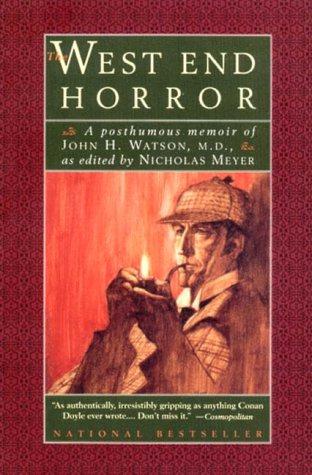

The West End Horror

Read The West End Horror Online

Authors: Nicholas Meyer

End Horror

Nicholas Meyer

E. P. DUTTON & CO., INC. / NEW YORK

The use of the character “Sherlock Holmes” and other characters created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is with the permission of Baskervilles Investment Ltd.

A condensed version of

A condensed version of

The West

End

Horror

originally appeared in

Playboy

magazine.

Copyright ©

1976

by Nicholas Meyer

All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast.

Published simultaneously in Canada by

Clarke, Irwin & Company Limited, Toronto and Vancouver

One of the interesting consequences of publishing

Tke Seven-Per-Cent Solution

has been the great number of letters

I

have received–in my capacity as editor–from all over the world. As I predicted at the time of publication, the manuscript has become the centre of a heated controversy, and people have written to me on all sorts of paper, with varying grammar, spelling, and punctuation, to tell me what they think about the book’s authenticity. (I even number among my correspondents an eleventh grader in Juneau, Alaska, who called me on the phone quite early one morning–apparently supposing Los Angeles time to be an hour

later

instead of otherwise–to tell me that he thought I was a fraud.)

A more bizarre result of the book’s appearance has been the surfacing of a number of other “missing” Watsonian manuscripts, to wit: no less than five, all submitted for my consideration as editor. They arrived from sources as diverse as their astonishing contents, from an airline pilot in Texarkana, Texas; a diplomat in the Argentine; a widow in Racine, Wisconsin; a rabbi in Switzerland (this one written in Italian!); and a retired gentleman of undefined occupation in San Glemente, California.

The manuscripts were all interesting, and all contained pedigrees, explaining their belated appearance and the circumstances under which they were composed. At least two of them–while perfectly charming–were obvious forgeries (one a pornographic put-on), a third a thinly disguised political tract, another the ravings of a disordered mind, the fourth attempt to prove Holmes’s Jewish ancestry (this was

not

from the Swiss rabbi), and one . . .

The case you are about to read is taken from a manuscript that belongs to Mrs. C. K. Verner of Racine, Wisconsin. Before it was given to me, I received the following letter from Mrs. Verner, mailed to me, care of my publishers in New York:

14, 1974

Dear Mr. Meyer:

I was really interested to read the manuscript you edited, called

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution.

My late husband, Carl,, was descended from the Vernet* (Emile Jean Horace Vernet

(1789–1863),

called Horace Vernet, famous French painter and portraitist, was the great-uncle of Sherlock Holmes.) family, which as you probably know, Sherlock Holmes was descended from, too.

I wonder if you would be interested in looking at another “long lost manuscript” of Dr. Watson’s, only this one was never exactly lost. Carl, my husband, got it from his father, who was willed it (he used to tell us) from Mr. Holmes personally.

It is hand-written and a bit difficult to read in spots, mainly because of some water damage suffered to it by Carl’s father back in the

30s

when he couldn’t afford to fix the roof of his attic.

Carl’s father (Grandpa Vemer–he died

lfl

‘46)

never let any publisher see the manuscript because it’s quite clear from the beginning of

it

that Mr. Holmes didn’t want people to read it. But there’s a lot of water under the bridge since then, and those people are all dead, anyway.

I read in the paper last week all about what they just found about Gladstone’s personal life, and I guess this can’t be any more hurtful than that.

Carl is gone since last February, and as you know, the economy is not doing too well. I’m probably going to have to sell the farm and could surely use some cash. If you want to see the papers and you are interested in them, we could come to some understanding about money. (I think I’ll take your uncle Henry’s advice, though, and try to sell the original copy! I think I read in

Time

magazine where he got a bundle on

it

from some jasper in New Mexico who collects stuff like that.)

Very truly yours,

This letter was the first of a great many which passed between Mrs. Verner and myself. On my advice, she consulted her family lawyer, and that individual proved (to my cost) to know his business. Eventually, however, matters were satisfactorily settled and I flew to Racine to pick up the manuscript after several Xeroxes had been made.

It was extremely difficult to read in places and presented very different problems from its predecessor’s.

The water damage was severe. In places words and even phrases were obliterated and impossible to decipher. I was obliged to consult specialists in this sort of thing (and I give special thanks here to Jim Forrest and the laboratories at U.C.L.A.), who worked technical wonders at bringing up missing pieces.

There were many occasions, however, when the results were unsuccessful. Here I have been forced to put in the word or phrase that seemed to fit the rest of the paragraph or page. I have done my best, but I am not Watson, and thus the reader may find a jarring note here and there. For this he must blame not the good doctor but my humble self. I thought of indicating these passages in the book but then decided such bracketing would be too intrusive. I’m sure the worst offenses will be quite obvious, anyway, and my clumsy hand will be instantly perceived.

