The Wisdom of the Radish (13 page)

Read The Wisdom of the Radish Online

Authors: Lynda Browning

Our second attempt at tomato seedlings, planted a month before, had grown to only three quarters of an inch tall and only a few of them had managed to don a second set of leaves.

I tried to shrug it off. “They probably jack them up with chemical fertilizers.”

While my catty comment may have been true, it didn't negate the fact that the ability to grow tomatoes from seed was a skill. And the one thing that could replace acquired skill (besides lady luck, who had thus far spurned us) was technology. This nursery had both: it was a family operation that has been churning out seedlings for years. And the voluminous greenhouse possessed an automatic ventilation system and an automatic watering system, which meant that the temperature and moisture content of the soil were regulated without human

intervention. Even the size of the greenhouse was to its advantage: that much moist air, with the ventilation windows shut, could maintain a constant temperature through the cool nights.

intervention. Even the size of the greenhouse was to its advantage: that much moist air, with the ventilation windows shut, could maintain a constant temperature through the cool nights.

We were a bit more manual. Our advanced technology (typically preceded by, “Shit! The tomatoes!”) entailed frantically racing up the hill to yank the plastic cover off the hoophouse on a hot day, grabbing the hose, and guessing at the spray setting and length of time required to satiate the seedlings without over-saturating the soil.

“Box Car Willie,” Emmett murmured. “What a great name.”

We rooted around the platforms filled with tomato starts. Box Car Willie snuggled in flats with Radiator Charlie's Mortgage Lifter, while Pruden's Purple and Stupice bedded down on another table. Black Plum, Sun Gold, Striped German, Cherokee Purple, Sungella: we were new to the tomato world and could only guess at what sorts of fruits those mysterious names would generate. I put my money on the more creative monikersâthe Box Car Willies, Striped Germans, and Radiator Charlie's Mortgage Lifters of the world. But more important than literary sensibility was size. We were hunting for the smallest, youngest starts. We didn't want supermodels; we wanted toads. A leggy two-foot-tall tomato plant stretching out of a tiny plastic pot was distinctly inferior to a short, stocky plant. And if a seedling already had flowers, forget it. Fresh starts were best. They'd be most likely to take the transition of transplanting smoothly, and squat stalks were more able to bear the weight of mature fruit than long, thin vines.

We picked out eighty plants. As we forked over eightynine dollars and pulled the car up to the greenhouse to load up the little green things, we felt a bit silly but excited at the thought of what was to come. We thought of the heavy,

brilliantly colored fruit tucked in their rainforest of leafy vines. It was going to be one hell of a harvest.

brilliantly colored fruit tucked in their rainforest of leafy vines. It was going to be one hell of a harvest.

Â

Â

Â

Unfortunately, I enjoy the concept of tomatoes far more than the actual fruit. You simply couldn't ask for a more sensual piece of produce. Round, ripe, firm yet yieldingâsqueezing a tomato is about as close to squeezing human flesh as one can get. (For all the jokes made about melons, they're hard and unfriendly, nothing like the real thing.) And consider the color: while melons hide their brilliance inside dull rinds, tomatoes let it all hang out, lustrous and naked.

But while I'm drawn in by their soft skin and vibrant blushes, I confess that my love affair with tomatoes runs only skin deep. Because I was raised primarily on meat and carbohydrates, the textureâin particular the sliminess surrounding the seed pocketsâis a deal breaker.

I can't deny, though, that the flavor of the tomato is excellent. To enjoy the balance of sweetness and acidity without the troublesome texture, I used to partake of sauce and ketchup only. (Don't scoff: According to the USDA under Reagan, ketchup is, in fact, a fruit.) My gateway dish was the lightly broiled tomato, halved and topped with parmesan and bread crumbs; from there, I got hooked on totally raw bruschetta (with plenty of garlic, basil, and balsamic) and eased my way slowly into salted sliced tomatoes (balsamic and a fork mandatory). I still can't bite into one like an appleâeven the sweetest whole cherry tomatoes are difficult for me to pop in my mouth. But as shrimp and lobster literally induce my gag reflex, I readily admit that my palate is handicapped.

In all fairness to the tomato, my culinary caprice doesn't deserve any historical support. And yet a cautionary attitude toward the fruit does have precedentâplenty of precedent. In 1820, the legend goes, a man named Colonel Robert Gibbon Johnson made a brave announcement: at high noon on September 26 he would stand in front of the Boston courthouse and

eat an entire bushel of tomatoes

. People gathered outside the courthouse to watch the spectacle, awaiting the silly sop's imminent death. After all, this man was about to consume not one but twenty or so of the poisonous fruits. The townspeople were shockedâand, let's face it, gravely disappointedâwhen Colonel Johnson lived to tell the tale.

eat an entire bushel of tomatoes

. People gathered outside the courthouse to watch the spectacle, awaiting the silly sop's imminent death. After all, this man was about to consume not one but twenty or so of the poisonous fruits. The townspeople were shockedâand, let's face it, gravely disappointedâwhen Colonel Johnson lived to tell the tale.

