The Willows and Beyond (4 page)

Read The Willows and Beyond Online

Authors: William Horwood,Patrick Benson,Kenneth Grahame

Tags: #Animals, #Childrens, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Fantasy, #Classics

Master Toad himself had nothing but his name, for the family fortunes in France had been lost by his late father the Count, who had been both gullible and over-optimistic in business matters, a fatal combination. Such funds as remained went the mother’s way, and since she was now re-married and living in Australia with Toad’s former butler, it was unlikely that Master Toad would gain very much financial support from her. But no matter, Toad did not care one bit, and begrudged not a single penny he lavished upon his ward, just as he never for one moment counted the cost in any of his acts of generosity to others and indulgence to himself.

Most unfortunately, Master Toad had discovered that money — Toad’s money — buys friends, or at least acquaintances, of a kind that were a generally baleful influence upon him. Yet his popularity was not due only to his wealth — indeed there were a number of fellow pupils whose paters were a good deal more wealthy than Toad, and in certain respects much better connected: namely, the sons of the High Judge (whom Toad had met occasionally in a professional capacity), the Commissioner of Police (another professional acquaintance of Toad’s) and that Bishop whom Toad had previously known as “Senior”, but who had very recently been promoted “Most Senior Bishop”.

Master Toad had had to earn the respect and loyalty of these three the hard way, and he had done so splendidly. He was better than his schoolmates at muddy games, and at avoiding those they did not wish to play, he was a good deal more imaginative in thinking up new japes and pranks, and he showed considerably more flair and courage in the execution of the same.

In some respects Master Toad became their leader, and it was undoubtedly from him that they gained the title that gave them such notoriety as a group, for they were known as the Four Musketeers. It is said that to this day that educational establishment still bears the scars of their activities.

For example: in the form of water-stains on dormitory ceilings from flooding caused by the removal of ballcocks from attic plumbing; smoke marks in two senior common rooms and the Master’s Hall from their blocking up of a suite of chimneys with a consignment of rugby balls; and, most notorious of all and a cause of a term’s rustication for each of them, the hiring of some navvies (who should have known better) to demolish a large part of that ancient wall against which the school’s most hallowed game had long been played, and the reuse of its stones, bricks, flints and cement for a soup-kitchen then being built for vagrants, waifs and strays.

It was following this incident, with which Master Toad declared himself exceptionally pleased, that all Four Musketeers descended upon Toad Hall together, and had a great deal of fun at the expense of Toad and his friends.

The issuing of free liquor to all the weasels and stoats was perhaps forgivable, as were other pranks: upon the Mole (an order for one hundred bottles of his sloe and blackberry drink, ostensibly from the most prestigious store in the Town, which had the Mole in a flap for several days); upon the Rat (a seemingly legitimate requisition by the Royal Navy of his much-loved boat for active service against the Nordic Kingdoms in retaliation for their sacking of Lindisfarne in AD 793, which caused poor Ratty considerable anguish); and upon the Badger (an apparently genuine request from the editor of that most august daily organ,

The Times,

to contribute a regular column upon country matters, the first of which he worked upon very hard indeed, only to receive a rejection slip as false and mischievous as the original request, accompanied by the comment “should try harder, or not at all”).

On the whole, the River Bank’s inhabitants were bighearted and good-humoured enough to tolerate such jokes, provided they were not too frequent, but then Master Toad and his friends went a little too far. Making mock of the adult world they were so soon to join was one thing, attempting to divert the River into the Canal quite another. They preceded this folly by sending Official Notices to all those living along its banks to expect “the River to cease its flow with effect from next Sunday, 9.00 AM prompt.” Yes, that was beyond a joke, and might have had long-lasting consequences had not the Rat and the Otter taken urgent corrective action.

A deputation led by the Badger called upon Toad and persuaded him to discipline his ward, and send his fellow pranksters packing. This he had duly done, and peace had returned to the River Bank once more (for the time being). The youth had returned to his educational establishment for the summer term, and Toad had thoughtfully arranged for him to take a Grand Tour of several European capitals in the holiday weeks thereafter, which had put the River Bank back onto an even keel for the summer months.

