The Tokyo Zodiac Murders (4 page)

Read The Tokyo Zodiac Murders Online

Authors: Soji Shimada

The line of longitude at 138° 48’ E is full of meaning. Mount Yahiko is located at the northern end of this line. That is where Yahiko Shrine is located. It is the key to the myth. There must be a saint stone. Mount Yahiko is the navel of Japan, the exact centre of the country. No one should ignore this holy place; the future of Japan depends on it. It is the one place I would like to visit before I die. I must, and I will! If I fail to do so because

of my death, I want my children to visit there on my behalf. Mount Yahiko has mystical power.

Four, 6 and 3 are the numbers on the line dissecting the middle of Japan. These three numbers add up to 13, which is the devil’s favourite number. Azoth will be placed in the centre of 13…

“What the hell is all this?” Kiyoshi exclaimed. He closed the book, threw it to me, and lay down on the couch.

“Did you read the whole thing?” I asked.

“Well, Heikichi Umezawa’s story, at least.”

“And what did you think?” I asked.

Kiyoshi, who had been in the doldrums recently, said nothing. After a long pause, he replied, “Well, it was like being forced to read the Yellow Pages!”

“But what about his take on astrology? Was there anything unusual?”

Kiyoshi’s an astrologer, so the question seemed to flatter him. “Well, some parts are based on his own interpretation,” he said. “In astrology, you see, the ascendants characterize the body parts rather than the solar signs, so I would say his interpretation was a bit broad. Other than that, his knowledge was pretty solid. I don’t think he had any crucial misunderstandings.”

“What about his ideas on alchemy?”

“Completely wrong. That kind of thinking was typical among the older generation. It’s like baseball. When it first came to Japan in the 1880s, people thought it was a way to discipline the mind, American-style, but they went too far. They took it so seriously that if they didn’t get a hit, they were ready to commit hara-kiri. Heikichi Umezawa was like that, but I suppose he

knew more than those people who think alchemy is a way to turn lead into gold.”

My name’s Kazumi Ishioka. I’m a huge fan of mysteries; in fact, they’re almost an addiction. If a week goes by without reading a mystery, I suffer withdrawal symptoms. Then I wander around like I’m sleepwalking and wake up in a bookshop, looking for a mystery novel. I’ve read just about every mystery story ever written, including the one about Yamatai, the controversial ancient kingdom, and the one about the bank robber who stole 300 million yen and was never caught. But it’s not an intellectual pursuit; it’s more like me getting my fill of gossip.

But of all the mysteries I’ve read,

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders

was, without a doubt, the most intriguing. The murders actually happened—in 1936, just before the Second World War, at the time of the abortive military uprising on 26th February known as the “2-26 Incident”.

The story was extraordinary—incomprehensible, bizarre and with unbelievable depth. The mystery swept the country like a swarm of locusts. And ever since then—for over forty years—numerous intellectuals and would-be detectives have been trying to figure it out. Of course, to this day, the case remains unsolved.

Documents of the case and the last will and testament left by Heikichi Umezawa were compiled into a book. It came out around the time I was born, and immediately became a bestseller. Part of the bigger picture at the time was that the failure to solve the murders seemed to symbolize the darkness surrounding pre-war Japan.

The most horrible and baffling thing about the case was that six young women were killed exactly as described in Heikichi’s notes. Moreover, they were buried in six different places, each body had a different part missing, and metal elements were buried with them.

The bizarre thing was, Heikichi was killed prior to the deaths of the young women, who were, in fact, his daughters and nieces. Several people’s names were mentioned by him, but they all had alibis. Of course, all the alibis were checked out thoroughly and all the possible suspects were cleared. Heikichi himself seemed to be the only person with a strong motive, but since he was already dead when the murders took place, he was beyond suspicion.

Consequently, the conventional wisdom was that the killer was someone outside the family. The public came up with hundreds of theories, which led only to chaos. Every conceivable motive had already been suggested; things looked like they were at a dead end.

