The Way Through Doors (13 page)

—And all the while, said the count, someone murmuring, Who can say therefore where a certain person is, for what is it that anchors a person? Is it their place in the story to which you are a part? Many stories hereabouts run side by side, and you cannot be at pains to unpin them, for they are sharp, and you will only sting the tips of your fingers.

Their voices grew quiet, and they lay, staring up at the icy ceiling. The count ran his fingertips along the back of her neck, and a look of helplessness came over her face.

—The empress was right about you, she said.

—No one has ever been right about you, said the count.

—Not yet, said Kolya. Not yet. But this is my debut.

The count began to say something about the events of the day, but Kolya put her hand over his mouth and stopped him.

—Today we will speak only of absurd and improbable things, things far from us.

The count nodded.

—Of absurd things, and of the

World’s Fair 7 June 1978.

An impossible date, said the count. The world will have ended long before that.

—And a good thing too, said Kolya. There is nothing so awful as a world that continues after it ought to have failed.

—I had a dream once, said the count, and as he drew in his breath to speak, it seemed the very air around him grew insubstantial, a dream in which I was visiting friends at a country estate. They were people I had never met in my true life; however, in this dream we were the best and oldest of friends. I arrived in some kind of mechanical apparatus, and was left by the gate, holding a sort of leather rucksack with my clothes and things. My friend’s wife ran down to meet me from the house. She was wearing a thin cotton dress with a flowery print. I dropped the bag and caught her up in my arms. In the dream I remembered then a past in which she and I had been lovers, long ago, when we were young, and how all that was behind us, and there would be no more of it, but that it had been a glorious thing for us both, and still was, and that she was glad that I had come, and I was glad to have come, and it felt good to lift her up and feel her body against my own. We walked up to the house, talking of nothing, of small things, really, of cats and the distance of the sun. My friend came out into the doorway, tall, strong, a man of whom one says afterwards, I wish that he were here, for our troubles could be dealt with so easily. He embraced me too, and with him there was a sudden and long past, brought up like a bucket the size of a well out of a well the size of the sea. And how we had missed each other. How so many times I had resorted to remembering things he had said or done and how that had pleased me in my time. I was welcomed into their house and our holiday began.

They lived on a sort of vineyard, and in the first days they began to teach me how one keeps a vineyard, how one cares for the grapes, how certain fields lie fallow and others bear fruit. I learned about the shade of the porch in the long afternoon, where we would sit, drinking iced drinks from tall glasses, and watching the dogs sleep and wake and sleep again.

But something began to happen. There were other people present too, people who worked at the vineyard, as well as a few servants to see to the house. There was a sort of human drama always going on, with people entering rooms and leaving them. One man would stick his head in a window, another would emerge from a cellar. People were always conversing and talking about this or that. At some point I was walking, crossing a field beside my friend. He was dressed, I recall, in a linen shirt with deep brown pants, rolled up, and bare feet. His hair was unkempt, and his eyes had that incredible quality that eyes have that are blue and also long beneath the sun.

He began to speak to me on some subject, and I responded. Someone shouted something from across the field, and then I realized what had been lurking just beyond the edges of my comprehension: the things that people were saying to one another, the way that one action blended into another, the shifting times of day, and the pleasures of companionship, but most of all the dialogue: we were in a novel. There was no other explanation. No one spoke like this in ordinary life, picking up every inch of what had been said, and delivering it back with a twist and a nuance. It had not happened just once. I felt that each remark somehow carried with it the implication of all others previous. One felt very clearly a comprehending intelligence strung through the air, setting each new moment into motion. I wrested myself out of the necessity to do and say without decision, the leash that had accompanied my passage hitherto through the book that was all about me, and a further thought occurred to me: how could a person wander into a novel? It must be a dream. Then, realizing that I was in a dream, all became possible.

I said to my friend, This is a dream. And he looked at me blankly.

—That’s ridiculous, he said. But funny. Imagine that! You, Robert, saying that this is all a dream with that dead serious expression on your face. I can’t wait to tell Isabel. She’ll laugh and laugh. Let’s go back to the house and tell her.

He pulled on my arm, touching me with that tacit permission that is between the best of friends.

I looked at him sadly. For we had had such a fine time, but now it was all over.

—Good-bye, my friend. I’ll miss you.

—I’ll see you at dinner, he said, still smiling, unbelieving, and turned away, already crossing the field.

But I, I rose up straight into the air, and saw beneath me the vineyard spread out, and beyond that, unestablished country, unestablished for I had not yet flown over it and decided in my passage what might or might not exist, creating it even as I glanced in depth upon each thing in turn.

Yes, I was flying and dreaming and shooting through the air at blinding speed. The feeling is glorious, and better than anything in this world. But at some point the dream can again take hold, and one forgets that one is dreaming. One stumbles, and again is bound to the dictates of something half created, half imagined.

—You see! he said, striking his hand upon his knee. That’s the difficulty. Things must be done easily and well or not at all. For instance, in the city even now a young man has entered the Seventh Ministry building. It is a fine and beautiful day in the fall. Fall is, of course, the best season in that city of cities.

The air is crisp and the leaves on the trees that line the streets have begun to change. As he crosses the doorstep and passes within, he sees behind the desk dear Rita the message-girl.

—Rita, he says.

—Selah! We haven’t seen you in quite some time.

—Any messages?

Rita pushes down an intercom button on her desk.

