The Way of the Knife (41 page)

Read The Way of the Knife Online

Authors: Mark Mazzetti

Tags: #Political Science, #World, #Middle Eastern

He lit a cigar and turned philosophical.

“I think the Treaty of Westphalia is over,” he said. He was talking about the seventeenth-century peace accords in Europe that ended the Thirty Years’ War, three bloody decades of fighting among kings and emperors who sometimes used mercenaries as cannon fodder for the major battles. The Treaty of Westphalia, most historians agree, led to the birth of modern nations, standing armies, and national identities.

“Nation states no longer have a monopoly on military force,” he said. It was corporations and private interests, he said, that would be the future of America’s wars. “Just look at our own system. The only thing that isn’t outsourced is the guy shooting the gun.”

It was a rare moment when Dewey Clarridge was actually understating a situation. At times since the attacks of September 11, 2001, the United States had even outsourced the trigger pulling. Whether it was Erik Prince, Enrique Prado, and Blackwater hired by the CIA to hunt terrorists, or hired muscle like Raymond Davis driving through the streets of Lahore with a Glock semiautomatic in his glove box, or private soldiers dodging mortars during an all-night firefight on the roof of a CIA base in Benghazi, the chaotic first years of America’s shadow war had seen the United States willing to farm out government’s most elemental function: protecting the state.

It was getting late, and I got up to leave. Clarridge decided to stay and finish his cigar. We shook hands, and I walked to my car. Driving away, I glanced back at Dewey, sitting alone at the table of the retirement home’s empty restaurant. A thin trail of cigar smoke curled up into the dying light.

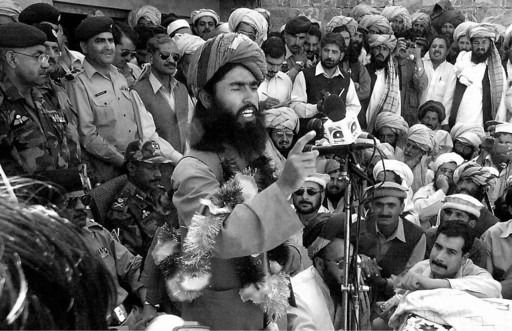

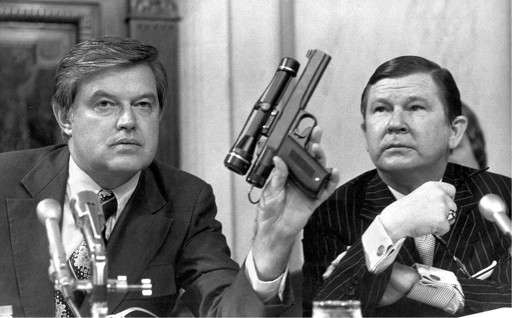

Senator Frank Church, holding a gun the CIA had built to shoot poison darts, led an investigation into CIA assassination operations during the spy agency’s early years. The hearings led to greater congressional oversight of the CIA and the agency abandoned lethal activities for decades.

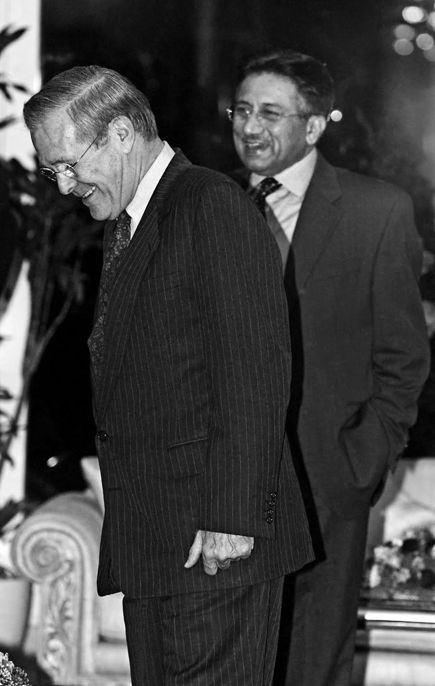

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld (left) was angry that the military was slow to begin its invasion of Afghanistan. He sought to expand the Pentagon’s special-operations capabilities and to broaden his department’s legal powers to wage war across the globe. President Pervez Musharraf of Pakistan (right) refused to allow American ground troops inside Pakistan but gave his blessing to CIA drone flights.

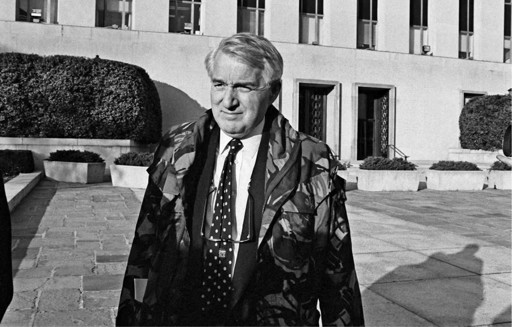

Duane “Dewey” Clarridge, a spy of the old school, was in charge of the CIA’s covert wars in Latin America during the Reagan administration. He later founded the agency’s Counterterrorist Center. Clarridge, who was indicted for perjury for his testimony on the Iran–Contra scandal, is pictured here leaving court in 1991.

