was no other way out of the studio.”

“Were there curtains on the windows?”

“There were some, yes. And a long pole used for opening and closing them was found near the bed at the north side of the studio, a long way from the window.”

“Uh-huh. And the windows were locked?”

“Some were, but some weren’t.”

“How about the window above the spot where the man’s shoe prints were found?”

“It wasn’t locked.”

“I see. And what else was there in the studio?”

“Not much else, as you can see from the illustration. A desk, some paints and pigment, some pens, the notebook that Umezawa wrote his note in, a wristwatch, some cash and a map. I think that’s all. There were no books, magazines or newspapers, and no radio or phonograph. When he was in his studio, Umezawa didn’t want any worldly intrusions.”

“I see the wall of the property had a gate. Was it locked?”

“It could be locked from the inside, but the lock had been broken. It could be wrenched and opened easily from the outside.”

“Not very safe.”

“No, not safe. Oh, and at the time he was killed, Heikichi was emaciated. He suffered from insomnia and didn’t eat much.”

“Hmm. He was weak and in a locked room… And he was killed from behind by someone who didn’t even try to make it look like a suicide. Now, Kazumi, why do you think the killer locked the studio?”

I was prepared for this question. “Well, think about the sleeping pills,” I replied. “When Heikichi took them, he had either one or two visitors. So you have to figure that at least one of them was not a stranger.”

“Hmm. Did he have any friends?”

“There were a few artists he met in the De Médicis gallery and some customers at the small bar called Kakinoki. He went there quite often and got to know two regulars: Genzo Ogata, who was the owner of a mannequin factory, and Tamio Yasukawa,

one of Ogata’s employees. But they were not particularly close friends. Another acquaintance sometimes visited the studio, but you couldn’t call him a close friend, either.”

“What about Yoshio? Or Heitaro? They knew Heikichi pretty well.”

“Their alibis checked out, although they didn’t have many witnesses. On the night of the 25th, Heitaro played cards with his mother Yasue and some friends who came by after the doors of the gallery were closed. The guests left at 10.20, and mother and son went to their bedrooms upstairs at about 10.30. If Heitaro was the killer, he would’ve had to speed over to Heikichi’s studio in thirty or forty minutes to do the deed. Even without snow, it’s hard to get from Ginza to Meguro that fast; in heavy snow, it’s impossible. However, if Heitaro had conspired with Yasue to kill Umezawa, they might have bolted out of the gallery right after their friends left. So they could have made it within the presumed time frame of the murder. But what would have been their motive? Heitaro might have resented Heikichi—if he was his father—for his irresponsibility and the agony he had caused Yasue. Yasue, on the other hand, had no reason to hate Heikichi; she was quite close to him, and they were business partners. And she was his art dealer. Heikichi’s paintings sold for very high prices after his death, especially after the end of the war. Yasue had no contract with Heikichi, so she didn’t profit—and wouldn’t have profited—from his death.”

“Uh-huh.”

“As for Yoshio, Heikichi’s brother, he left for Tohoku on 25th February, and came home on the 27th around midnight. At the time of the murder, he was on his way to meet friends

in Tsugaru; there was no doubt that he had travelled there. It’s a long story; I’ll spare you the details. He had an alibi, but—as with several other possible suspects, especially the females—it wasn’t airtight. Yoshio’s wife, for example. While her husband was away and her two daughters were staying with Masako, she was alone. She had no alibi.”

“What if she was the model?”

“She was forty-six at the time. Would Heikichi have been inclined to paint a middle-aged housewife?”

“Hmmm…”

“Then there was the eldest daughter, Kazue. She was divorced and living alone in Kaminoge, which was a rather remote town at that time. She also had no alibi. Masako was in the main house having dinner with Tomoko, Akiko and Yukiko—her daughters—and Reiko and Nobuyo—her nieces. At 10 p.m., they all went to bed. And Tokiko was at her mother’s house in Hoya.

“Now the main house had six bedrooms, in addition to the kitchen and living room, which is where the daughters practised their ballet and piano. Masako, Tomoko and Akiko had their bedrooms on the ground floor. Upstairs, Reiko and Nobuyo shared the room nearest the stairs, the next was Yukiko’s, and the other one Tokiko’s. Heikichi essentially lived in his studio.

“Any one of the women could have sneaked out of her room at night, but there were no shoe prints around the main house. If they had gone out to the street from the front door, they could have walked around the property and entered through the back gate. Tomoko rose early on the 26th and said she shovelled the snow off the stone steps. She said there were only the shoe prints of the newspaper delivery boy, but there were no other witnesses to prove that. Masako testified that when

she awoke that morning, there were no shoe prints outside the kitchen door. Also, there were no shoe prints near the wall, which surrounded the property and had barbed wire on top of it—making it virtually impossible to walk along it or climb over it.

“Heikichi’s ex-wife Tae and her daughter Tokiko testified for each other. Tae claimed that Tokiko was with her on the 25th. Among the daughters, only Tokiko had an alibi that someone else could attest to, but because it was her mother, her alibi was not absolutely reliable, either.”

“I see. So they were all suspects. Now, what about the mysterious model who never came forward?”

