The Undertaking (17 page)

Authors: Thomas Lynch

Hard pressed to explain the imbalance himself, Dr. Jack, with characteristic indifference to his audience says, “It just seems that the ladies were asking for it.” The truth perhaps, but told in the impolitic idioms of an age of chivalry and cardigan sweaters by a late-century, oddly cavalier, heroically challenged idealogue.

Are these the messes, the really bad

ones, now: the questions we’d rather nobody asked?

The answers we each have are only our own. In the best case scenario, a majority rules. The majority can be dead wrong, of course, and often is. It’s the chance one takes on democracy. But just as we can’t only have the abortions we want or understand or could defend, we won’t just have the “easy” assisted suicides. For every victim of rape or

incest or life-threatening pregnancy who seeks an abortion there are several victimized by inconvenience or financial difficulties or emotional vexations. For every pain-wracked cancer patient there will be several deeply melancholic or acutely disturbed or bitterly indifferent but otherwise able-bodied applicants for assisted suicide. And just as we can’t withhold the guaranteed

abortion rights

of a woman aborting one of twin fetuses because she doesn’t feel she can afford two babies, emotionally or financially, we will not be able to withhold the guaranteed rights to assisted suicide to the young father who loses a job or the young woman who finds her husband in love with another. Where abortion is available on demand, should we really expect to moderate or regulate assisted suicide?

Where choice is enshrined we must suffer the choices.

Where life is sacred we must suffer the life.

U

nvexed by the existentials, should we not expect the marketplace to take over? The questions devolve from

whether or not

to

who is entitled

to

who’s going to pay

to

cash or charge?

to

do you take American Express?

O

f course, I can be wrong, too, and often am.

And I am preparing for the

possibility. Both Dr. Jack and I are thinking of clinics—

obitoria

he calls them—because if I cannot beat him, I can surely compete with him. I can outkevork him. It’s good for everyone. It keeps the prices down. And my guess is that once he has made his point, he’ll be too busy with talk shows and lecture tours to really stay home and take care of business.

I confess it has occured to me that

a tastefully unimposing annex to my current emporium here in Milford might be the obvious and proximate preference of my townspeople. Two or three thousand barrier-free, nonthreatening square feet, say, with plenty of big pillows in earthtone natural fabrics, a kind of “parlor” with New Age music piped in, a staff of appropriately frumpy helping professionals trained to assist with “end of life”

(the locally fashionable euphemism) decisions, exclusively motivational wall-treatments

(Love is Forever

or

Just Do It

imposed on a watercolor landscape of the Dolemites), reminiscent

in decor and concordance of nothing so much as one’s kindergarten classroom. And maybe a two- or three-unit crematorium attached, since, if we can believe the records here in Oakland County, nine out of every ten

assisted suicides is burned. Of course, in our obitorium, we’d offer choices—about disposition of the body, caskets, urns, types of services, officiants, music. Along with traditional burnings and burials, we’d offer scatterings in outer space, or virtual entombments in cyberspace. And certainly the method of medicide should be a choice—pistols or poisons or plastic bags, hangings or bridge jumps

or natural gas, and whether to do it on-site or at home or in one of our several designer locations—we have gardens, waterfalls, parks, and gazebos, all within walking distance. And whether to video or not is, naturally, a personal decision. And there would be several easy payment plans from which to, well, choose.

By a happy coincidence, our current holdings here in Milford take up most of a

block at the corner of Liberty and First Streets, making

The First Liberty Clinic

an aptly patriotic, almost churchy corporate name. Or maybe just

The Libertorium

? Or how about

Serenity Social Services, Inc.

—Triple S, again.

Don’t leave a mess, etcetera.

Then someone will have to be in charge of establishing federally mandated minimum standards for Meaningful Living, below which, it might prudently

follow, Social Security checks will be discontinued. Once life is meaningless, it oughtn’t to be a burden on the taxpayers. And just as our generation of policymakers has found that abortion is more cost effective than paying welfare, our children’s generation (already in arrears with our national debt) will find Medicide far better a bargain than Medicare. This will not

require

anyone to take

their voluntary leave of this life, but it may help to

educate

them as to their options/duties as a citizen. I bet there’ll be no shortage of bishops and politicos and actuarial agents in the next generation willing to serve on such a panel.

