The Triumph of Seeds (25 page)

Read The Triumph of Seeds Online

Authors: Thor Hanson

Tags: #Nature, #Plants, #General, #Gardening, #Reference, #Natural Resources

F

IGURE

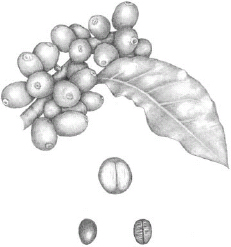

10.2. Coffee (

Coffea

spp.). Beloved for their stimulating caffeine and complex flavor, the seeds of these small African trees have become the world’s most traded commodity. The berry-like fruits pictured at the top and in cross section each contain two seeds that swell and darken when roasted (below). I

LLUSTRATION

© 2014

BY

S

UZANNE

O

LIVE

.

“I’ll put you right over here,” said co-owner Chelsey Walker-Watson, greeting me at the door with a smile and a handshake. She sat me at the counter between two people who were also holding notepads, and for a terrible moment I thought that they, too, must be writing books about seeds. But then Chelsey introduced them as new employees and explained that I would be sitting in on a training session. So for the next three hours I remained there at the counter—brewing coffee, drinking coffee, talking coffee, and learning what it takes to be a barista at the hippest coffeehouse in the country.

“Basically, I got a job at Peet’s because my boyfriend wanted free coffee,” Chelsey admitted, when I asked how she got started in the business. Petite, with hair the same dark shade as the frames of her

glasses, she had a self-deprecating style that belied the obvious success of her career. I didn’t ask whether the boyfriend had lasted, but the coffee certainly had. She’d spent a decade rising through the ranks at Peet’s—the third-largest specialty chain in the country—before leaving to start Slate. And now, within a year of opening, the shop was already winning national awards. The Slate approach gets back to basics, focusing on coffee beans as the seeds of a plant, and recognizing that differences in growing conditions—soil, elevation, rainfall—can have a distinct impact on how those beans come out. They can vary not only in size, color, and density, but also in their chemistry, since the pests they face in a place like Vietnam will be very different from those found in Ethiopia, Colombia, or Martinique. Where most coffeehouses strive for uniformity from cup to cup, the Slate team tinkers with every roast and brew to highlight any potential difference in flavor.

“It’s like making toast,” explained head barista Brandon Paul Weaver. “White bread and whole wheat bread are very different, but if you burn them they taste exactly same.” The trick lies in roasting the beans just enough to make toast, but not so much that they lose their uniqueness. “They can’t be too raw, either,” he qualified, making a face. “Raw beans just taste like grass.”

After all the buildup, I wasn’t sure what to expect when Brandon handed me the first small cup of the day. But one sip confirmed that Slate’s coffee wasn’t like anything I brewed at home. It tasted like some kind of intense herbal infusion—coffee, but with strong hints of citrus and blueberry. “What do you think?” Brandon asked eagerly, drinking from his own small cup. “Are you getting the jasmine notes?”

Tall and lanky, Brandon wore his dark curls long, with a gravity-defying straw hat perched haphazardly on the back of his head. He took over the training session as Chelsey got busy with customers, speaking in rapid bursts about grind texture, water temperature, and saturation point. Brandon brewed each cup separately, using hot plates, scales, and large beakers like something out of a chemistry

lab. The recipe that won him top barista honors at the Northwest Brewers Cup competition was recently posted online: “19.3 grams coffee (from the Limu region of Yrgacheffe, Ethiopia); Moderate-course grind on a Baratza Virtuoso grinder; 300 grams of 205-degree water; Kalita filters in a Clever Dripper; 3 minute, 15 second brew time.”

This kind of attention to detail may seem obsessive, but Brandon, Chelsey, and everyone at Slate want coffee to take its place beside fine wine as a beverage of nuance. If they’re successful, people will start appreciating coffee beans with the same focus given to wine grapes, recognizing varieties, appellations, and the rewards of a good harvest. This approach to coffee appreciation is new, and it seems to be catching on with serious connoisseurs. In contrast, Slate’s goal for their coffeehouse is very traditional: they want it to be a place for conversation.

“I’m interested in what the coffee can facilitate,” Brandon said, and talked about watching great interactions develop among total strangers seated at the counter. As if to demonstrate his point, our little training session soon drew a small crowd of onlookers, serious coffee enthusiasts who wanted to try Slate’s methods at home. Or, for the fellow standing behind me, on the job. He was a barista at Toast, another Ballard coffeehouse. “I just got off work and thought I’d stop in for a cup on my way home,” he said, with no trace of irony. The crowd ranged from skinny teenagers to a retired couple, and even a tourist from Georgia who’d read about Slate on a coffee blog. At one point, people were so intent on watching Brandon pour that no one noticed the record player was skipping, endlessly repeating a fast Benny Goodman lick on the clarinet. It was some kind of ascending jazz arpeggio, the perfect musical accompaniment to coffee—

up, up, up

!