—He’s back, she says into a tiny microphone hidden in the flower vase. He looks a bit skinny, but otherwise no worse for wear.

—I was working, he replies. I heard a story, a good one: There was a municipal inspector who, on a day in October, returned to his work after some time away. He entered the building and saw his dear old friend Rita the message-girl. She was pleased very much to see him and reported his presence to the chief inspector. Afterwards, he took her hand and they did a minuet all around the room.

Rita stands, offers her hand to the young inspector. He takes it and they do a minuet all around the room. Rita is looking especially beautiful on that day, and the young inspector has the urge to kiss her. However he does not, because he likes the way things are at the ministry and does not want them to change.

Into the room then, comes the chief inspector, Levkin.

—Selah, he says. Come here. I have something to show you.

Selah goes with him, spinning Rita once more into and out of his embrace. In the next room, Levkin has set up a 16mm film projector and a screen. He goes along the windowed wall, untying the drapes. The room becomes dark.

—Sit, he says.

Selah sits down in a large leather chair, and Levkin switches on the projector. The film reel begins to turn, and light is thrown onto the screen. Numbers running, and then brilliant sunlight. A woman, regally dressed, a queen of some kind, entering a guarded room. She is extraordinarily perfect in every way, her chin, her nose, her eyes, her throat, the manner of her walking, standing, the motion of her wrists. Selah watches, hushed.

The door is opened by a guard, and the queen is admitted. In the room, seated by a small window, is a grotesque figure. A woman whose features are unpleasant, yes, difficult to look upon. The queen says to her,

—You.

The other says nothing.

—Today you are to marry the man whom I once loved. Do you know this?

Still the other says nothing.

—I am giving to you possibly the most remarkable man that was ever born and raised in this our land of Russia. He is a king among men. His tastes are the most refined tastes, his passions the most refined passions. I am giving him to you, forcing you upon him, because I know how horrible it will be for him who was once raised above all other men to taste the wares of a creature as despicable as you. What do you have to say to that?

To that, the ugly woman continues to say nothing, and the queen goes away. The light pouring through the window has the sheen of new light, of early light bred away in the east and brought here with a spring in its step. It dances through the window, coming in turn upon the face of the wretched woman and the queen, and delighting in both.

And there in the dawn, the ugly woman smiles.

—Still I will make him happy. Ugly as I am, I will please him, if he is so great a man.

The film reel blurs for a second. It is in black-and-white, and very grainy. The guard is speaking. His voice is distorted.

—There is someone to see you, Kolya.

—Thank you, she answers. I would like that.

Then a young woman enters the room, dressed in a sort of flapper outfit. She sits down beside Kolya and takes her hands into her own.

—THAT’S HER! shouts Selah and jumps to his feet. MORA KLEIN!

—I thought it might be, says Levkin quietly.

—This is how things are going to proceed, says Mora Klein to Kolya.

And bending, she whispers something into Kolya’s ear. The film ends, and behind Selah the reel flaps against the projector.

—It was her, he says again. But how?

—We are not certain, says Levkin, of whether that is: a. actual footage taken from the memory of someone who has not been delivered of the facts of their past life, b. a film shot in the 1950s, or c. a postulation on the part of a cruel and uncertain fate.

—I don’t entirely understand, says Selah. What do you mean?

—Well, says Levkin. Your girl, Mora. She might have been in the event in question. Or she may have been in the original historical occurrence. Therefore, should this prove a filmed reconstruction of the historical occurrence, they would then have had someone playing her with greater or lesser skill. Perhaps enough skill to fool you into thinking you are watching her.

—But, says Selah.

—Or, continues Levkin, she somehow managed to be present both in the historical scene and in its reconstruction and subsequent filming.

—I begin to see, says Selah. I will have to think about this.

Both men stand and look at each other in the darkened room.

—So you’ve been working on pamphlets? asks Levkin.

—I’ve finished it, says Selah.

—What have you finished?

—World’s Fair 7 June 1978.

It is my precondition, set at the start of the world.

—Very good, says Levkin. I will have to look at it. I thought, he says, that I saw someone a few days ago carrying a copy. I tried to look closer, but she noticed me watching and hurried away.

—Sif, says Selah. A girl. She came to the apartment of the pamphleteer.

—The pamphleteer? asks Levkin.

—The pamphleteer, replies Selah.

Levkin nods in a Levkin-like-Wednesday-way. Selah continues.

—Selah, she said, I want very much to read your WORLD’S FAIR and I am not about to wait any longer. She was wearing a short dress with very spectacular Roman legionnaire sandals that strap all the way up to the knee.

The pamphleteer had just come from a bath and was wearing a flannel nightshirt.

—How did you get in? he asked.

—Your keys, she said, holding them up.

—I never gave you my keys.

—But I spoke to your super and had copies made. I thought it would be prudent. I knew there would be a time when I would want to enter your apartment without your permission, and now that time has come. Give me the WORLD’S FAIR.

—But it’s not done, he said.

—It will never be done, said Sif.

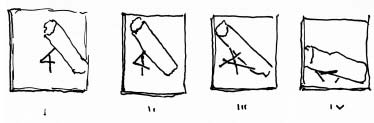

She came closer and grabbed his ear. The gesture was very rapidly done, and it flashed in the pamphleteer’s head that he would like very much to draw a schematic of the action and put it in the

World’s Fair 7 June 1978,

along with vector lines of force and angles of incidence, etc.