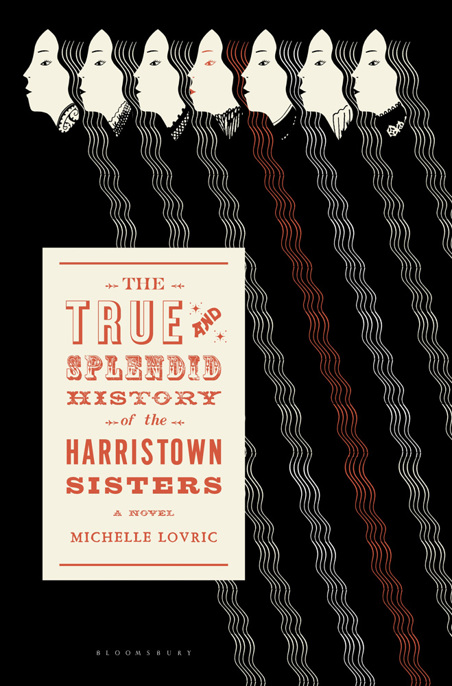

The True and Splendid History of the Harristown Sisters

Read The True and Splendid History of the Harristown Sisters Online

Authors: Michelle Lovric

to my caravan of nymphs

Contents

October 1865

Joe the seaweed boy jolted us on his cart through the rain towards Kilcullen Town. High sodden hedges and our damp bonnets foreclosed on the sky. The rich mud sluiced through our wheels, uttering long vulgar kisses. Our feet pressed down on rags of dead seaweed, perfuming the air with sourness and a faint memory of salt.

Enda held Oona’s hand and mine; Berenice clutched Ida’s and Pertilly’s.

Darcy held no one’s hand, of course.

The slow crows wheeled above us, sonorous in their derision for the seven Swiney sisters in their threadbare finery. Most of all they lifted their beaks against me, Manticory, for they had witnessed my disgrace on Harristown Bridge.

‘Would you look at that!’ Oona pointed at a sheet impaled on a pair of rakes, her finger blurring with fear.

In letters draggling in the rain, it announced:

The Swiney Godivas

Seven Singing Sisters with Seven Sweet Throats

First ever show tonight

Old Kilcullen brooded like a beetle around the next hedge and in the heart of its black streets lurked Ladysmildew Hall, where we were to be sacrificed.

We had a bare hour’s rehearsal before tea.

The hall’s wooden floor rose up to trip our tapping heels in a way the dirt of our barn floor never had. And plump Pertilly landing from a leap was a thing you could hear quite loudly in the next county, according to Darcy.

Outside, the rain beat down like a blacksmith.

Inside, the gas lamps commenced to whisper.

We broke for bread-and-dripping with tea, consumed in the silence of bare terror. Pertilly dressed our hair one last time, cleverly coiling and balancing it on the strength of two stout pins.

As the second hand of the clock strutted round to five minutes before six, Darcy herded us back to the stage. Peering out through the mothy curtain, Oona and Pertilly reported on an audience of fifty sniffing matrons and two dozen sorry-looking youths who shuffled in with their hands in the pockets from which they had just extracted six hard-won pennies for the pleasure we had promised to give them.

‘Nobodies, noodles.’ Darcy paced up and down behind the curtain. ‘And a good thing, too. No one to bother with if you bosthoons make fools of yourselves, as you undoubtedly shall.’

She’d neglected to whisper. Mrs Godlin from the Kilcullen dispensary tutted loudly from the front row. Pertilly waggled a hand through the curtain, greeting Mrs Godlin in our local fashion, ‘To you.’

Mrs Godlin just had time to nod, ‘From you,’ before Darcy had her fingers around Pertilly’s throat and was dragging her away for punishing.

Oona whispered that the seaweed boy Joe had settled himself into the very front row, like royalty.

‘I shall die of fright if you make me go out there,’ Oona told Darcy, over Pertilly’s sobs. ‘How shall I bear it?’

Darcy was not your woman for ‘how’. She was more your woman for ‘when’.

‘Don’t be talking blethers,’ she growled. ‘You’ll be lying in your straw bed tonight dying of nothing to eat if you don’t do this now.’

‘Or maybe sooner, if you cross her,’ I said.

‘You are the worst thing on two feet in Ireland, Manticory.’ Darcy stamped hard on my left one. Under her breath, she muttered, ‘You and your goings-on on Harristown Bridge. Is it worried you are, that

he

’s down there in the audience?’

My heart dropped into my belly that she’d said those things aloud.

The curtains were already creaking apart. We stood still for a moment in a state of fossilising fear. Then Darcy swept to the centre of the stage and began to sing. The hall filled up like a milk pail with the goodness of lovely noise, for the throat of a nightingale was in Darcy’s neck, even if a viper’s tongue was in her mouth.

From the wings, I ran my eyes over the audience. He was not there, himself, the man.