“The slippery-slope argument!” someone always says—as if to name it is to nullify it. As if things

don’t

go from bad to worse. As if gravity did not exist.

Most of us just want to keep our balance.

E

xcept, of course, for Dr. Kevorkian, whom history will record as a prophet. His attorney has suggested a Nobel Prize. His oils on canvas are all the rage. Can his own talk show be far behind?

Maybe Uncle Eddie was right all along. Maybe the handwriting’s on the wall. Maybe it’s only a matter of time. Maybe it’s not worth bothering over. He seems happier.

He gets more sleep. He has more time to spend with the family. He has no regrets.

He seems resigned to his decision to shut down Triple S. He gave away the novelty items, split the checkbook with his wife, his golfing buddy, and his golfing buddy’s wife. He had the 800 number disconnected. And one night, months later, puzzling with the letters of its now familiar digits, he noticed how they might

have spelled

NOTHING

. Nothing at all.

This would normally be the place to say (as critics of the American funeral trade invariably do), “I am not, of course, speaking of the vast majority of ethical funeral directors.” But the vast majority of ethical funeral directors is precisely the subject of this book.

—J

ESSICA

M

ITFORD

,

T

HE

A

MERICAN

W

AY OF

D

EATH

, F

OREWORD, P. VIII

She went to a long-established, “reputable” undertaker.

Seeking to save the widow expense, she chose the cheapest redwood casket in the establishment and was quoted a low price. Later, the salesman called her back to say the brother-in-law was too tall to fit into this casket, she would have to take the one that cost $100 more. When my friend objected, the salesman said, “Oh, all right, we’ll use the redwood one, but we’ll have to cut off his feet.”

—

IBID.

C

HAPTER TWO, P.

24

T

he same mortician who once said he’d rather give away caskets than take advantage of someone in grief later hung billboards

out by the interstate—a bosomy teenager in a white bikini over which it read

Better Bodies by Bixby

(not the real name) and the phone numbers for his several metro locations.

I offer this in support of the claim that there are good days and

there are bad ones.

No less could be said for many of the greats.

I’m thinking of Hemingway’s take on Pound when he said, “Ezra was right half the time, and when he was wrong, he was so wrong you were never in any doubt of it.” But ought we be kept from “The River-Merchant’s Wife” by his mistaken politics? Should outrage silence the sublime?

The same may be asked of Mr. Bixby’s two memorable

utterances.

Or, as a priest I’ve long admired once said, “Prophesy, like poetry, is a part-time job—the rest of the time they were only trying to keep their feet out their mouths.” I suppose he was trying to tell me something.

Indeed, mine is an occupation that requires two feet firmly on the ground, less for balance, I often think, than to keep one or the other from angling toward its true

home in my craw.

I sell caskets and embalm bodies and direct funerals.

Pollsters find among the general public a huge ambivalence about funeral directors. “I hope you’ll understand it if I never want to see you again,” the most satisfied among my customers will say. I understand.

And most of the citizenry, stopped on the street, would agree that funeral directors are mainly crooks, “except

for mine … ,” they just as predictably add. “The one who did my (

insert primary relation)

was really helpful, really cared, treated us like family.”

This tendency, to abhor the general class while approving of the particular member is among the great human prerogatives—as true of clergy and senators as it is of teachers and physicians. Much the same could be said of Time: “Life sucks,” we say,

“but there was this moment …,” or of racial groups: “Some of my

best friends are

(insert minority)

…,” or of gender:

“(Insert sex)

! You can’t live with them and you can’t live without them!”

Of course, there are certain members of the subspecies—I’m thinking lawyers, politicians, revenue agents—who are, in general and in particular, beyond redemption and we like it that way. “The devil you know’s

better than the one you don’t …” is the best we can say about politicians. And who among us wants a “nice” divorce attorney or has even one fond memory involving the tax man? Really, now.