From the late 1970s, a number of books were published that tied the murders to the occult. Most of them were rather crude and shoddily constructed, but they sold very well. So, naturally, more books of the sort were published; it was like a gold rush.

I remember some of the more ridiculous ideas put forward: the Chief of the Metropolitan Police was involved; the Prime Minister had a hand in it; the Nazis wanted the girls for biological experiments; and—the best one in my opinion—cannibals from New Guinea wanted the body parts for eating. These theories were more like a bad joke, but people began to enjoy them. When a gourmet magazine published an article on the fine art of eating human beings, things were clearly out of control. The last crazy idea was that aliens from outer space had done it.

It seemed to me that all these ideas missed two critical points: how could an outsider have read Heikichi’s note, and why would someone want to carry out his plan anyway?

The police focused on the fact that the eldest daughter, Kazue, had Chinese connections and might have been a spy. So there was speculation that a secret military agency might have assassinated the Umezawa girls.

My own far-fetched theory was that someone found Heikichi’s note and then used it as a cover-up for his own crime. The fellow might have been romantically involved with one of the girls—she broke up with him, so he took his revenge. And if he killed all six girls, his motive wouldn’t be obvious. But this theory didn’t quite fit with the fact that, according to investigators, the Umezawa girls were strictly guarded by their mother and didn’t have any boyfriends. Having a date without parental permission was out of the question in the 1930s. And if one of the girls did have a boyfriend that she jilted, surely he could have chosen an easier method of killing her. And again, he wouldn’t have had access to Heikichi’s note.

Nothing made sense. Eventually, I stopped thinking about the bizarre murders.

Kiyoshi Mitarai was usually a very energetic fellow, but in the spring of 1979 he was coming out of a bout of depression. He was not in the best condition to solve such a mystery. Many artists have idiosyncrasies, and Kiyoshi was no exception. He would suddenly become happy with the pleasant taste of toothpaste, or he would suddenly get depressed when his favourite restaurant changed the colour of the tablecloths. Once his mood turned bad, it would last for several days. So he was not an easy man to be around. I’d become used to his

mood swings, but they seemed to be worse than ever. When he went to the kitchen or to the toilet, he moved like a dying elephant. Even when he saw his clients, he looked sick. He was normally bold and cheeky towards me, but right now he wasn’t. To tell the truth, I preferred it that way.

Kiyoshi and I had met the previous year, and since then I had spent much of my free time in his astrology classroom. I would help out when students and clients visited his office. One day, a Mrs Iida came by and said matter-of-factly that her father was involved in the famous Zodiac Murders case. She handed us a piece of evidence, which apparently no one else had seen, and said something to the effect that maybe we could solve the case with it. Kiyoshi was not famous, although he had the respect of his peers. That this woman would entrust such important evidence to him caused him to rise in my estimation. I felt important being associated with him.

It had been a long time since I’d thought about the murders, but it didn’t take me long to recall them. Kiyoshi, on the other hand, didn’t know anything about the case, even though he was an astrologer himself. I had to find

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders

on my bookshelf, wipe off the dust and explain everything to him.

“So, you’re saying that the writer of this note, Heikichi Umezawa, was killed?” Kiyoshi asked, stretching out on the sofa.

“That’s right. You’ll find the details in the second half of the book.”

“I’m tired. This small type is killing my eyes.”

“Oh, come on, stop complaining!”

“Can’t you just give me a rough idea?”

“All right. I suppose you want an outline of the crimes first?”

“Yes.”

“Ready?”

“Just do it…”

“Well, the so-called ‘Tokyo Zodiac Murders’ actually consist of three separate cases. The first was the murder of Heikichi Umezawa; the second was the murder of Kazue Kanemoto, his stepdaughter; and the third was the Azoth multiple murders. Heikichi was found dead in his studio on 26th February 1936. His note, which seemed a very bizarre story on the face of it, was dated five days before his death. It was found in his desk drawer.

