The Transformation of the World (56 page)

Read The Transformation of the World Online

Authors: Jrgen Osterhammel Patrick Camiller

City and Industry

Since the nineteenth century witnessed urban development almost everywhere in the world, urbanization was a much more widespread process than industrialization: cities grew and became more dense even where industry was not the driving force. Urbanization follows a logic of its own. It is not a by-product of other processes, such as industrialization, demographic growth, and nation-state building; its relationship with them is variable.

27

A higher level of urbanization at the end of the premodern era was not at all a basis for the success of industrialization. If it had been, northern Italy would have been among the trailblazers of the Industrial Revolution.

28

Industrialization imparted a new quality to the concentration of people in urban settlements. As E. A. Wrigley has shown in a classic essay on London, we should assume that there was a two-way relationship with urbanization. On the eve of the Industrial Revolution, London had grown into a metropolis in which more than a tenth of the population of England lived (in 1750). Its commercial wealth, its purchasing power (especially for food, which in turn stimulated a

rationalization of agriculture), and its concentration of labor and skills (“human capital”) offered the best chances of a multiplier effect for the new production technologies.

29

Complemented and counterbalanced by an urban renaissance in English and Scottish provincial cities, the development of London was part of a more general increase in social efficiency and capacity. Powerhouses of the Industrial Revolution such as Manchester, Birmingham, and Liverpool became huge cities, but in the second half of the nineteenth century the fastest developers were ones with a large service sector and an exceptional ability to process information in relationships of direct contact.

30

In continental Europe and other parts of the world, and also in Britain itself, rapid urbanization occurred where local industry

could not

have been

the ultimate cause.

Many examples show that nineteenth-century cities grew in the absence of a noteworthy industrial base. Brighton, on the south coast of England, was one of the fastest-growing cities in the country, but it had no industry. The dynamic of Budapest was due less to industry than to the interplay of agrarian modernization and key functions in trade and finance.

31

Also cities in the Tsarist Empire such as Saint Petersburg and Riga owed their constant population growth to commercial expansion, which was bound up with an extensive and productive crafts sector; industry played a subordinate role there.

32

In a particularly dynamic field of economic development, cities might let opportunities slip: Saint Louis, until the mid-1840s, grew with breathtaking speed into the leading city of the Mississippi Valley and the center of the whole American West. But it passed up the chance to acquire an industrial base. It soon faced economic collapse and had to surrender its lead to Chicago, having allowed the window of opportunity to close.

33

A trip around the downtowns of London, Paris, or Vienna reveals that they were never industrial; indeed, their cityscapes testify to a struggle in the past to prevent industry from destroying their distinctive culture. The emblematic metropolises of the nineteenth century created their enduring appearance more by fending off industrialization than by surrendering to its consequences.

34

And the twentieth-century growth of giant cities without an industrial base (Lagos, Bangkok, Mexico City, etc.) should make us further aware that there is only a loose association between urbanization and industrialization. Urbanization is a truly global process, industrialization a sporadic and uneven formation of growth centers.

Top Cities

Only if urbanization is considered outside the time frame of the nineteenth century and a narrow association with “modernity” can the place of that century in the

longue durée

of urban development be properly determined.

35

This also calls into question Europe's claim to a monopoly on urbanization. The big city was no more invented in Europe than the city in general was. During the longest part of recorded history, the world's most populous cities were in Asia and North Africa. Babylon had probably passed the 300,000 population mark by 1700 BC.

Rome under the emperors had a larger population than even the leading Chinese cities at that time, but it was a unique case. It embodied itself, not “Europe.” In the second century AD more than a million people lived in Romeâa figure not reached by Beijing until the late eighteenth century or by London until shortly after 1800.

36

Imperial Rome was a one-off in the history of human settlement. It did not stand at the top of a finely tapering pyramid of cities; it hovered, as it were, above a world of scattered settlements. Only Byzantium at its height (before the catastrophe of the First Crusade, in 1204), which also did not rest upon a graded hierarchy of cities, came close to the dimensions of such a world city.

In general, population figures for non-Western citiesâeven more than for European or American onesârely on often insecure premises until well into the nineteenth century. In 1899 Adna Ferrin Weber, the father of comparative urban statistics, laconically observed that the Ottoman Empire was full of cities but that only the larger ones were “known to the statisticians, and these imperfectly.”

37

The following data should therefore not be regarded as anything more than informed guesses. The larger the city, the more likely it was to have made travelers and commentators feel that they had to judge its exact size. At least this allows us to gauge the order of magnitude of the world's largest cities at selected points in time.

In 1300, Paris was the only European city among the top ten in the world, taking sixth place after Hangzhou, Beijing, Cairo, Canton (Guangzhou), and Nanjing, but ahead of Fez, Kamakura (in Japan), Suzhou, and Xi'an.

38

Six of these cities were in China, Marco Polo's reports about which were beginning to reach Europe. By 1700 the picture had changed. As a result of development in the early modern Muslim empires, Istanbul was then number one, Isfahan three, Delhi seven, and Ahmadabad, also in the Indian Mogul Empire, number eight. Paris (5) had slipped a little behind London (4) and would never catch up to it again; they were the only two European cities on the list. Beijing remained the second-largest city in the world. The others in the top tenâEdo, Osaka, and Kyotoâwere in Japan, which under the Pax Tokugawa had just bid farewell to a century of stormy urban development.

