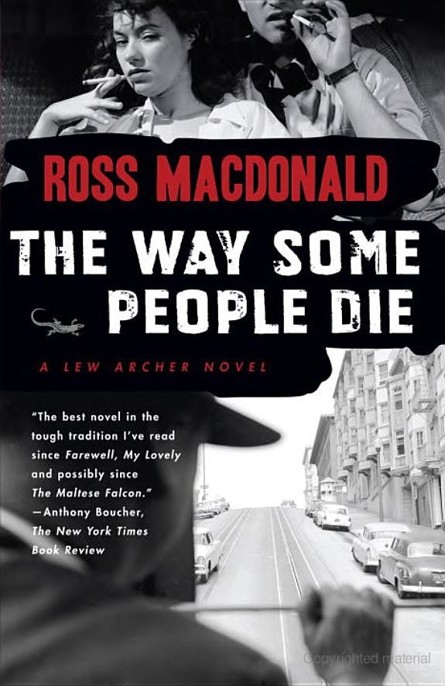

The Way Some People Die

Read The Way Some People Die Online

Authors: Ross Macdonald

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Hard-Boiled

THE WAY SOME PEOPLE DIE

Ross Macdonald’s real name was Kenneth Millar. Born near San Francisco in 1915 and raised in Ontario, Millar returned to the U.S. as a young man and published his first novel in 1944. He served as the president of the Mystery Writers of America and was awarded their Grand Master Award as well as the Mystery Writers of Great Britain’s Gold Dagger Award. He died in 1983.

The Dark Tunnel

Trouble Follows Me

Blue City

The Three Roads

The Moving Target

The Drowning Pool

The Ivory Grin

Meet Me at the Morgue

Find a Victim

The Name Is Archer

The Barbarous Coast

The Doomsters

The Galton Case

The Ferguson Affair

The Wycherly Woman

The Zebra-Striped Hearse

The Chill

Black Money

The Far Side of the Dollar

The Goodbye Look

The Underground Man

Sleeping Beauty

The Blue Hammer

FIRST VINTAGE CRIME/BLACK LIZARD EDITION, JULY 2007

Copyright © 1951 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

,

copyright renewed 1979 by Ross Macdonald

All rights reserved. Published in the United States

by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc.,

New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada

Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover

in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.,

New York, in 1951.

Vintage is a registered trademark and

Vintage Crime/Black Lizard and colophon

are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition

as follows:

Macdonald, Ross.

The way some people die [by] John Ross Macdonald [pseud]

New York, Knopf, 1951.

p. cm.

P23. M59943

51011053

eISBN: 978-0-307-77286-2

v3.1

To Roddy and Zella

CHAPTER

1

:

The house was in Santa Monica on a

cross street between the boulevards, within earshot of the coast highway and rifleshot of the sea. The street was the kind that people had once been proud to live on, but in the last few years it had lost its claim to pride. The houses had too many stories, too few windows, not enough paint. Their history was easy to guess: they were one-family residences broken up into apartments and light-housekeeping rooms, or converted into tourist homes. Even the palms that lined the street looked as if they had seen their best days and were starting to lose their hair.

I parked in front of the number I had been given and leaned sideways in the seat to have a look at the house. The numerals, 1348, were made of rusted metal and tacked diagonally across one of the round porch pillars. A showcard above, printed black on white, offered

ROOMS FOR TOURISTS

. There were several rattan chairs and a faded green glider on the porch, which covered the width of the house. A second-story porch, with more rattan, was surrounded by a wooden railing that looked unsafe. The third story had Gothic-looking towers at each corner, fake battlements that time had taken and made ridiculous. The roller blinds were low over the windows on all three levels, so they stared at me sleepy-eyed.

The house didn’t look as if it had money in it, or ever would have again. I went in anyway, because I’d liked the woman’s voice on the telephone.

She came to the door in a hurry when I knocked. A tall woman in her fifties with worried vague dark eyes in a worried long face, a black crepe dress over a thick corseted body. A detective was an occasion in her life. Her iron-gray hair

was set in a sharp new wave that smelt of the curling-iron, her nose and cheeks and chin were stark with powder. The light fell through the purple glass in the fanlight over the door and made her complexion livid.

The woman’s voice was her best feature, gentle and carefully modulated, in a low register: “I’m Mrs. Samuel Lawrence. You’re Mr. Archer, of course? You got here in no time at all.”

“The traffic’s not so bad between nine and ten.”

“Come in, Mr. Archer. Let me make you a cup of tea. I’m just having a midmorning snack myself. Since I’ve been doing all my own work, I find I need a bite between meals to sustain me.”

I stepped inside, and the screen door swung to languidly behind me. The hall was still and cool and smelt of wax. The floor was old parquetry, and its polished patterns glowed like jewels. A carpeted stairway climbed to the high dim ceiling. An ancient oak hatstand with polished brass hangers stood at the foot of the stairs. The contrast with the traffic I’d been fighting gave me a queer feeling, as if I’d stepped backward in time, or out of it entirely.

She led me to an open door at the rear. “This is my own little sitting-room, if you please. I reserve the front parlor for guests, though I must say they haven’t been using it lately. Of course it’s the off-season, I only have the three just now, my regular, and a lovely young couple from Oregon, honeymooners! If only Galley had married a man like that—but sit down, Mr. Archer.”