“Kazue was killed at her house in Kaminoge, Setagaya Ward, which was quite far from the Umezawas’ house and Heikichi’s studio in Ohara, Meguro Ward. She had been raped, so the deduction was that her killer was male, and probably a burglar. It may have been pure coincidence that Kazue was killed at almost the same time as Umezawa and the others.

“Right after Kazue’s death, the serial murders took place, just as spelt out in Heikichi’s note. They were called ‘serial murders’, but in fact the victims weren’t killed serially, one after the other—they were all killed at more or less the same time. Somehow, the Umezawa family was cursed. By the way, does the date 26th February 1936 mean anything to you?”

Kiyoshi’s answer came quick as a flash: “The 2-26 Incident.”

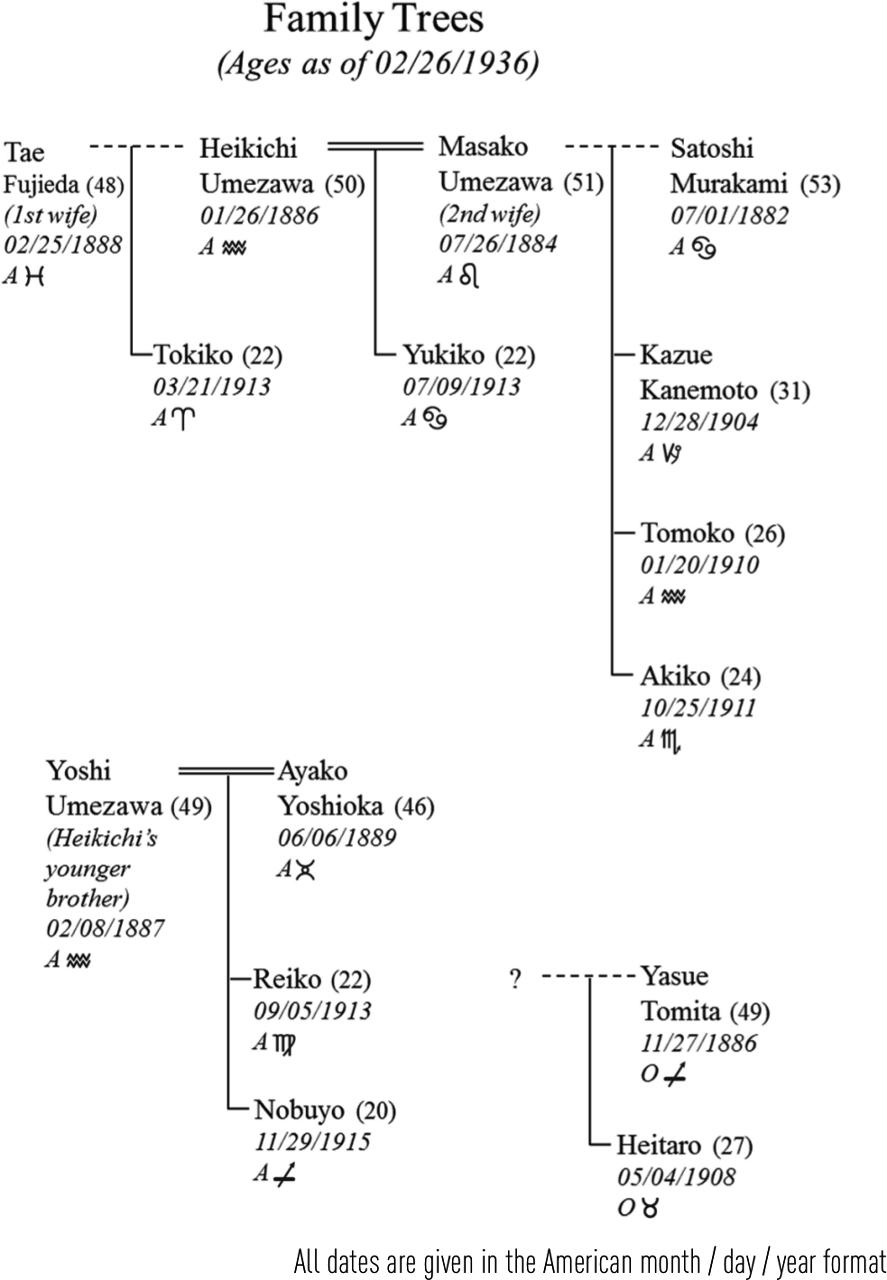

“That’s right,” I said. “I’m very impressed with your knowledge of Japanese history! Heikichi’s death was on the very same day. Oh, that’s what the book said? Well, good. Anyway, let’s take a look at their family tree. Their ages were charted as of that day, 26th February 1936.”

