The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (32 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

As the quality of air deteriorated through the century, so did the water, a process that began at the beginning of the century, from a combination of factory waste, contamination from gasworks, the dockyards releasing ‘copper and other ingredients’, and dozens of other industries flushing out their own chemical brews into the Thames. As early as 1821, an inquiry presided over by the Lord Mayor looked at river water near the gasworks. Live fish were put into buckets of locally collected water: the flounders died within a minute of immersion, while eels lasted four minutes.

The problem of industrial waste was dwarfed by the problem of human waste. Too many people living in one place were all discharging their effluent into the Thames. By 1828, nearly 150 sewers were disgorging into the Thames between Vauxhall Bridge and Limehouse alone, and by the 1850s the city’s central sixty sewers daily flushed 260 tons of raw sewage directly into the river. And because the Thames is tidal, this pollution was being washed right back twice a day: as the tide ebbed, shorelines of ‘mud’ 125 yards wide were revealed, ‘mud’ that was raw sewage.

Summoning the political will to deal with the problem took decades, long after the increase in population had overwhelmed the civic infrastructure. The Bill of Sewers legislation – defining sewers purely as conduits for rainwater and entirely prohibiting their connection to house drains – had passed three centuries earlier and was still in force. According to the law, cesspools, not sewers, were for sewage. For centuries, therefore, cesspools under houses had been where all human waste was disposed. Even if cesspools were cleaned regularly, in densely populated districts they were still offensive; when they were not cleaned regularly, they were almost beyond imagining. The latter was often the norm: cesspools were expensive to clean and the process was unpleasant. To minimize the disruption, by the middle of the century emptying cesspools was confined to the hours between midnight and 5 a.m. Five night-men were usually required to clean one cesspool. A holeman descended to fill the tubs lowered by the ropeman;

two tubmen then carried the tubs back and forth out to the street, where the fifth man emptied the loads into an open cart. (In most London houses, few of which had rear access, these tubs were carried one by one through the interior.) Until 1848, this waste was taken to nightsoil yards, where it was mixed with exhausted (used) hops, bought cheaply from the breweries, and spread out to dry, wafting its scent across the neighbourhood until it was in a condition to be sold as fertilizer.

Those with less money, or those in rental properties whose landlords wanted to scrimp, had their cesspools cleaned infrequently; the poor, or those with bad landlords (which was often the same thing), never had them cleaned at all. By the late 1840s, there were so many cesspools under even the most expensive housing in the West End, that the walls between them frequently collapsed, and so fashionable London was perched on top of what one sanitary reformer called not cesspools but ‘cess-lakes’. These noxious lakes filled up and overflowed, the liquids soaking into the ground and ultimately contaminating the water, while the solids slowly seeped into neighbouring cellars and streets, oozing up through the bricks every time it rained. In St Giles, ‘whole areas of the cellars were full of nightsoil to the depth of three feet’ and yards were ‘covered in nightsoil...to the depth of nearly six inches’.

The number of animals in the city added to the filth. Many city dairies kept cows, often in cellars, where they were fed through hatches, with their waste removed the same way. In 1829, the student Hékékyan Bey went to look at lodgings in Parliament Street: on finding that half the courtyard was given over to four dairy cows he declined, but such arrangements were not unusual.

66

By 1837, a guidebook suggested there might have been as many as 10,000 cows in London dairies, fed not on hay but on spent mash from the breweries. A decade later, this figure had doubled; many animals were kept under the newly built railway arches by the Thames, forty or fifty cows

per arch, and fed on market sweepings. At mid-century, Westminster, near one of the slums around St James’s, was home to ‘14 cow-sheds, 2 slaughter houses, 3 boiling houses [most likely boiling horses for glue], 7 bone stores, [and] 1 zincing establishment’.