A family of five in Hawking County, Tennessee, wasn't so lucky. On an ordinary day in 1963, the Mason family

g

settled down for a midday dinner of split pea soup, pasta with meat sauce, and the season's first sliced tomato. According to firsthand accounts, minutes after three of the family members sampled the tomato, they found themselves staggering across the roomâwhich had, oddly enough, begun to ebb and flow around themâhit by waves of nausea. The son drove them to the hospital. There, the father swatted imaginary swarms of insects while the mother battled violent, whole-body convulsions, and all three suffered dry mouth and dilated pupilsâall from a single slice of a seemingly innocent fruit.

30

g

settled down for a midday dinner of split pea soup, pasta with meat sauce, and the season's first sliced tomato. According to firsthand accounts, minutes after three of the family members sampled the tomato, they found themselves staggering across the roomâwhich had, oddly enough, begun to ebb and flow around themâhit by waves of nausea. The son drove them to the hospital. There, the father swatted imaginary swarms of insects while the mother battled violent, whole-body convulsions, and all three suffered dry mouth and dilated pupilsâall from a single slice of a seemingly innocent fruit.

30

Of course, the tomato's history didn't commence in 1820, and the legend of its toxicity goes back hundreds of years before Colonel Johnson allegedly rendered a not-guilty verdict with his compelling argument at the Boston courthouse. Like Paddington Bear, tomatoes originated in darkest Peru. Wild tomatoesâof which ten surviving species have been

identified by botanistsâpopulated the Andean highlands. Sporting small yellow flowers that matured into small yellow fruit, ancestral tomatoes bear little resemblance to today's multicolored behemoths.

identified by botanistsâpopulated the Andean highlands. Sporting small yellow flowers that matured into small yellow fruit, ancestral tomatoes bear little resemblance to today's multicolored behemoths.

From Peru the tomato apparently made its wayâhow, we don't entirely knowâto Central America. There the Aztecs dubbed it

xitomatl

(“plump thing with a navel”) and did something brilliant: they combined the proto-tomato with peppers and corn to make the world's first salsa, a culinary achievement not to be taken lightly.

xitomatl

(“plump thing with a navel”) and did something brilliant: they combined the proto-tomato with peppers and corn to make the world's first salsa, a culinary achievement not to be taken lightly.

From there, the saga of xitomatl is just too entertaining to pass up. Spanish explorers, in the process of annihilating Central American Aztecs, picked up a few xitomatl and brought them back to Europe. Some historians believe they came with Cortez after he took over Tenochtitlan (present day Mexico City) in 1521. Others point to Christopher Columbus for his obvious schoolchild cachet. But as is the case with most of our history, no one really knows how precisely it happened; we just know that tomatoes somehow made their way to Europe. More precisely, we know that the first documented record of the tomato was penned in 1544 by an Italian physician/botanist elegantly named Pietro Andrea Mattioli. You can almost hear the word “tomato” in his name, can't you? And yet Pietro Mattioli renamed the “plump thing with a navel” the “golden apple,” or

pomi d'oro

. This later became simply

pomodoro

, the modern Italian word for tomato.

pomi d'oro

. This later became simply

pomodoro

, the modern Italian word for tomato.

Although the name may sound like a shining endorsement, it also possesses undertones of Eden's dangerous fruit. Mattioli correctly classified the tomato as belonging to the nightshade family, and because other members of the nightshade family were known to induce hallucination and death when ingested, many folks were understandably skeptical about

biting into the newfangled golden apple. Mind you, these same people were willing to drip nightshade poison into the sensitive mucous membranes of their own eyes. The tomato's close cousin, belladonnaâliterally translated as “pretty woman”âwas so named because elegant ladies would squirt it in their eyes to induce pupil dilation (an act that belongs in encyclopedias next to foot binding and five-inch stilettos, under Things We Shouldn't Do to Our Bodies to Look Sexy).

biting into the newfangled golden apple. Mind you, these same people were willing to drip nightshade poison into the sensitive mucous membranes of their own eyes. The tomato's close cousin, belladonnaâliterally translated as “pretty woman”âwas so named because elegant ladies would squirt it in their eyes to induce pupil dilation (an act that belongs in encyclopedias next to foot binding and five-inch stilettos, under Things We Shouldn't Do to Our Bodies to Look Sexy).

Alas, the Italians got off to a rocky start with the fruit that would eventually become a focal point of their national cuisine. Meanwhile, the French found themselves romanced by the tomato's latent sensuality. Poison?

Non, mes amis, c'est la pomme d'amour.

Nightshade be damned: in France, the tomato became known as the love apple, an aphrodisiac that was especially palatable when paired with butter, cream, a hearty cheese, wine, and crusty breadâand for all that, it remained remarkably friendly to the figure.

Non, mes amis, c'est la pomme d'amour.

Nightshade be damned: in France, the tomato became known as the love apple, an aphrodisiac that was especially palatable when paired with butter, cream, a hearty cheese, wine, and crusty breadâand for all that, it remained remarkably friendly to the figure.