“Well, the police suspected that the woman’s shoe prints could have been left by a model. Umezawa often hired his models through the Fuyo Model Club in Ginza, or else he’d go through one of Yasue’s contacts. But nobody could be found who had worked for Umezawa on the 25th. Moreover, according to Yasue, Umezawa was very excited about having found a model who was exactly right for what he wanted to paint. Apparently, she fit the image of his dream girl, and he was very happy. He was going to dedicate all of his energy to that painting, because it would be the last chance for him to do something so large.”

“Uh-huh,” Kiyoshi grunted. His eyes were closed, and he was slumped on the sofa.

“Are you listening to me?” I asked him. “I’m only going through all this for your benefit! Come on.”

“Of course I’m listening! Please carry on.”

“It seems that the model Umezawa wanted to paint was an Aries, the same sign as his last motif, you’ll remember. Now he

could have used his daughter Tokiko, who was an Aries, but police deduced that Heikichi got someone else because the model would have had to be naked.”

“Fair enough.”

“So the police went to every agency in Tokyo, seeking a model who looked something like Tokiko. The investigation took a month, but they found no one. In the aftermath of the 2-26 Incident, the police became too busy to continue, so the Heikichi murder case was closed. They concluded he must have picked up a girl on the street or in a bar. Perhaps she needed money desperately and was willing to pose naked but wanted to keep it a secret. She could have been a married woman. Anyway, she never came forward.”

“Of course she wouldn’t if she was guilty!” Kiyoshi piped up.

“Huh?”

“Well, let’s say the model killed Heikichi,” he continued. “She could have covered her own shoe prints with a man’s shoes, right? Therefore…”

“That supposition has already been ruled out,” I interrupted. “If she had brought a pair of men’s shoes with her, she must have expected it to snow. But no one knew it was going to snow before it actually started to snow at 2 p.m. that afternoon. And Heikichi’s daughters said that from around 1 p.m. the curtains of the studio were closed, normally a sign that their father had someone with him. The model could have worn Heikichi’s shoes, of course, but the two pairs he kept in his studio were found in their usual place in the vestibule. It would not have been possible for the model to walk back to the studio to return them.”

“If there was a model, that is.”

“Right, if there was a model.”

“The killer could have walked away in a man’s shoes while making the prints of a woman’s shoes.”

I nodded. “Well, yes, that’s possible.”

“But wait… It doesn’t make sense. If a female killer wanted to pretend to be a man, she would have needed only the shoe prints of a man. Why did the person in the man’s shoes need to make those prints of a woman? Good grief!”

“What’s wrong?”

“You’re giving me a headache. You’re like that snowstorm on the 25th—coming and going, starting and stopping. Just give me the facts.”

“I’m sorry. Do you want to take a break?”

“No thanks,” Kiyoshi said, rubbing his temples with both forefingers.

“All right. The facts. Well, there was no evidence left at the scene. Heikichi was a chain-smoker, so there were cigarette butts in the ashtray. And there were fingerprints—some his, some his brother’s, others unidentifiable, maybe from the models he used. There was no sign of any attempt to wipe off fingerprints.”

“Uh-huh.”

“And no murder weapon was found. Nothing in the studio suggested it had been used for the deed.”

“Was there anything that could imply a dying message from Heikichi?” asked Kiyoshi. “For example, there were those paintings of the astrological signs, right? He could have pulled one of them down when he was dying and tried to show what sign the killer was.”

“He probably had no time.”

“Uh-huh. Or he might have been trying to say something by cutting off his beard…”

“They reckoned he died instantly.”

“Instantly?”

“Yes,” I replied. “Well, I’ve told you all I know, so now it’s time for you to start on your deduction!”

“Hmm. All the seven daughters and nieces were killed after that, yes?”

“Yes.”

“So that excludes them from the list of suspects.”

“Be careful not to confuse Heikichi’s murder with the others.”

“Ah, yes. But from the point of view of motive, what do we have so far? Well, there were the family members who wanted—or didn’t want—the apartment building built. Or the daughters might somehow have got wind of Heikichi’s crazy idea for creating Azoth and murdered him before he murdered them. Or some art dealer might have believed that something sensational like this would drive up the price of Heikichi’s paintings. Or… what else?… Kazumi, how much did his paintings sell for after the murder?”

“The large oil zodiac paintings were each worth about the price of a house.”

“Ha! So eleven paintings could have turned into eleven houses?”

“Yes, but all that didn’t happen until more than ten years later. First, the Sino-Japanese War broke out, and then there was Pearl Harbor, and then the Second World War. So there wasn’t much selling of paintings going on in those days. After that,

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders

was published, and it became a bestseller right away. Tae got a lot of money from that; Yoshio,

too, probably. And that’s when the price of the paintings shot up.”

“I see. The story has so much of the occult about it. It must have made quite a sensation.”

“Yes it did. In fact, there was such a big fuss that a book could be written about the fuss alone! One elderly scholar said that Heikichi’s thinking was sickening—it was enough to make even God angry, and his violent death was a display of that anger. Morality was hurled all over the place. Some zealots burst into the Umezawa house. The police had to be called in. People from all walks of life—preachers, psychics, channellers—came from every corner of Japan.”