Animals were found throughout the city. At Millbank prison, once surrounded by a moat, a cow was kept in the 1850s to crop the ditch’s grass; Westminster Abbey and Green and Hyde Parks all had sheep and cattle to keep the grass down. (Hyde Park leased its grazing rights to butchers, and the odd goat, too, was to be found there.) Throughout both town and suburbs, many people kept chickens and other fowl. As well as those owned by the watermen on cabstands, fowl routinely pecked and scratched outside the Old Bailey on Sundays, when there was less traffic, while Thomas Carlyle in Chelsea was tormented by the night-time crowing of a cockerel next door. Dickens placed chickens outside the fictional Newman Noggs’ Soho lodgings in

Nicholas Nickleby

, and David Copperfield’s aunt suspects all London chickens to be cellar-reared and exercised at the local hackney stands.

At least those who owned chickens annoyed their neighbours with nothing more than droppings with a powerful smell of ammonia. Many of the working-class population also raised pigs at their lodgings. Notting Dale was notorious for the smell of piggeries, while Jacob’s Island was just notorious for the smell. Here there was no way of dispersing the waste from the pigs, or even from the humans, for the privies were built over a huge ditch, ‘the colour of strong green tea’, into which the waste dropped, and from which the residents then drew their drinking water. They had begged the landlords for piped water, but for more than two decades the reply was that the lease was about to expire, so it wasn’t worth the expenditure.

Flush lavatories, which had at first appeared to be the solution for the problem of human, if not animal, waste, in actuality worsened the situation. By adding water to the waste as it was flushed, cesspools filled up ‘twenty or more times as fast’, and with liquids rather than solids, which made them more difficult to clean. In 1844, the Metropolitan Buildings Act reversed the prohibition on house drains being connected to the sewers: now such a connection was mandatory, to wash the waste from the city into the river,

and from there out to sea. But all that happened was that ‘The Thames is now made a great cesspool instead of each person having one of his own.’ To compound the problem, by mid-century urban sprawl had pushed the market gardens that took the waste-turned-fertilizer ever further away and the economic returns of transporting it were diminishing. When in 1847, guano, concentrated bird excrement, began to be imported as fertilizer, the market for normal waste collapsed, with prices halving. Soon farmers found they could refuse to pay for waste entirely, the nightsoil men being pleased to find anyone at all to take it.

Before flush lavatories could become commonplace, one thing was needed: running water. Until the 1870s, after Dickens’ death, a household’s water supply was a private contract, rather than a civic right. In 1847, of 270,000 houses in the City, 70,000 had no piped water. In less prosperous and more rural Fulham, in 1856, of 1,009 houses, only 147 paid for company water to be pumped into their houses. By then the Waterworks Clauses Act had been in force for a decade. It laid down that constant piped water had to be supplied to all dwellings in London, but that meant only that mains had to pass near by; it was up to individuals to connect their house to those mains. ‘Constant’, even for the mains supply, was a matter of interpretation: there was no mechanism for enforcing the legal requirement, so the water companies did as they pleased. In 1874, 0.3 per cent of Chelsea houses had running water twenty-four hours a day, and the average across the city was 10.3 per cent. It was not until the twentieth century that a citywide figure of 100 per cent was reached.

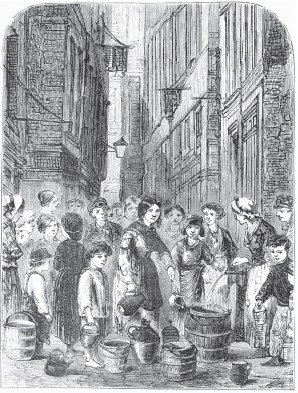

Throughout the century, therefore, street pumps were ubiquitous. In 1860, behind fashionable Bond Street, in Savile Row – then the location of prosperous doctors, as Harley Street is today – Dickens watched outside Albany, a stylish set of chambers, as the doctors’ menservants pumped up supplies for the maidservants of local tradesmen. In less prosperous neighbourhoods, those without servants to pump up water at the street pumps or collect it from the standpipes had to do it themselves. In 1854, one shopkeeper was found to have stolen his neighbours’ water. The mains passed through his shop, and he had bored a small hole in the pipe so that he no longer had to join the crowds ‘struggling and fighting’ for access to

the pump in those hours when the water was running: ‘there being so many of them, and so little water’.

