The Undertaking (14 page)

Authors: Thomas Lynch

About the only thing I knew for sure about my future was that I wanted to spend a good portion of it in the embrace

of Johanna Berti, or someone like her. She had recently disabused me of years of blissless ignorance the nuns and Christian Brothers had labored to maintain. For these, the only good body was a dead body: Christ’s. St. Stephen’s, St. Sebastian, the poor bastard, St. Dorothy, Virgin and Martyr, patroness of gardeners. In parochial school of the fifties and sixties, love and death were inexorably connected.

Passion meant a slow death for a good cause. Our schoolrooms and psyches were galleries of crucifixions, martyrdoms, agonies in the garden, ecstasies of

unspecified origins, all for the sake of love. Johanna, herself a good Catholic and Italian who bore more than a passing resemblance to St. Catherine de Ricci, the correspondent of St. Philip Neri, fixed all of that in the ordinary way—by extending

the available welcomes of one body to another. My future seemed abundant and shapeless.

I

was living in my father’s funeral home at the time. Not the one I own and operate now, but an earlier version. I took death calls at night and went on removals. One night a woman called to say her son had “taken his own life” and was now at the county medical examiner’s where they would be doing an autopsy

in the morning and would we go then and pick him up. When I got him back to the funeral home and unwrapped him, I was amazed at the carnage. The T-shaped incision on his chest was no surprise—the standard thoracic autopsy. But unwrapping his head from the plastic bag the morgue-men had wrapped it in, I found a face unimaginably reconfigured. There were entire parts of his cranium simply missing.

He’d gotten a little liquored up and gone to the home of his ex-girlfriend. Rumor was she had broken up with him a week or two earlier and he had moped around the edges of her life in a way we would call “stalking” nowadays. He drank too much. He went to her house where he pleaded with her to take him back. Of course, she wouldn’t, couldn’t, wanted to be “just friends,” etc …, and so he broke

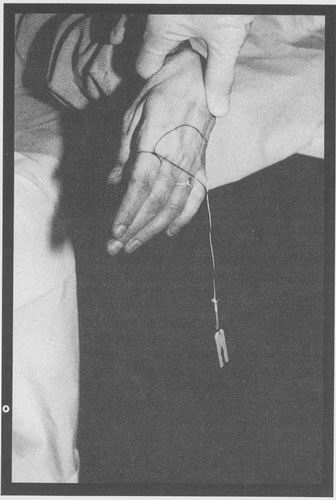

in, ran up to her parents’ bedroom, where he took the deer rifle from her father’s closet, lay on the bed with the muzzle in his mouth, and pulled the trigger with his big toe. It was, according to the ex-girlfriend, “a remarkable gesture.”

As I considered the gesture on the table before me, it struck me, he looked ridiculous. His face had been split in two by the force of the blast, just above

the bridge of his nose. He looked like a melon dropped from the cart, a pumpkin vandalized by neighbor boys. The back of his head simply wasn’t. Here was a young man who had killed himself, remarkably, to deliver a

message to a woman he wanted to remember him. No doubt she does. I certainly do. But the message itself seemed inconsequential, purposefully vague. Did he want to be dead forever or

only absent from the pain? “I wanted to die” is all it seemed to say clearly. “Oh” is what the rest of us say.

But fixed in my remembrance is the way one eye looked eastward and one eye west; a perspective accomplished by the division of his face by force of arms. It seemed that this vantage would give a balanced vision: an eye on the future and an eye on the past. A circumspection by which where

he’d been and where he was going melded into balance. But in the case before me, it was clear, vision was impossible. He was dead. So a sub-theory of the first I began to develop was that balance and vision could not be forced. Violence was not the way to vision. Guns wouldn’t work for this. It had to be grown into, inhabited the way the wood does trees. The fellow before me on the porcelain

table had achieved perspective at the expense of vision, vantage at the expense of life itself. He looked ridiculous and terribly damaged. And ever since, though I have felt helpless, and hopeless, and murderous, and grieved, I have never had, that I can remember, a suicidal moment in my life.