After three hours of steady coffee tasting, my brain felt like it was starting to skip, too. I could picture a swarm of caffeine molecules up there, thumbing their noses at the adenosine. Driving away, it occurred to me that in all of our conversation, one topic hadn’t come

up: decaf. To aficionados like the crew at Slate, taking the caffeine out of coffee defeats the purpose and spoils the taste, but decaf still makes up 12 percent of the world market. The process usually involves solvents or complex steam and water baths, but there is a holy grail out there for decaf drinkers. Among the hundred or so species of wild coffee, a handful in East Africa and Madagascar lack caffeine naturally. Their ancestors branched from the coffee family tree sometime before caffeine evolved, and they’ve never developed the knack. Domesticating one of those species holds the promise of a full-flavored decaffeinated coffee straight from the bean, with no processing required. In today’s market, that translates to a $4 billion idea, and plenty of plant breeders have tried it. But just because a coffee tree lacks caffeine doesn’t mean it lacks pests. The decaf species face the same kinds of attackers as any other coffee, and they’ve developed their own suite of chemical defenses in lieu of caffeine. Unfortunately, for every variety studied to date, that chemical cocktail makes the beans disgustingly bitter. The quest for a natural decaf continues, but so far it has yet to produce a drinkable cup.

Late that night, still fidgeting and staring at the ceiling, I found myself wishing the decaf researchers Godspeed. I slept eventually, but it was a good reminder that plants don’t put alkaloids like caffeine into their seeds for our pleasure. They’re meant to be toxic, as indeed they are to a good many insects and fungi. It’s even possible for a person to die from caffeine overdose, though one study suggests it would take 150 cups of coffee, drunk all at once, to do the job. Poisoners and assassins know that there are far more lethal options available, and, not surprisingly, many of them also come from seeds. In fact, the most notorious assassination of the Cold War revolved around three things: a bridge, an umbrella, and a bean.

If you drink much from a bottle marked “poison,” it is almost certain to disagree with you, sooner or later

.

—Lewis Carroll,

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

(1865)

I

n novels, thick fog always envelops the city of London just when something dramatic is about to happen. It hides the robberies and the kidnapping in

Oliver Twist

. It shrouds the arrival of Dracula when he comes for Mina Harker, and Sherlock Holmes watches it swirl down the street before the fateful events in

The Sign of Four

. But on September 7, 1978, light morning showers had given way to sunshine by the time Georgi Markov parked his car and began walking toward the Waterloo Bridge. Had it been foggy, Markov might have left his windbreaker in the closet and donned an overcoat, or at least a pair of heavier trousers. Either one could have saved his life.

At home in Bulgaria, Markov’s novels and plays had made him a famous literary star, someone who mingled with the social and political elite. He’d even gone on hunting trips with the president. Since defecting to the West, that insider knowledge had helped him craft accurate and scathing commentaries on repression behind the Iron Curtain. He hosted a weekly show on Radio Free Europe and also

worked at the BBC, where he was heading on that fateful afternoon. Markov knew that speaking out put him at risk, and he’d even received the occasional death threat. But he was a relatively minor figure—no one expected him to be the target of a plot, let alone one that would become the Cold War’s most infamous assassination. And no one could have predicted the murder weapon, something so preposterous even his widow found it hard to believe.

Walking past a bus stop on the south side of the bridge, Markov felt a sudden jab in his right thigh and turned to see a man bending over to pick up an umbrella. The stranger mumbled an apology, hailed a nearby cab, and disappeared. When he reached his office, Markov noticed a spot of blood and a tiny wound on his leg. He mentioned it to a colleague, but then dismissed the incident from his mind. Late that night, however, his wife found him stricken with a sudden and violent fever. He told her about the stranger at the bus stop, and they began to wonder—could he possibly have been stabbed by a poison umbrella? What had really happened was even more bizarre.

“The umbrella gun was invented by the KGB equivalent of Q’s lab,” Mark Stout told me, alluding to the fictional workshop for spy gadgetry made famous in James Bond movies. But while exploding toothpaste and flame-throwing bagpipes play well in Hollywood, exotic weapons are a rarity in real-life espionage. “It’s almost always low-tech,” Stout went on. “Somebody shoots somebody, or a bomb goes off. At the time, the umbrella gun, and the tiny pellets it fired, were a substantial feat of engineering.”

I called Mark Stout about the Markov case because for three years he had held the position of chief historian at the International Spy Museum. That job title must have looked great on a business card, but it also gave him access to a working copy of the umbrella gun, built by a veteran of the same KGB lab that created the original. The replica features prominently in a section of the museum called “School for Spies,” where it’s displayed alongside another KGB invention, the single-shot lipstick pistol. By the time I spoke

with him, Stout had moved on to a more traditional academic post, but he still showed an obvious enthusiasm for the world of secret agents. “The umbrella used compressed air, exactly like a BB gun,” he explained eagerly. I could hear the squeak of his desk chair over the phone, and pictured him rolling around his office, pausing to lean back in thought. “But it was designed for extremely short range, an inch or two maximum. In Markov’s case, they literally pressed the tip against his leg before firing.”

For pathologists working in 1978, however, there were no spy museums or historians to turn to. Their patient soon died in a London hospital from what appeared to be acute blood poisoning, but they had no logical explanation for his symptoms. The autopsy did note an inflamed pinprick in his thigh, but it looked like an insect sting, not a stab wound. And the mysterious pellet lodged inside was so minute that technicians dismissed it as a blemish on the X-ray film. The investigation might have stopped there if another Bulgarian dissident hadn’t come forward with a similar story. He’d been attacked near the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, but had recovered after a short illness. This time, doctors paid attention to his account of a painful jab, and they soon recovered a tiny platinum sphere from the small of his back. Because he’d been wearing a heavy sweater, the pellet hadn’t penetrated beyond a layer of connective tissue surrounding the muscle, and most of its poison had failed to disperse. London’s coroner immediately reexamined Markov’s body, recovered an identical pellet from the wound in his leg, and came to a famously circumspect conclusion of foul play: “I cannot see any likelihood of this being an accident.”