Those with no alternatives had good reason to struggle and fight. Some companies, like the East London Water Company, provided what was considered to be a good supply: two hours, three times a week. Standpipes were placed in better streets every three or four houses, but in the courts and alleys they were to be found ‘every 8, 12, 20, or even 30 houses’. In such places the standpipes tended to have no taps: when the water company turned on the water for the requisite hours, the water gushed out until it was turned off at the mains again. In paved streets this ensured the paving was regularly washed, but in the unpaved courts two hours of running water created lagoons of mud, which ran into the nearby privies and in turn swilled the waste back out.

As the water ran at fixed hours, if the householders were out at work at the time, then they had to do without. Even if they were at home, they needed to have enough utensils to hold a forty-eight-hour supply of water. Many courts shared a single communal cask that filled up when the mains water ran, but these were generally uncovered and, for lack of any other space, were situated near the privies. They also had no taps: all the residents dipped in their own, necessarily unwashed, receptacles to collect their share. For one house in Rose Street, Covent Garden, with forty inhabitants, their 110-gallon cask was filled three times a week, meaning each resident had a ration of just under three gallons of water a day, for washing themselves, their clothes, their houses and their privies, for cooking and for drinking.

67

They were, they said, better off than most. Water companies were obliged by law to turn on the water if there was a fire, for the fire engines. The sanitary reformer George Godwin said that in one backstreet slum ‘while he was talking to a woman, an alarm of a house on fire resounded through the street. She exclaimed suddenly with pious gratitude, “Thank God...We will soon get some water.”’

Public baths, which began to appear in the 1840s and often included laundry facilities, were a partial solution for some. In the previous decade, prosperous men had enjoyed their own luxury version (without the laundry facilities), where they indulged in cold plunges, warm baths, sea-water baths, ‘tepid swimming-baths’, ‘medicated vapour’, ‘warm, cold, shower and chalybeate’ (medicinal spring-water) baths – ranging in price from 1s to an astronomical 7s 6d. Some baths listed additional enticements including ‘shampooing’, or massage. In the 1860s, the Jermyn Street Baths were the latest in opulence, with cushions on the floor, ‘divans, sofas, and all sorts of luxurious seats’, an ‘oblong marble tank filled with clear water’, around which bathers lay sleeping; a hot and a very hot room, a sluice room for post-massage, a cool room and a plunge pool. After all the massaging, sweating and sluicing, visitors were dressed ‘à la Turque’, complete with turban, before finishing off the visit with a pipe and a cup of coffee.

Baths for gentlemen, of greater or lesser opulence, were to be found across London: south of the river in Camberwell, north in Albany Place, York Road, near Regent’s Park, and particularly in areas around the clubs: in Suffolk Place, Pall Mall East and at Mivart’s Hotel (later renamed Claridge’s). These baths were sometimes called ‘hummums’, or ‘hammams’. The Hummums, with a capital H, referred to an establishment in Russell Street, Covent Garden, which had started off as a baths, but had transformed itself into a hotel, although one where irregular hours were the norm, ‘chiefly for bachelors’; Pip in

Great Expectations

knows that ‘a bed was always to be got there at any hour of the night’.

The poor were not regaled with Turkish costumes and coffee, but baths provided welcome help. In 1845, the first baths for the destitute of the East End were opened in Glasshouse Yard; more opened in 1846 near Euston Square. Here alone, within the first two years, 111,788 baths had been taken and 246,760 laundry-washes done. The following year an establishment designed by sanitation experts opened in Goulston Square, Whitechapel, with first-class and second-class facilities: cold and warm second-class baths for 1d and 2d, or cold and warm first-class baths for 3d and 6d. In the same year the Baths and Washhouses Act permitted parishes to set aside funds for building bathhouses, some of which opened their laundries ‘Gratuitously to the very Poor during the prevalence of the Epidemic’.

68