Aside from the water damage, the most nettlesome problem was dating the manuscript. Internal evidence makes

it

quite clear that

The West End Horror

begins March

1,

1895. Ascertaining the date of its composition, however, is another matter. It was evident (to me, anyhow) that

it

was composed a lot later than

1895.

Not only does Watson refer to intervals of years between efforts on his part to get Holmes’s permission for the project, he also points out that among considerations

pro

permission were the deaths of many of the principals concerned with the case. Inasmuch as these names are not changed (impossible to disguise really, as Holmes points out), the dates are fairly easily determined. They hint at a relatively late date of composition, certainly after

1905.

The fact, however, that the manuscript is in Watson’s own hand, indicates with equal clarity that he was not yet crippled by arthritis. Beyond that,

it

is difficult to say. My own hunch–and

it

is only a hunch–is that

The West End Horror

was set down sometime after the First World War and before Holmes’s death, in

1929.

One of the things that makes me pick so late a period is that Watson–as in

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution

(but not so much)–continues to describe things that obviously aren’t there any more. That Watson never sought to recover the manuscript after Holmes’s death suggests to me that his own ailments had begun to overtake him (possibly the onslaught of crippling arthritis, which plagued his last decade)–another argument for the latish dating.

It may be noted that Watson’s use of “Americanisms” persists, and this, I feel, deserves comment. Readers skeptical of the authenticity of

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution

base part of their argument for forgery on the fact that the book contains these Americanisms, which they deem “telltale.” But they disregard two very crucial points. In the first place, Americanisms crop up all through Watson’s case histories; in the second, there is a very simple reason for this. Between 1883 and 1886, Watson was working as a physician in San Francisco, California, to pay off some of his brother’s debts. He married his first wife, Constance Adams, there, as any student of W. S. Baring-Gould’s excellent biography of Holmes and Watson* (

Sherlock Holmes of

Baker

Street: A Life of the World’s First Consulting Detective,

by William S. Baring-Gould, published by Bramhall

House,

1962.

) knows. As Holmes (after living in America for two years) remarked to Watson, in

His Last Bow,

“My well of English seems to be permanently defiled.” So much for Americanisms.

As for footnotes, I have again attempted to keep them to a minimum, though there are so many facts which check out (an argument in favor of the manuscript’s authenticity) that I felt obliged to include many of them.

Finally, a brief comment regarding the authenticity question.

We have no way of proving such things. Indeed, healthy skepticism demands that we doubt. To have discovered one missing Watsonian account might seem like a miracle; to have unearthed another smacks suspiciously of coincidence. In self-defense I point out that I cannot claim to have actually discovered either of these documents, and in the case of the second, as Mrs. Verner points out, it wasn’t exactly missing.

As regards authenticity, the reader must decide for himself, and I am aware of the controversy (am I ever!) that will surround this narrative. I conclude by referring you all to that charming poem of Vincent Starrett, which includes the wonderful words, “Only those things the heart believes are true.”

1975

“No, Watson, I’m afraid my answer must remain the same,” said Sherlock Holmes. “You’re setting down ‘the West End Horror,” he went on, chuckling at my expression. “Don’t look so astonished, my dear fellow. Your thought process was simplicity itself. I saw you at your writing table, arranging your notes. Then you came upon something you had forgotten about; it stopped you cold; you held it, read it, shaking your head with an air of familiar disbelief. Then you turned your gaze to our collection of theatrical programmes and then to my little monograph on ancient English charters. Finally, you stole a surreptitious glance in my direction as I sat absorbed in tuning my fiddle.

Voilà.”

He sighed and drew his bow across the strings in a tentative fashion, resting the end of the instrument on his knee. “I’m afraid it must still be ‘No’ ”

“But why?” I retorted with energy, not pausing to acknowledge his mental legerdemain. “Do you think I would fail to do justice to the case–or to yourself?” This last protest was tinged with irony, for his early criticisms of my efforts to keep some record of his professional activities had been harsh, indeed. They had mellowed to something less than full approval when, with the passage of time, he saw that my accounts brought him more than a modicum oF agreeable notoriety. His vanity, which was not inconsiderable, was usually flattered at the prospect.

“On the contrary. What I fear is that you

would

do justice to it.”

“I shall change the names,” I offered, beginning to see where the problem lay.

“That is precisely what you cannot do.”

“I have done so before.”

“But cannot possibly do so now. Think, Watson, think! Never have our clients been so well known! The public may argue about the true identity of the King of Bohemia*; (Long assumed by scholars to be King Edward VII. However, Michael Harrison has recently demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt that the King of Bohemia was in reality His Serene Highness Prince Alexander

(“Sandro”) of Battenberg, once king of Bulgaria.) they may guess at the real title of the Duke of Holderness. But here there could be no room for doubt–there are no fictitious characters you could substitute for those of the principals in this affair and hope to deceive your readers. To disguise them sufficiently, you would find yourself in phantasy up to the neck.”

I confessed this difficulty had not occurred to me. “Besides,” Holmes went on, “you would be obliged to recount our part in the business, as well. While scarcely unethical, it could hardly be termed legal. Destruction of a corpse without notifying the authorities is a clear violation of law and could be construed in this case as suppression of evidence.”

There the conversation ended–as it usually did–and I tucked away my notes on the entire incredible story till I should chance upon them again after another year or two and broach the subject once more.