Walking upright between the past and future, a tightrope walk across our times, became, for me, a way

of living: trying to maintain a balance between the competing gravities of birth and death, hope and regret, sex and mortality, love and grief, all those opposites or nearly opposites that become, after a while, the rocks and hard places, synonymous forces between which we navigate, like salmon balanced in the current, damned some times if we do or don’t.

I

t happened for me one night some years

ago. Is it needless to say we had just made love? She lay smoking a cigarette beside me. I was propped on my elbows looking out of the window. The night was Tuesday and moonlit, the end of October, All

Hallows’ Eve. We had buried my mother that morning. We’d stood in the gray midmorning at Holy Sepulchre watching the casket go into its vault, a company of the brokenhearted at the death of a good

woman, dead of cancer, her body buried under the din of priests and leaf fall and the sad drone of pipers. It had been a long day. I was trying to remember my mother’s voice. The tumor had taken it from her in doses. I was beginning to panic because I’d never hear her voice again, the soft contralto, full of wisdom and the acoustics of safety.

And there, for a moment, I could see it all that

night. Between the dead body of the woman who had given me life and the lithe body of the woman who made me feel alive, I had a glimpse of my history back to my birth and a glimpse of the future that would end in my death.

And the life on either side of that moment was nothing but heartache and affection, romance and hurt, laughter and weeping, wakes and leavetakings, lovemaking and joys—the

horizontal mysteries among a landscape that looked like Kansas. I was overwhelmed with grief and desire. Grief for the mother that birthed me, desire for the woman beside me unto death. In such a moment the past loses its pull, the future its fear.

I was forty-one that October. And there are times, still, I’m tempted to reckon the math of it, or the geography, or the algebra or biology—to coax

life’s facts into some paradigm that suits, to say it’s just like this or it’s just like that. But since that night, afloat between the known affections of women who’ve loved me, I have lost my taste for numbers and easy models. Life’s sciences have more to teach me still.

Revision and prediction seem like wastes of time. As much as I’d like to have a handle on the past and future, the moment

I live in is the one I have. Here is how the moment instructs me: clouds float in front of the moon’s face, lights flicker in the carved heads of pumpkins, leaves rise in the wind at random, saints go nameless, love comforts, souls sing beyond the reach of bodies.

Instead of having “answers” on a math test, they should just call them “impressions,” and if you got a different “impression,” so what, can’t we all be brothers?

—J

ACK

H

ANDY

,

D

EEP

T

HOUGHTS

U

ncle Eddie needed an 800 number. His sideline in the suicide clean-up trade was going gangbusters. Business was booming. They were dropping like flies. He needed a separate line, a logo, a slogan,

and magnetic business cards. I was touched that he would come to me, his much elder brother, for free advice.

“Whadaya think about 1-800-SUICIDE? Too morbid? Too direct?”

“Well, Ed …”

“Or 1-800-TRIPLE S? You know. For

Specialized Sanitation Services

?”

In his heart of hearts he had hopes that Triple S—for

Specialized Sanitation Services

—would become as widely recognized as Triple A had for

the Automobile Association of America, or WWW for the World Wide Web, or Triple X for a type of film, the watching of which, Uncle Eddie always said, aroused his pride in First Amendment Rights.

Perhaps his services were a little

too

specialized—known only to local and state law enforcement agencies and county medical examiners and funeral homes; only needed by the families and landlords of the

messy dead. Indoor suicides, homicides, household accidents, or natural deaths undetected in a timely fashion—these were the exceptional cases that often required the specialized sanitation services that Uncle Eddie and his staff at Triple S—his wife, his golfing buddy, and his golfing buddy’s wife—stood ever ready to provide for reasonable fees most often covered by the Homeowner’s Policy. If

not the sort of thing you’d find in the yellow pages, still, tough work that someone had to do.

“Maybe you should just play whatever numbers come up Ed. Maybe ask for something that ends in zeros.”

At this Uncle Eddie’s visage changed—adopting the distant and bedazzled gape of the ancient Mayan perplexed by the delicate mysteries of nothingness.

Y

ears ago I would do it for nothing. I’d only

been in town a matter of months when the chief of police then, a fellow Rotarian, called the funeral home in the middle of the night to ask if we had anyone on the staff who took care of “the messes … you know, the really bad ones.”