She pulled out a chair from the heavy refectory table in the middle of the room. It was a small room, and it was as crowded with coffee- and end-tables, chairs and hassocks and bookcases, as a second-hand furniture store. The horizontal surfaces were littered with gewgaws, shells and framed photographs, vases and pincushions and doilies. If the lady had

come down in the world, she’d brought a lot down with her. My sensation of stepping into the past was getting too strong for comfort. The half-armed chair closed on me like a hand.

I took the present by the tail and dragged it into the room: “Galley,” I said. “Is she the daughter you mentioned?”

The question struck her like an accusation, disorganizing her charm. She didn’t like the look of the present at all. She faced it when she had to, with a face clouded by bewilderment and shame. “Yes. My daughter Galatea. It’s why I phoned you, as I said.” Her gaze wandered, and lighted on the teapot that stood on the table. “You must let me pour you some tea before we get down to business. It’s freshly made.”

Her hand on the teapot was cracked and grained by dirty work, but she poured with an air. I said I took mine straight. The tea tasted like a clear dark dripping from the past. My grandmother came back with it, in crisp black funeral silks, and I looked out of the window to dispel her. I could see the Santa Monica pier from where I sat, and beyond it the sea and the sky like the two curved halves of a blue Easter egg.

“Nice view you have from here.”

She smiled over her teacup. “Yes. I bought it for the view. I shouldn’t really say I’ve bought it. It’s mortgaged, after all.”

I finished my tea and set the thin white cup in the thin white saucer. “Well, Mrs. Lawrence, let’s have it. What happened to your daughter?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “That’s what upsets me so. She simply disappeared a couple of months ago—”

“From here?”

“No, not from here. Galley hasn’t lived at home in recent years, though she always came to visit me at least once a month. She was working in Pacific Point, a special-duty

nurse in the hospital there. I always hoped for something better for Galley—my husband Dr. Lawrence was a medical man, and a very well respected one, too—but she wanted to be a nurse and she seemed to be very happy in the work—”

She was veering away from the present fact again. “When did she disappear?”

“Last December, a few days before Christmas.” This was the middle of March, which made it about three months. “Galley

always

came home for Christmas. We never failed to decorate a tree. Last Christmas for the first time I spent Christmas by myself. Even her card came a day late.” And the vague eyes swam with self-pity.

“If you’ve heard from her, I wouldn’t call it a disappearance. Can I have a look at the card?”

“Of course.” She took a black leather volume of Swedenborg out of the bookcase, opened it, and drew out a large square envelope which she handed to me as if it contained a check. “But she

has

disappeared, Mr. Archer. I haven’t seen her since early in December. None of her friends has seen her since the first of the year.”

“How old is she?”

“Twenty-four. She’ll be twenty-five next month, April the 9th, if she’s alive.” She bowed her face in her hands, having brought herself to tears.

“She’ll probably have many happy returns,” I said. “A twenty-five-year-old registered nurse can look after herself.”

“You don’t know Galley,” the damp voice said from the hidden face. “She’s always been so fascinating to men, and she’s never realized how evil men can be. I’ve tried to unknow the error, but it does no good. I keep thinking of the Black Dahlia, all the young girls that have been stolen away and destroyed by evil men.” The wide gold wedding band

on the hand over her face gleamed dully like a despairing hope.

I took out the card, which was large and expensive, decorated with a sparkling mica snow scene. Inside it said:

TO MOTHER ON CHRISTMAS DAY

Though my boat has left the harbor

In the sea of life so wide

,

I think with cheer of Mother Dear

Each joyous Christmastide

.

It was subscribed in green ink by a bold and passionate hand: “Much love, Galley.” The envelope had been mailed in San Francisco on December 24.

“Did—does your daughter have friends in San Francisco?”

“Not that I know of.” The woman showed me her face, with tear-tracks in the powder. She blew her nose discreetly in a piece of pink Kleenex. “The last few years, since she graduated, I didn’t really know her friends.”

“Do you think she’s in San Francisco?”

“I don’t know. She came back from there, you see. She didn’t come to me, but the man who runs the apartments down there, a Mr. Raisch, saw her. She had a small furnished apartment in Pacific Point, and about the end of December she turned up there and moved out, took away all her things. There was a man with her.”

“What sort of a man?”

“Mr. Raisch didn’t say. There seemed to be some kind of secret about the man—something sinister.”

“Is that a fact, or only your impression?”

“My impression. I suppose I’ve been too open to impression, lately. I can’t tell you what my life has been these last few weeks. I’ve gone down to Pacific Point on the bus half a dozen times, whenever I could get away. I’ve talked to

the nurses that knew her at the hospital. She hasn’t been near the hospital since before Christmas, when she finished her last case. It was a man named Speed who had been shot in the stomach. The police came to question him, and he nearly died. The people at the hospital seemed to think that this Speed person was a gangster. That’s one of the things that frightens me. I’ve hardly slept a wink for weeks and weeks.” There were deep bluish hollows under her eyes, pitiable and ugly in the morning light from the window.

“Actually, though,” I said, “You’ve got nothing concrete to be afraid about.”

“My only daughter is gone—”

“Girls leave home all the time. It tears the hearts out of their mothers, but they don’t know it. They don’t find out till their own kids grow up and do it to them. She probably ran off and married this man that was with her at the apartment.”

“That’s what Mr. Raisch thought. Still Galley wouldn’t marry without letting me know. Besides, I’ve checked the registrations in Pacific Point, and Los Angeles as well, and there is no record of a marriage.”