Now that respite was over, however, and with the final academic year before the youth was thrust out upon the world about to begin, Master Toad was expected to return to Toad Hall for some cramming in vital subjects before the new term commenced.

In all these circumstances, it is little wonder that the Rat and his friends had found Toad in such a dither of worry and concern. The Mole might very well have been annoyed with himself for not remembering about Master Toad’s return, for he had been party to its planning a month previously.

“When Master Toad goes away he always comes back changed for the worse in some way,” Toad had complained to him as they took tea together. “You see, Mole, either he won’t talk to me, or he is vain and conceited in a way that is quite unpardonable and really quite uncharacteristic of our family — I might say our noble family, which certainly has a good deal to be vain and conceited about, but normally has the politeness not to show it!”

“Yes, Toad,” said the compliant Mole, who had shared with the Badger and the others a certain amusement in watching Toad’s battles with his ward, and enjoyed the irony of watching an arch-poacher in the department of vanity and conceit struggling to turn gamekeeper.

“I don’t believe he’ll ever improve,” groaned Toad, “or show the slightest consideration for others. Now he is to be here till school starts again. What am I to do with him?”

“And yet, Toad, when it comes down to it, you do like having him about the place, don’t you?”

Toad thought for only a very few moments before, as impulsive and generous in spirit as ever, he cried, “Yes, I like him being here, I suppose — I really do! He adds life to the Hall, and has a knack of getting his way with the staff that reminds me of when I was young and without responsibility. I do not think he’s bad at heart, you know. It’s just … well, it’s that —“

“Yes, Toad?” murmured the Mole.

“O well, I shall say it: when he’s here I am miserable and when he is not here I am even more miserable. I miss him very much when he is away at school, and this summer all

I

have had from him are two postcards, from Baden-Baden and Venice respectively, depicting fat ladies and thin gentlemen uttering what he facetiously calls

double entendres,

and —“

“Two postcards are better than none, Toad,” offered the Mole truthfully — and unpaid bills from Berlin, Prague, Madrid, Cannes, Biarritz, Naples and Casablanca, the nature of the last of which gave me great cause for concern!”

The Mole had laughed gently, for if Master Toad did nothing else—though in fact he did a great deal more, and the Mole saw much in the youth that Toad ought to be thankful for — he provided them all with a good deal to think and talk about.

“O, I know he can be reasonable sometimes,” Toad had continued. “He can be lovable, he can even be thoughtful if he puts his mind to it, but what stress and heartache he causes me! I believe I have aged ten years for every year he has been with me.”

There was some truth in this, though the Mole told himself that Master Toad could hardly be blamed for that. Toad had put on a good deal of weight, and huffed and puffed more than he used to when he exerted himself, which was not often. He also had difficulty in reading small print these days and had had spectacles prescribed, which he occasionally used when he thought nobody was looking.

“We are all getting older,” said the Mole companionably And there was truth in this too, for the years had come and they had gone along the River Bank, and time had taken its toll upon them all. The Water Rat, for example, was increasingly irritable these days, especially if things were not just as he liked them, and he often seemed tired and distracted, quite worryingly so, in Mole’s opinion.

The Badger, for his part, had begun to grow deaf, and all of them had difficulty at times being understood by him, except Grandson, who lived with him now He had developed the knack of raising his voice without losing his intonation, in such a way that the Badger understood everything he said.

Nor was the Otter quite the animal he had been, for he swam more slowly than before, and his sight under water was not at all what it had been. Why, these days, Portly — now no longer quite as tubby as he had been when he gained his nickname — was better at catching fish than his own father!

Of them all perhaps the Mole seemed least affected by age, though he suffered aches and pains most mornings, and those injuries he had sustained some years previously at the jaws of the Lathbury Pike, when only his courage against that lethal foe had saved the Rat’s life, gave him trouble when atmospheric pressure rose and the wind veered to the north and turned chill.