“We’ve had a bad one over here on Highland Road. You’re getting the body, but he’s gone to the morgue. I just can’t let his family back in the house until something’s

done with it. Really bad.”

I wondered if the Chief imagined a door in the funeral home marked BAD ONES behind which specialists in “messes” waited for calls.

“Well, we don’t have anyone in particular, Chief, but I’ll be over and I’ll try Wes,” referring to Wesley Rice, our chief embalmer, a man from the old school who was well used to emergencies in the dark.

It seems the late mortgagee of

the split-level home on Highland Road had grown weary of his wife’s ongoing affair with the chiropractor for whom she worked. Details of the tryst were sketchy, the Chief said. It had all started with an “adjustment.” Push had apparently come to shove.

“Yep,” he said. “The eternal triangle.” He spit on the sidewalk in front of the house. “She’s taken the kids and gone to her sister’s place. Won’t

come back until it’s clean.”

The Chief had been able to piece it together, from physical evidence and the widow’s understandably agitated testimony. The cuckholded householder had sat up drinking after his wife had gone to bed, announcing her intention to put spongy rollers in her hair. This had become an intimate code that meant to him she did not want to have sex with him but wanted to look

good for the boss tomorrow. He’d finished the bottle of Dunphy’s Irish and raided her stash of Valium, then gone to the drawer where the Black & Decker electric carving knife was kept between Easters and Thanksgivings and Christmases. He’d plugged it into the wall socket on his side of the bed, locked his jaw against any utterance and, laying down beside her, applied the humming knife to his throat,

severing his two ascending carotid arteries and jugular veins and making it half through his esophagus before he released his hold on the knife’s trigger. It had not been his coming to bed, nor the buzz of the knife, nor any sound he’d made, if, indeed, he’d made any, that woke her. Rather, it was the warmth of his blood, which gushed from his severed blood vessels halfway up the master bedroom

wall and soaked her and her spongy rollers and saturated the bed linens and mattress and box springs and puddled in the carpet beneath the bed that woke her wondering was it just a dream.

Wes and I worked until daybreak. We removed the carpet and the mattress and box springs, tossed out the pile of magazines under the bed—soft porn and hunting and truck magazines on his side, catalogues and

Cosmopolitan’s

on hers. We soaked the knickknacks on the dresser in a

commercial cleaning solution, wiped the plastic surfaces that had red dots of blood: the phone the clock radio, the color TV. Then we painted the room, except for the ceiling, with paint we found in the basement. Where the blood had soaked through the carpet and padding and left a stain on the hardwood floor, we scrubbed for

a while, then left a towel saturated with bleach on it. We left then.

Wes, after much suturing and the use of a turtleneck sweater, was able to predict the possibility of an open casket, though nothing could be done about the dead man’s mouth, which was clenched in the way you see in the movies when they give the wounded hero a bottle of hooch and a bit of leather to chew before they remove the

bullet or the leg that the bullet was shot into.

The poor client looked, as a cousin several times removed remarked, “determined.”

This is the part I have always admired—the determination, the pure resolve, to do one’s self such massive and irreparable damage, which is the distinguishing element of all successful suicides. It distinguishes the true killer from the occasionally suicidal. Who

among us in our right minds hasn’t several times in the course of life yearned for the comforts of absence and non-being. But there is a subtle and important difference between those of us who’d rather not be alive tomorrow—incomplete homework, biopsy results, romantic reversals, pregnancy tests—and those of us who want to be dead, tomorrow and the day after and forever. The latter is the exception,

the former, the rule.

This holds true for homicide as well as suicide. Indeed, my own neuroses tend toward the aggressive rather than the depressive disorders—toward the destruction of others and away from the destruction of self since I, like most funeral directors, nurse a fantasy in which I am the last man on the face of the earth having discharged my sad and profitable duties of burying everyone

else, at which point I will be assumed into

any available heaven with all my bills paid for the first time in my life. Most of us have, often times, if only momentarily, hungered for someone to fall off the planet. Former spouses, dental hygienists, government employees, fellow commuters at rush hour, teenagers, telemarketers, TV preachers, in-laws, parents, perfect strangers (and who among us

isn’t one of these) have all been the objects of homicidal scorn. But most of us will not be killers because we understand the difference between being angry enough to kill and being a killer.