But back to caskets and bodies and funerals.

When it comes to caskets I’m very careful. I don’t tell folks what they should or shouldn’t do. It’s bad form and worse for business. I tell them I don’t have any

that will get them into heaven or keep them out. There’s none that turns a prince into a frog or, regrettably, vice-versa. There isn’t a casket that compensates for neglect nor one that hides true love, honorable conduct, or affection.

I

f worth can be measured by what they do, it might help to figure out what caskets “do” in the inanimate object sense of the verb.

How many here are thinking

“handles”? When someone dies, we try to get a handle on it. This is because dead folks don’t move. I’m not making this part up. Next time someone in your house quits breathing, ask them to get up and answer the phone or maybe get you some ice water or let the cat out. He won’t budge. It’s because he’s dead.

There was a time when it was easier to change caves than to drag the dead guy out. Now

it’s not so easy. There’s the post office, the utilities, the closing costs. Now we have to remove the dead. The sooner the better is the rule of thumb, though it’s not the thumb that will make this known.

This was a dour and awful chore, moving the dead from place to place. And like most chores, it was left to women to

do. Later, it was discovered to be a high honor—to

bear the pall

as a liturgical

role required a special place in the procession, special conduct, and often a really special outfit. When hauling the dead hither and yon became less a chore and more an honor, men took it over with enthusiasm.

In this it resembles the history of the universe. Much the same happened with protecting against the marauding hordes, the provision of meaty protein sources, and more recently, in certain

highly specialized and intricate evolutions of food preparation and child care.

If you think women were at least participant and perhaps instrumental in the discovery of these honors, you might better keep such suspicions to yourself. These are not good days to think such thoughts.

But I stray again. Back to business.

Another thing you’ll see most every casket doing is being horizontal. This

is because the folks that make them have taken seriously the demonstrated preference of our species to do it on the level. Oh, sure—it can be done standing up or in a car or even upside down. But most everyone goes looking for something flat. Probably this can be attributed to gravity or physics or fatigue.

So horizontal things that can be carried—to these basic properties, we could add a third:

it should be sturdy enough for a few hundred pounds. I’m glad that it’s not from personal experience that I say that nothing takes the steam out of a good funeral so much as the bottom falling out.

And how many of you haven’t heard of this happening?

A

word on the words we’re most familiar with.

Coffins

are the narrow, octagonal fellows—mostly wooden, nicely corresponding to the shape of

the human form before the advent of the junk food era. There are top and bottom, and the screws that fasten the one to the other are often ornamental.

Some have handles, some do not, but all can be carried. The lids can be opened and closed at will.

Caskets

are more rectangular and the lids are hinged and the body can be both carried and laid out in them. Other than shape, coffins and caskets

are pretty much the same. They’ve been made of wood and metal and glass and ceramics and plastics and cement and the dear knows what else. Both are made in a range of prices.

But

casket

suggests something beyond basic utility, something about the contents of the box. The implications is that it contains something precious: heirlooms, jewels, old love letters, remnants and icons of something dear.

So casket is to coffin as tomb is to cave, grave is to hole in the ground, pyre is to bonfire. You get the drift? Or as, for example, eulogy is to speech, elegy to poem, home is to house, or husband to man. (I love this part, I get carried away.)

But the point is a

casket

presumes something about what goes in it. It presumes the dead body is important to someone. For some this will seem like

stating the obvious. For others, I’m guessing, maybe not.

But when buildings are bombed or planes fall from the sky, or wars are won or lost, the bodies of the dead are really important. We want them back to let them go again—on our terms, at our pace, to say you may not leave without permission, forgiveness, our respects—to say we want our chance to say goodbye.

Both coffins and caskets are

boxes for the dead. Both are utterly suitable to the task. Both cost more than most other boxes.