It will all work out for the best in the end, Toad,” the Mole had said at the end of their discussion.

“I hope so,” said Toad, “but meanwhile I have arranged for a motor-car manned with some reliable former constables to meet Master Toad off the boat and ensure he comes straight home without a repetition of what happened last time.”

“You mean when he came to Toad Hall from Dover by way of a spot of motor-cycle racing on the isle of Man?”

“There will be no repeat of that kind of thing when he comes home this time!” said Toad. “None whatsoever!”

“No, Toad,” said the Mole.

“And what is more he will work at his school books in my study every day till three o’clock in the afternoon, after which I shall take him out myself for some light educational exercise and then pack him off early to bed.”

“Yes, Toad.”

So it was that in this startling way, and in a very much shorter period than it had taken the combined efforts of the Badger, Rat, Otter and Mole, working on the same project and achieving something little better than complete failure, Master Toad’s presence on the River Bank had reformed Toad into a responsible, care-worn pater, much like any other. One, indeed, no longer capable of leaping aboard his own craft and guiding them all to the Town in the wild and irresponsible way that had always been his wont; but rather, one who must stay at home and fret and worry.

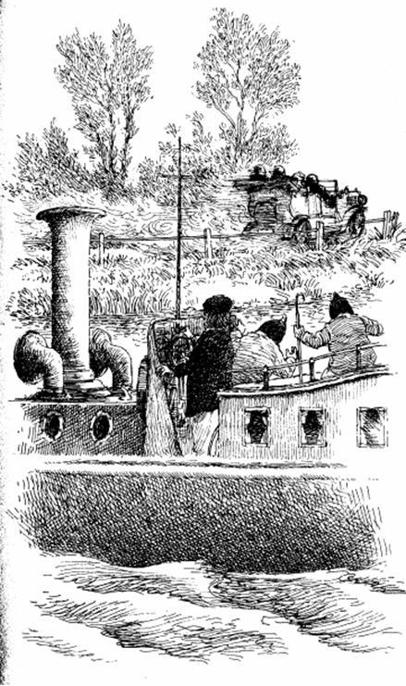

“I rather miss the old Toad,” observed the Mole that same day as he, the Rat and Nephew left Toad’s estate behind and headed towards the Town in the motor-launch.

“Do you know, old chap, now you mention it, I believe I do myself” confided the Rat. “I would rather like to see Toad getting up to his old tricks one last time!”

“Just what I was trying to say!” cried the Mole, quite forgetting that Nephew was there and ought not to hear such things. “Why, in his younger days he was capable of pranks very much worse than any Master Toad has ever got up to

—far

worse, now I come to think of it.”

“Do you remember that time he stole a motor-car?” The Rat might very well have continued with this oft-told tale, but they were at that part of the journey when the River ran quite close to the new road lately opened up between the Town and the River Bank, and his voice was suddenly drowned out by the rapid passage of a motor-car, horns blaring, accompanied by a loud, braying laughter that sounded dreadfully familiar.

“Toad?” whispered the Mole, as if he had heard a ghost.

“Toad?”

gasped the Rat, as if he had seen one.

“Master

Toad,” observed Nephew matter-of-factly, “probably.”

“But —” began the Mole, standing on tiptoe to catch a glimpse of the motor-car as it rushed by, “but Toad quite specifically arranged —“

“Think no more of it. Say nothing more of it. Do nothing about it,” said the Rat. “We are about important business and cannot, must not, be diverted from our purpose. Nephew, stop trying to see that motor-car, the road is out of view from here and it will have reached Toad Hall by now at the speed it was going! Concentrate on … drat!”

The diversion caused by Master Toad had quite distracted the normally masterful Rat, and but for Nephew’s liberal use of a boathook, and the Mole’s dabbling with an oar, they would certainly have hit the bank rather harder than they did.

“Humph!” exclaimed the Rat, getting them back on course. “No more conversation amongst the crew, if you don’t mind!”