Still, the impulse to turn our pain outward is a sibling to the impulse to turn it on ourselves. Whether we are always to blame or never to blame, we are still the center of a hurtsome universe. Homicide

and suicide are verses of the same sad tune, close cousins of the one pathology.

To kill another of one’s own species—be it one’s “self” or one’s “other”—calls for true resolve and a deadly silence, however momentary, of all the voices raised to the contrary. Of course, many of the voices are institutional. Governments pass laws that make it illegal to murder one’s self or another. Religions

cite texts that proclaim it immoral and unforgivable. Life, they argue, is sacred, in every one of its human incarnations. It’s God’s to give and God’s to take away. Others extend such protections to endangered species, whales and snaildarters, owls and elm trees. This is the province of politicos and theologians. There are, notably, civil and ecclesiastical exceptions to these rules—hence, Holy Wars

and executions. Suicides and homicides in the name of God or Justice or Mercy or Self-Defense are acceptable deviations from the norm.

But the noisier voices are our own, the elements of the self—psychological, biological, spiritual, social, intellectual. Free of flag and icon, each still argues against its end. As anyone who has swatted a wasp, or caught a fish, or shot an animal, or sat with

the dying of our own kind knows, life—at a cellular level—rages against the dying of the light. Something in us argues, “Don’t!”

Post mortem caloricity, they taught us in mortuary school, was the name for the way the body warms immediately after death occurs. The cells keep dividing, metabolizing, exchanging oxygen and protein, doing their accustomed work. With no exhaust system—breathing, sweating,

weeping, farting—the system overheats. The cells shut down. Punch the clock. Call it a day. Then the dead body cools to room temperature, nearly thirty degrees cooler than the rest of us, accounting for one of our most frequently asked questions—why is it cold?

So there is a difference, an important difference, between when we die to our stethoscopes and encephalograms:

somatic

death; when we

die to our nerve ends and molecules:

metabolic

death; and when we die to those around us—grandchildren and creditors, siblings and neighbors—an end we might call our

social

death.

In the same way birth has its degrees—from conception (metabolic) to viability (somatic) to naming or baptism or initiation (social). The order in which these deaths and these births happen is important, and historically

we’ve shown a preference for the order I’ve outlined them in—our readiness and willingness to accept someone’s new life or new death and its implications for ourselves, following by hours or days or weeks or years, either their ability or their refusal to produce what we call “vital signs.” We do not baptize or name until we are reasonably certain the child will live and, as technology has increased

viability, we name and baptize our babies younger and younger. Likewise, we do not bury until we are reasonably certain a person is dead (the fear of live burial is an ancient one), and most rituals follow an effort to “wake” the alleged decedant—just to be sure.

Funerals, in every culture and history, have sought to nudge the bereaved toward an acceptance of The Facts just as baptisms or their

equivalents have sought to do the same for the fecund. And the rituals surrounding births and deaths provide a paradigm for the safe and sane management of the implications of a new dead body on the floor or a new live one.

Accordingly, ceremonial, symbolic, and practical considerations have always been addressed by such rituals. They address the needs of living and dead, newborn and parents.

At one end of life the community declares

It’s alive, it stinks, we’d better do something.

At the other end we echo,

It’s dead, it stinks, we’d better do something.

And ever since we emerged from the cosmos, garden, or the primordial ooze, we have called it Nature’s Way or God’s Will or The Great Mandala or The Facts of Life: we are born, we die; we love and grieve; we breed and disappear. And

whether God created nature or Nature created god, the natural and godly death is unwelcome while the natural and godly birth is a joy. Of course, there is a degree of ambivalence about both events. No birth is entirely wonderful or free of worries and no death is entirely awful, without its blessings and consolations. We may tolerate it, accept it, regard it as appropriate or merciful or timely.

Nonetheless, until just lately, birth has been the bundle of joy, the miracle of life; and death has been the unwelcome guest—the dark angel, the grim reaper, the thief in the night, the son of a bitch.