The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage (5 page)

Read The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage Online

Authors: Jan Morris

Tags: #Mediterranean Region, #Venice (Italy), #History, #General, #Europe, #Italy, #Medieval, #Science, #Social Science, #Human Geography, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues

As you step ashore into the tumult of it all (fragrance of frying fish from the floating restaurants by the Galata Bridge, tinkle of brass bell from the water-seller outside the Egyptian Bazaar,

swoop of dingy pigeons around the mosque of Yeni Cami) – as you edge your way into the crowd you know at once that you are entering a great presence, which displays even in its modern impotence the stance of old majesty.

If sailing to Byzantium feels like this today, imagine the sensations of the Crusaders as

they

sailed out of the Marmara on 24 June 1203, their purpose now revealed to them all! Istanbul is not even the capital of Turkey: Constantinople was the capital of half the world. It was also one of the supreme cities of the Christian faith: deep though the gulf was between the Latin and the Orthodox rites, Constantinople was a city to be reverenced even by Catholics. ‘I can assure you,’ says Villehardouin, ‘those who had never seen Constantinople before gazed very intently at the city, having never imagined there could be so fine a place in all the world.’

There was no mistaking the historical impact of the occasion, or its beauty. ‘It was something so beautiful as to be remembered all one’s life.’ The fleet, so Villhardouin thought, ‘seemed as it were in flower’, spread out in magnificent array across the Marmara under a cloudless sky: first the terrible war-galleys, rowed with a steady stroke, then the mass of tall transports, and then like a cloud behind, as far as the eye could see, all the small craft of the fleet-followers, the independent fortune-hunters, the hopeful entrepreneurs, the rogues and scavengers, who had attached themselves to the Crusade on its progress to the east.

To the soldiers from France, Belgium or Germany, Constantinople was more than just a city, it was a myth and a mystery. The Russians called it Tsarigrad, Caesar’s City, the Vikings Mickle Garth, the Mighty Town, and it had long before entered the legends of the west. Young men grew up with a vision of it. The City on its seven hills, the grand repository of classical civilization – the greatest city of them all, rich beyond imagination, stuffed with treasures new and ancient, where the wonders of ancient learning were cherished in magnificent libraries, where the supreme church of Santa Sophia, the church of the Holy Wisdom, was more like a miracle than a work of man, where countless sacred relics were kept in a thousand lovely shrines, where the emperor of the Byzantines dressed himself in robes of gold and

silver, surrounded himself with prodigies of art and craftsmanship, and lived in the greatest of all the palaces among the palaces of the earth, the Bucoleon. It was the City of the World’s Desire. It was the God-Guarded city. It was the city of the Nicene Creed – ‘Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible!’

For the worldly-wise Venetians the sight of the city doubtless provided

frissons

of another sort. It was not so strange to them. Many of the sailors had been there before. Countless others had relatives who had traded there or worked in the shipyards. There was a large Venetian colony in the city at that moment. To the Venetians, especially perhaps to the old Doge Dandolo as he scented the air of Byzantium upon his nostrils, it was not the sight of Constantinople that was exciting that day, but the circumstances of this landfall. Never before had a Venetian fleet approached the city in such overwhelming force, carrying an army of the strongest and fiercest soldiers in Europe, and bringing with it too, as the Doge’s particular puppet, a claimant to the imperial throne – Young Alexius, who had eagerly acquiesced in the plan for his future, and joined the fleet at Zadar.

Crusaders though they were, sailing to a Christian city, they made no attempt at a peaceful approach. When some of those fishing boats got in the way, they instantly attacked them; and when the fleet sailed, as we did, close under the walls of the city, the soldiers on deck were already cleaning their weapons for battle. It was the feast day of St John the Baptist, whose head was among the most precious of the relics enshrined in Byzantium: the ships flew all their flags in honour of the saint, and the noblemen hung out their decorated shields again all along the gunwales.