“And their blood types?” Kiyoshi asked.

“Yes, their blood types too. The information in the note was all correct and true. But he didn’t write about Yoshio, his

younger brother, so let me tell you something about him. He was a writer who wrote essays for travel magazines, serialized novels for newspapers, features, etc. When his elder brother was killed, he was up in the north-east in Tohoku, doing research for an article. His alibi checked out, but it would be worth reviewing. Anyway, we’ll get back to Yoshio later.

“Next, Masako, Heikichi’s second wife. Her maiden name was Hirata. She was from a wealthy family in Aizu-wakamatsu. Her first marriage was to one Satoshi Murakami, an executive in an import–export company; it was an arranged marriage. They had three daughters—Kazue, Tomoko and Akiko.”

“I see,” said Kiyoshi. “Now what about Heitaro Tomita?”

“He was twenty-six at the time of the murder. He was unmarried, and was helping at his mother’s gallery, De Médicis. If Heikichi was in fact his biological father, he must have fathered him when he was twenty-two.”

“Could blood type determine if he really was the father?”

“Not in this case. Heitaro and his mother were type O. Heikichi was type A.”

“Now we know Heikichi and Yasue, Heitaro’s mother, broke up in Tokyo and then met up again later. Were they seeing each other in 1936?”

“Most likely,” I replied. “When Heikichi went out to meet someone, it was usually her. It seems he trusted her because they shared the same art interests. Heikichi wasn’t close to Masako or his stepdaughters in the same way.”

“Why did he marry her, then?… Anyway, did Masako and Yasue get along?”

“I don’t think so. They would say hello to each other, but Yasue seldom went to the main house when she visited Heikichi. He spent most of his time in his studio anyway. Now I think about it, Yasue could easily have visited him there without anyone knowing. Heikichi might still have loved Yasue. He married Tae because he was lonely after his mother’s death. Then he was drawn into an affair with Masako—yeah, ‘drawn’ might be the right word to explain his character.”

“So, presumably, Yasue and Masako would never have joined forces…”

“It seems highly doubtful.”

“Did Heikichi see Tae after they divorced?”

“Never. But their daughter, Tokiko, often visited Tae in Hoya. She worried about Tae, who was operating a small cigarette shop by herself.”

“Heikichi was cold-hearted, then?”

“Well, he never visited Tae, and she never visited him.”

“Tae and Masako didn’t get along either, did they?”

“Of course not. Masako took Tae’s husband away from her. Tae must have hated her. That’s a woman’s nature.”

“So, Kazumi, you know all about the psychology of women!”

“What?… No!” I mumbled.

“But if Tokiko was so worried about her mother, why did she stay with the Umezawas? She could have lived with Tae, couldn’t she?”

“I have no idea. I’m not an expert on female psychology!”

“What about Yoshio’s wife, Ayako? Was she close to Masako?”

“They got along well enough.”

“But even though Ayako let her two daughters live with Masako, she chose to stay away herself.”

“There might have been some hostility between them.”

“Back to Yasue’s son, Heitaro. Did he and Heikichi often see each other?”

“I have no idea. The book doesn’t have information going back that far. Heikichi often went to the De Médicis gallery in Ginza. He must have seen Heitaro there from time to time. They might have been friendly.”

“Hmm. Heikichi’s unusual behaviour—which is not so

uncommon among artists—certainly created complicated relationships.”

“Yes, it did,” I said. “A good moral lesson for you, isn’t it?”