39

By 1800 the picture had changed again, but only slightly:

40

1. Beijing | 1,100,000 |

2. London | 950,000 |

3. Canton | 800,000 |

4. Istanbul | 570,000 |

5. Paris | 550,000 |

6. Hangzhou | 500,000 |

7. Edo (Tokyo) | 492,000 |

8. Naples | 430,000 |

9. Suzhou | 392,000 |

10. Osaka | 380,000 |

Six of these cities were in Asiaâor seven, if we include Istanbul. After London, Paris, and Naples, the next European cities to figure are Moscow (fifteenth, with 238,000 inhabitants), Lisbon (sixteenth, with approximately the same number) and Vienna (seventeenth, 231,000). Of the twenty-five largest cities in the world in 1800âif we follow the estimates of Chandler and Fox, which are supported by other sources, though inevitably not based on a uniform concept of the cityâonly six were in Western Christendom; Berlin had a population of 172,000, which made it roughly the same size as Bombay (Mumbai) or Benares (Varanasi). The most populous city in the Americas was Mexico City (128,000), followed by Rio de Janeiro (100,000), the key center of Portuguese America. Even in 1800 North America was lagging in this respect: its largest city was still Philadelphia (69,000), the first capital of the United States. But New York was preparing to take the lead. Thanks to an extraordinary surge in immigration and an economic boom, it was already the main Atlantic port and in the new century would also become the largest city in the United States.

41

Australia, soon to join North America as an area of explosive demographic growth, had scarcely any urban history in 1800. Its entire population of European origin would easily have fit into a small German princely residence.

42

These numerical impressions would suggest that in 1800, China, India, and Japan were still the dominant urban cultures in the world. It is true that what was meant by “city” varied enormously. European visitors found the walled cities to which they were accustomed most often in China, but even there not all throughout the country; and travel reports repeatedly speak of Asia's shapeless, “nonurban” cities. Sometimes the distinction between city and country seemed to lose all of its sharpness. The island of Java, for example, very densely populated in the nineteenth century, was not centralized in a few large cities, nor did it have the isolated, largely autarkic villages that people liked to imagine in Asia: it was one large intermediate area of settlement between city and country, essentially neither the one nor the other.

43

Nevertheless,

every

city was a sphere of dense communication and a consumer of surpluses produced in the country; it was in some way a nodal point of trade or migration. Each had to contend with supply and public order problems that were different from those in “the countryside.” Asia's big cities somehow managed to solve these problems: otherwise they would not have existed. Even the most blinkered traveler could tell when he was in a city; the grammar of urban life was comprehensible across cultural frontiers.

Urban Populations: East Asia and Europe

Urbanization, understood as a measurable state of society, is a relative and obviously artificial indicator concocted by nineteenth-century statisticians. It implies that the growth of particular cities is related to their surroundings, the key yardstick being their share of the total population of a country. This share is not necessarily highest in regions with the largest cities. It is therefore illuminating to compare Europe with the countries of East Asia where the largest urban concentrations were found in the early modern period. In 1600, Europe had already reached a slightly higher level of urbanization than China, where the urban share of the proportion had remained roughly the same for a thousand years. But

on average

Chinese cities were larger than European ones. Two regionsâone on the Lower Yangtze (Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Suzhou, etc.), the other in the Southeast, around and inland from the port city of Cantonâcontinually amazed early modern European travelers with the density of their population and the size of their cities. In 1820 there were 310 cities in China with more than 10,000 inhabitants; in Europe, outside Russia, there had been 364 at the beginning of the century. The average was 48,000 inhabitants in China, and 34,000 in Europe.

44

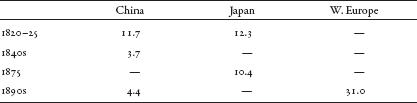

Table 6: Percentage of Population in Centers with More than 10,000 Inhabitants: 1820â1900

Sources:

China and Japan: Gilbert Rozman, “East Asian Urbanization in the Nineteenth Century: Comparisons with Europe,” in: Woude et al.,

Urbanization in History

, p. 65 (Tab. 4.2a, 4.2b); Western Europe: Maddison,

World Economy

, p. 40 (Tab. 1-8c).

Table 6

gives comparative population percentages for selected times in the nineteenth century. It indicates both Japan's constant middle position between China and Western Europe and the extraordinary speed of city formation in Europe after the first quarter of the century. Shortly before the West opened up the two largest East Asian countries, the share of cities in Japan's total population was more than three times greater than in China's. Is this, however, a methodologically legitimate comparison? Was Japan alreadyâby the criterion of urbanizationâmore “modern” than China? The gap narrows if we break down the averages: that is, if we compare Japan not with the immense territory of China as a whole but with its economically most developed macroregion, the Lower Yangtze. In that case the demographic figures are roughly similar. In the Lower Yangtze in the 1840s, city dwellers made up 5.8 percent of the total population. By 1890 this rose to 8.3 percent, not far short of Japan's 10.1 percent in its early industrialization period.

45

This means that in these two densely populated regions, the absolute numbers were as follows: 3.7 million Japanese lived in cities with a population of 10,000 or more in 1825, but only 3.3 million did so in 1875; while the figures in China were 15.1 million at the time of the

Opium War and 16.9 million in the 1890s.

46

For Europe we have the estimates of Paul Bairoch and his collaborators, who define any settlement with more than 5,000 inhabitants as a city; this gives 24.4 million city dwellers in continental Europe in 1830, and 76.1 million in 1890.

47

The orders of magnitude can here only be approximate, but in 1830 it was not the case that an urban Europe faced a rural East Asia, whereas by 1890 the the gap between them had widened dramatically.