He received a presidential pardon and reemerged years later as one of the principal figures in a spying operation run by the Pentagon to collect intelligence in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Following a bitter fight inside the CIA about whether the agency should get back into the killing business by using armed drones, the Predator has become one of the most widely used weapons of America’s secret war. Both the CIA and the Pentagon have conducted hundreds of drone strikes, from Iraq and Afghanistan to Pakistan and Yemen.

President Ali Abdullah Saleh of Yemen, pictured with a knife in his belt, became a counter-terrorism partner for Presidents Bush and Obama. He allowed both the CIA and the Pentagon’s Joint Special Operations Command to operate inside his country. A CIA Predator strike in Yemen in 2002 was the spy agency’s first drone strike outside of Afghanistan.

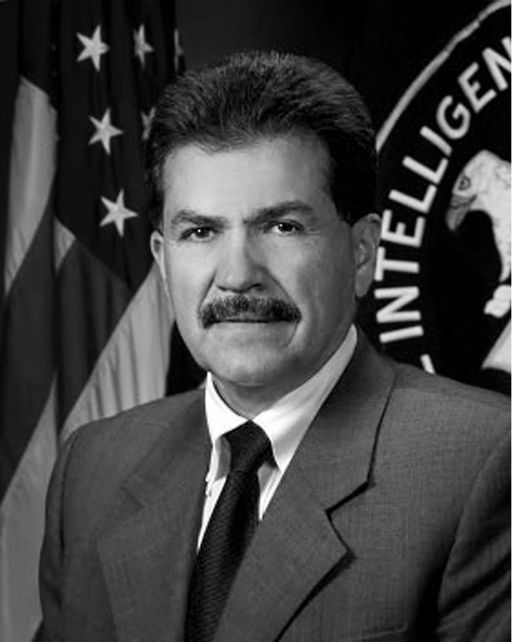

Jose Rodriguez spent his career in the CIA’s Latin America division before joining the agency’s Counterterrorist Center (CTC). As the leader of the CTC, and eventually as the head of all clandestine operations, Rodriguez accelerated the CIA’s transformation into a paramilitary agency.

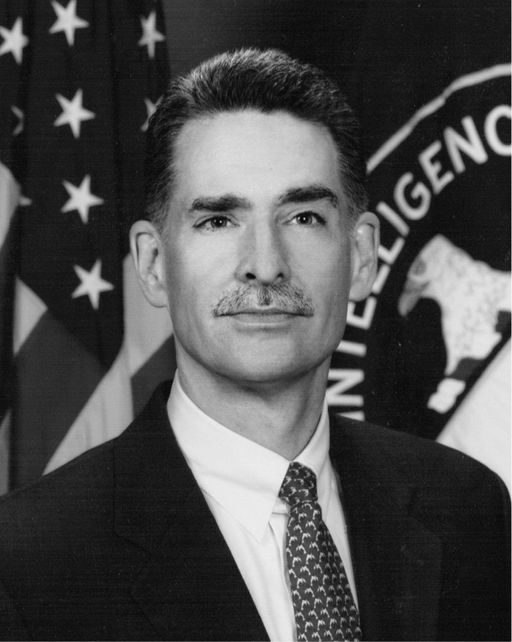

Ross Newland joined the CIA in the late 1970s when the spy agency was trying to refocus on foreign espionage activities after being chastened by the Church Committee investigation. He served as a clandestine officer in a number of Latin American capitals and was the CIA station chief in Bucharest, Romania, during the fall of Communism. When the September 11 attacks occurred, he was one of a small group of senior officers at Langley overseeing the Predator program.

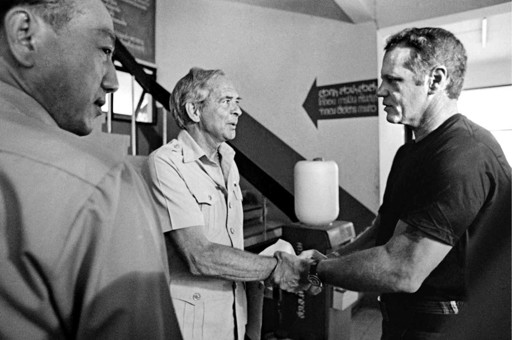

James “Bo” Gritz (right), a former Green Beret, organized a privately funded mission during the 1980s to rescue American POWs he believed were being held in central Laos. The Intelligence Support Activity, an obscure Pentagon spying unit, supported Gritz’s mission without notifying the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who had been planning a parallel rescue mission. In the years before the September 11 attacks, the Pentagon’s human spying activities were uncoordinated and resulted in several internal investigations.