Only Darcy knew of him. The oldest of us she was, nineteen at that time, Darcy of the Ethiopian-black hair, coiling and crinkling like the sea in a sunless cave. With her hair came a serpentine muscularity of body and will. Darcy’s rages could encircle and choke the life’s will out of you.

Darcy retired from the stage, applause clattering behind her.

Next were our twins, lively Berenice and my most darling Enda, who had matching shades of soft brown – Madonna-coloured – hair. They sang a tense duet, each gesture in perfect harmony, as if they did not hate one another worse than a devil and an angel.

Could I tell Enda what had happened to me on Harristown Bridge? So soft, so tender, Enda would cry a well for me, but could she help me?

Could I tell Berenice? I could not, brave and bold as she was. She was my enemy, because she was Enda’s.

Now chestnut-tressed Pertilly bumbled out in front of the audience, perfectly sure, as ever, of disappointing. Poor Pertilly was not pretty at all. Not quite thirteen, she did not have even that freshness of youth we in Harristown called ‘pig-beauty’. Her nose loomed too large and her fleshy upper lip hung unbecomingly over the lower one. Worst of all, her eyebrows drooped the wrong way like the dispirited tails of two dead mice. She laboured away at her stanzas.

Could I tell Pertilly? No, Pertilly would carry it hard. She would sag with the sorryness of it. The secret would seep out of her, somehow. And Darcy would pummel her for that.

Pertilly’s song was mercifully done away with. Then Oona stepped up on the stage to refresh the desire of the audience for Swiney sisters. Oona, fairy-featured and amiable, had blonde hair, thick and soft as mounds of fresh butter churned in a moonlit barn. Like Oonagh, Queen of the Fairies, she had a fey, coaxing way about her. But even at eleven she spoke in a strong bass voice and could pass for a man in the dark. When she opened her mouth on her ballad of first love, the audience sighed with shock and delight.

Could I tell Oona? I could not. The nerves on her were so delicate and eleven was too young to take on my burden.

Next on stage was Ida, christened ‘Idolatry’, the dark-brown baby of the Swiney sisters, with dark-brown moods to match, and an irrepressible tendency to pluck the hairs from her head and wind them round her wrists and ankles. She lisped her lines about a beloved dead kitten with a furrowed brow and wandered uncertainly from the stage in the wrong direction.

How could I tell Ida? She hadn’t ten years on her yet. I prayed she would not even understand the goings-on upon Harristown Bridge or in the copse beside it.

Although I am the middle sister, Darcy had left me to last.

Myself, I am called Manticory, tiger girl, on account of the red hair that is fierce upon my head. Darcy wanted me last on the stage, to give me the longest agony of anticipation, as a punishment, and because of my hair, the redness of it, which was enough to have got me into the heinous kind of trouble that I could not tell my sisters about.

Aware only of the pins and needles in my hands and the shame that clothed me tighter than my bodice, I gave them a song of a red-haired shepherdess. Darcy’s drilling served me well, galvanising my legs and arms, drawing the songs out of me, as if I were still in the tumbledown barn. I danced. I bowed. I walked off the stage in a wind-up kind of fashion and into Enda’s arms.

‘You’re stiff as a corpse,’ she whispered, kissing me. ‘Calm yourself. It’s a done thing now. Nearly.’

For we had still the ensemble piece to perform. It had nothing to do with music, or dancing, or young Irish girls singing their Famined hearts out.

It was the thing upon which Darcy pinned the whole show and our fortunes.

We filed on stage, carrying seven wooden chairs. We set ourselves upon them with our backs turned to the audience.

Simultaneously, we raised our white arms, extracted the crucial pins from our chignons and lifted our loosened hair high above our heads.

And that was when the Swiney Godivas of Harristown slowly liquefied the fat of every heart in Ladysmildew Hall.

Slow, it was, because hair bunched by hand and then let to drop does not do so in a single moment. It falls in sighing increments, a first flump, a gradual unwinding, to twists of blunt ends slithering against the neck, the hanks still smooth and unified from their confinement. Finally, each separate hair finds its appointed resting place.

The hair of the seven Swiney sisters took a long sweet time in falling, not just because of the great weight of it, but because of its unreasonable length. You see, between us we’d already grown forty feet of the stuff, enough to swaddle twenty babies or wind ten grown corpses; more than enough to cover our Swiney bodies and to caress our heels.

Our hair fell with a palpable breeze that touched the faces of those in the front two rows, turning them bloodless or coralline.

And still it kept slithering and sidling and tralloping down to the dust of the wooden floor.

Just like the thin geese, the slow crows and the kittens who had witnessed all our rehearsals, the matrons and boys watched us in breathtook silence, their heads as stiff on their necks as the stump of the round tower at Yellow Bog.

When all the uncoiling, rustling and falling was done, we presented a shimmering waterfall of hair, black, brown, red and blonde, a quantity of hair to terrify you and to knock your beating heart across you, and make you wish you’d been born with two of them just to take in all that hair without fear of a rupture.

‘Is that the kind of thing you’re after wanting?’ Darcy turned and asked our audience.

The boys threw their caps in the air and the women shrieked.