It’s because of the bodies we put inside them. The bodies of mothers and fathers and sons, daughters and sisters and brothers and friends, the ones we knew and loved or knew and hated, or hardly knew at all, but know someone who knew them and who is left to grieve.

I

n 1906, John Hillenbrand, the

son of a German immigrant bought the failing Batesville Coffin Company in the southeastern

Indiana town of the same name. Following the form of the transportation industry, he moved from a primarily wooden product to products of metal that would seal against the elements.

Permanence

and

protection

were concepts that Batesville marketed successfully during and after a pair of World Wars in which

men were being sent home in government boxes. The same wars taught different lessons to the British, for whom the sight of their burial grounds desecrated by bombs at intervals throughout the first half century suggested permanence and protection were courtesies they could no longer guarantee to the dead. Hence, the near total preference for cremation there.

Earth burial is practiced by “safe”

societies and by settled ones. It presumes the dead will be left their little acre and that the living will be around to tend the graves. In such climates the fantasies of permanence and protection thrive. And the cremation rate in North America has risen in direct relation to the demographics and geographics of mobility and fear and the ever more efficient technologies of destruction.

The idea

that a casket should be sealed against air and moisture is important to many families. To others it means nothing. They are both right. No one need to explain why it doesn’t matter. No one need explain why it does. But Batesville, thinking that it might, engineered the first “sealed” casket with a gasket in the 1940s and made it available in metal caskets in every price range from the .20 gauge

steels to the coppers and bronzes. One of the things they learned is that ninety-six percent of the human race would fit in a casket with interior dimensions of six feet six by two feet high by two feet wide—give or take.

Once they had the size figured out and what it was that people wanted in a casket—protection and permanence—then the rest was more or less the history of how the Hillenbrand

brothers managed to make more and sell more than any of their competition. And they have. You see them in the movies, on

the evening news being carried in and out of churches, at gravesides, being taken from hearses. If someone’s in a casket in North America chances are better than even it’s a Batesville.

W

e show twenty-some caskets to pick from. They’re samples only. There are plenty more

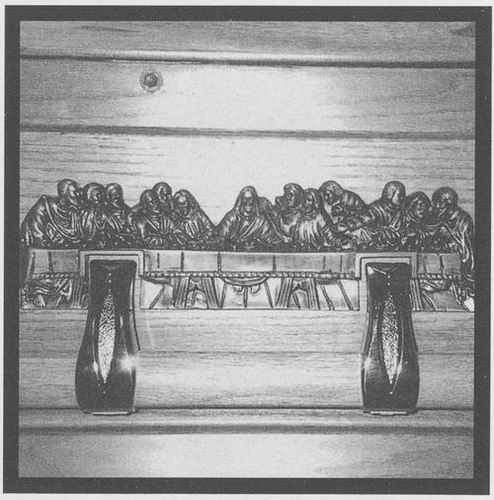

we can get within a matter of hours. What I carry in blue, my brother Tim, in the next town, carries in pink. What I carry tailored, Tim carries shirred. He carries one with the Last Supper on it. I’ve got one with the Pietà. One of his has roses on the handles. One of mine has sheaves of wheat.

You name it, we’ve got it. We aim to please.

We have a cardboard box (of a kind used for larger appliances)

for seventy-nine dollars. We also have a mahogany box (of a kind used for Kennedys and Nixons and Onassises) for nearly eight grand. Both can be carried and buried and burned. Both will accommodate all but the tallest or widest citizens, for whom, alas, as in life, the selection narrows. And both are available to any customer who can pay the price.

Because a lot of us tend to avoid the extremes,

regardless of how we elect to define them, we show a wide range of caskets in between and it would look on a chart like one of those bell curves: with the most in the middle and the least at either end. Thus, we show three oak caskets and only one mahogany, a bronze, a copper, a stainless steel, and six or seven regular steels of various gauges or thicknesses. We show a cherry, a maple, two poplars,

an ash, a pine, a particle board, and the cardboard box. The linings are velvet or crepe or linen or satin, in all different colors, tufted or ruffled or tailored plain. You get pretty much what you pay for here.