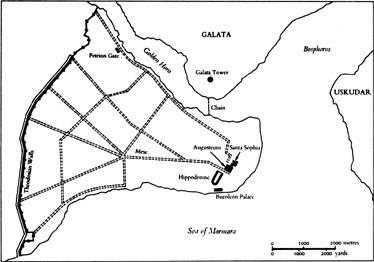

The people of Constantinople swarmed to the ramparts in their thousands to watch the fleet sail in. The soldiers looked back in awe at the walls towering above their ships. This was the most perfectly fortified city in the world. On its landward side, cutting off the peninsula from the mainland of Thrace, were the celebrated walls built by Theodosius II in the fifth century: four and a half miles long, and elaborately constructed in four lines of defence – moat and three walls. Then all along the shoreline, enclosing the entire peninsula, a sea-wall protected the city

against amphibious attack. Some four hundred towers commanded these encircling defences, and behind them underground reservoirs, granaries and innumerable windmills made the city self-sufficient for months of siege. A huge chain, controlled by a winch on a hill above, blocked the entrance to the Golden Horn. The imperial army was concentrated within the capital, and at the core of it was a formidable praetorian guard of Danish and English mercenaries, the Varangian guard.

Nobody had ever cracked these defences. For a thousand years they had kept the barbarians at bay. Six times Muslim armies had been beaten back from them; Goths, Huns, Hungarians, Bulgars, Serbs had all been repulsed. No wonder the Crusaders eyed the walls of Constantinople thoughtfully as they sailed by. ‘There was indeed no man so brave and daring,’ says Villehardouin convincingly, ‘that the flesh did not shudder at the sight…’

The fleet anchored on the other side of the Bosphorus, on the Asian shore. The army encamped itself at Scutari, now Usküdar, where Florence Nightingale had her hospital six centuries later and where now, from the big turreted railway station on the waterfront, the trains run away to Anatolia, Aleppo, Baghdad and Teheran. The soldiers looted the surrounding countryside for victuals and souvenirs: the leaders of the Crusade took over one of the Byzantine Emperor’s several country palaces. It was an ominous scene from the battlements of Constantinople, across the water. You can easily see from one shore to the other, and the huge encampment on the foreshore there, its smoke in the daytime, its lights at night, the forested riggings of its ships off-shore, must have cast a chill in the heart. What was that great host preparing? Was it merely passing by, or was it inexplicably, beneath the banner of the Cross, about to attack this ancient fortress of Christ?

The emperor did not wait to find out. His fleet, ramshackle in the Golden Horn, was in no condition to tackle the Crusade, but within a couple of days a squadron of his cavalry did ride down upon the Scutari encampment, being humiliatingly driven off. Two days later the Crusaders declared their purpose. They put Young Alexius on the deck of a warship, and displayed him

below the walls of the city. They had come, they shouted, to place him upon the throne, since he was the true king and natural lord of Byzantium. ‘The man you now obey as your lord rules over you with no just or fair claim to be your emperor, in defiance of God and the right. Here is your rightful lord and master. If you rally to his side you will be doing as you ought, but if you hold back, we will do to you the very worst that we can.’

These were specious arguments (long-winded, too, to be yelled into the wind from the deck of a galley) and the people’s predominant response, as they looked down at the Young Alexius, was ‘Never heard of him!’ Succession by coup or revolution had always been a feature of the Byzantine monarchy, and it was the accepted form for the populace to transfer their loyalties to a new emperor, however bloodily he had come to power. There was no suggestion that the people of Constantinople thought of Alexius III as an unlawful usurper. Hardly a single citizen defected from the imperial cause to join the pretender, just as nobody tried to rescue his blinded father Isaac, now old and derelict, from the dungeons in which he had so long been immured.

So it had to be done by force. On 5 July 1203, the first assault ships crossed the Bosphorus, each galley towing a transport, and made for the mouth of the Golden Horn. Most previous assaults on Constantinople had been from the landward side, the attacking armies beating themselves vainly against Theodosius’s tremendous walls. Dandolo knew that the weakest part of the defences was the sea-wall along the Golden Horn. The Horn was unbridged in those days, and on its northern bank, opposite Constantinople proper, was the foreign quarter of Galata, where the trading colonies were settled, and the envoys of the powers were all obliged to live. Halfway up its hill stood the massive Galata Tower, and from it ran the chain across the entrance to the Golden Horn: it was 1,500 feet long, with links the length of a man’s forearm, and it was suspended a few feet above the surface of the water.

Once through this chain, and the Crusaders would be under the lee of the city on its weakest side. The walls along its northern shore were feeble compared to the others, without moats or

enceintes

, and made difficult to defend by the steep streets running

directly down the hills behind them. Dandolo, the tactician of the assault, accordingly ordered the first landing to be made on the Galata shore. There was no resistance. At the first sight of the Norman knights on their armoured horses, led by grooms out of the sally-ports of the assault craft, the Greek forces fled from the waterfront, and in no time a bridgehead was established. Next day they captured the Galata Tower, after a stiff fight, and winched down the chain across the Horn. In sailed the warships, led by the mighty

Aquila

, into the crowded waterway, storming and burning whatever ships they found there: and so by 6 July the flank of the city was turned, and they were ready to storm it.

From the middle of the Ataturk Bridge, the higher of the two bridges that now span the Golden Horn, one may see almost exactly the view the soldiers saw, as they planned their assault from the decks of their warships. This is visibly the city’s soft side. It has none of the piled, phalanx look that characterizes Constantinople from the Sea of Marmara. Here all the muddled bazaars, speckled with small mosques and splashed here and there with green, give the place a rather helpless look, and the great buildings along the skyline, which look so forbidding from the sea, seem almost avuncular from the Golden Horn.

Along the shoreline you can make out the remains of fortifications. It is a sleazy shore there, a slum of small warehouses and factories, old houses crumbled into squalor, small boatyards where the caiques are caulked, tanneries and tyre depots. Big ships do not moor here, only grubby coasters from the Anatolian islands, their masts shipped, their crews wearing cloth caps and eating fried fish sandwiches out of carrier bags. But not quite obliterated by the confusion, still just distinguishable against the warren of streets on the hillside behind, turrets stand shadowy, and city gates reveal themselves. In 1203 this line of walls was complete, and joined the Theodosian walls at the head of the Golden Horn. Its turrets were manned all along the water’s edge, and there was no way of turning it. This was the one place, though, where the defences of Constantinople might be broken – by the skills not of soldiers, who had invariably failed to take this city, but of sailors, who had never tried before.

For it was the Venetians themselves who mounted the assault here, on 17 July 1203. The French decided to march to the head of the Horn, along its northern bank, and attack the Theodosian walls at the point where they joined the sea-wall on the waterfront. The Venetians resolved simply to hurl themselves across the Horn, a very Dandolan device. The point that they chose as the fulcrum of their attack can be identified. It is a rotted mass of masonry still called the Petrion Gate, immediately below the modest residence of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch, the Pope of eastern Christendom, who still lives in somewhat prickly circumstances in this Muslim and less than philhellene city. If you run your eye along the line of the waterfront buildings, you may identify almost exactly the site of the first landing: a small grubby square, with a struggling tree or two, beside the remains of the gateway at the water’s edge.

In the small hours of every morning they open the Ataturk Bridge to let the ships go through, and then, with the flashing of the lights, the beat of the engines, the slow movement of the vessels down the waterway in the dark, you can best imagine the Venetians preparing for their assault before the dawn of the battle. The fleet’s room for manoeuvre was awkwardly small. The Horn is only half a mile wide there, the tide runs fast, and somehow several score ships had to be navigated across this narrow channel simultaneously. The waterway was jammed full with their threshing oars and creaking hulls, and the later Venetian artists, when they came to recall this epic moment in the idealized historical reconstructions they were fond of, rendered it confusedly. In an excitable version I have before me now, for instance, the Golden Horn seems to be one solid mass of warships, all ropes, masts, spars, oars and ladders, and one peers along the walls of Constantinople through a curtain of arrows and plunging missiles. Sailors clutch yard-arms, arrows plunge into knightly shields, axemen hack each other, men-at-arms fall upside-down into what little can be seen of the water.

But serenely dominating the picture, armoured on the foredeck of his flagship, is old blind Dandolo, holding a flag and pointing firmly towards Santa Sophia. This, it seems, is perfectly just, for he really did lead the assault. If he could not actually see the walls,

Constantinople, 1203

Constantinople, 1203