Despite French passion for the fruit, the tomato's reputation continued to suffer. In the 1700s it was dealt a severe blow by Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus. Nightshade hallucinations often involve a feeling of flying, so nightshade was popularly associated with witchcraft; in German folklore, witches used nightshade as a lure for werewolves. This history clearly factored into Linnaeus' scientific name for the tomato:

Solanum lycopersicum

. Leave it to a Northern European to take “plump thing with a navel”âalso known as “golden/love apple”âand turn it into “quieting wolf-peach.” Scottish botanist Philip Miller later upgraded the tomato to

Lycopersicon esculentum

or “edible wolf-peach.”

Solanum lycopersicum

. Leave it to a Northern European to take “plump thing with a navel”âalso known as “golden/love apple”âand turn it into “quieting wolf-peach.” Scottish botanist Philip Miller later upgraded the tomato to

Lycopersicon esculentum

or “edible wolf-peach.”

Which brings us back to the question of poison. Why weren't the tomatoes consumed by the Mason family in 1963 edible? As it turned out, the family's green-thumb son

had grafted a tomato vine onto jimson weed, a hardy, frost-tolerant close cousin of the tomato. On the surface, the idea was brilliantâand, in fact, it's the same concept that lies behind all commercial fruit production today. Take a delicious, but perhaps less-than-vigorous, fruiting plant and stick it onto the most vigorous root stock you can find. With a bit of luck, you'll end up with healthier plants, consistent production in a variety of environments, and more fruit.

had grafted a tomato vine onto jimson weed, a hardy, frost-tolerant close cousin of the tomato. On the surface, the idea was brilliantâand, in fact, it's the same concept that lies behind all commercial fruit production today. Take a delicious, but perhaps less-than-vigorous, fruiting plant and stick it onto the most vigorous root stock you can find. With a bit of luck, you'll end up with healthier plants, consistent production in a variety of environments, and more fruit.

The Masons' grafting experiment didn't go quite so smoothly. The graft took, and soon jimson tomatoes were flourishing in the Masons' backyard. But when the family sat down to taste their first slice of homegrown summer, they learned the hard way that not all plant varieties are suitable as rootstocksâand that, in fact, we're very lucky to be able to eat tomatoes at all.

The leaves of the tomato plant are toxic if ingested. However, unlike jimson weed, they do not produce toxins that are carried up to and concentrated within the fruit. (Word to the wise: If your goal is to produce a healthful, edible fruit, don't graft anything onto a plant that has a habit of concentrating poison in fruit.)

Today, Americans spend more than four billion dollars

31

on more than 160 varieties of perfectly edible golden apples. Thanks to intrepid tomato eaters like Colonel Johnson and Thomas Jefferson (who also reputedly ate a tomato in public to prove it wasn't poisonous), by the 1800s the tomato was not only accepted in America, it was turning into an industry. Seed catalogue sales soared. Farmers developed varieties suited to their regional growing conditions and tastes. The tomato became what it is today: a food fit for everyday sandwiches, soups, sauces, casserolesâpretty much anything, in fact, except dessert.

31

on more than 160 varieties of perfectly edible golden apples. Thanks to intrepid tomato eaters like Colonel Johnson and Thomas Jefferson (who also reputedly ate a tomato in public to prove it wasn't poisonous), by the 1800s the tomato was not only accepted in America, it was turning into an industry. Seed catalogue sales soared. Farmers developed varieties suited to their regional growing conditions and tastes. The tomato became what it is today: a food fit for everyday sandwiches, soups, sauces, casserolesâpretty much anything, in fact, except dessert.

Would that the history of the tomato concluded there and xitomatl fruited happily ever after. But the tomatoâsweet/ succulent, toxic/healthfulâcontinues its series of identity crises. In the United States, different legislative bodies have, at different times, declared the tomato to be a vegetable, a fruit, or both. In 1883 the Supreme Court determined it to be a vegetable. Yes, that's right: not only did the highest court in the land debate what food group the tomato belongs in, they also got it wrong. Despite the existence of botany and taxonomy, both well-developed disciplines in the late 1800s, the Court decided that the culinary uses of the tomato (for use with a main dish rather than a dessert) rendered it a vegetable for tariff purposesâa designation that continues to this day.

Meanwhile, botanists, biologists, and anyone who has passed a reasonably robust biology course would argue that a tomato is undeniably a fruit. It's not the round sensuality of the thing that renders it a fruit, but the actual act of flower sex. The male stamen fertilizes the female pistilâtomatoes are self-pollinating, so this process takes place entirely within a single flower, triggered by the vibration of a breeze or a bee's wingsâand produces fertile seeds encased in a nutritious body that provides a dispersal mechanism for the seeds. In short, fruit. (Note that eggplants, cucumbers, and squash share this scientific definition despite vegetative culinary use, but no one cares enough about them to fight about it.)

And so we return to the tomato plantâfruit, vegetable, deadly, and deliciousâand the process of growing it.

Â

Â

Â

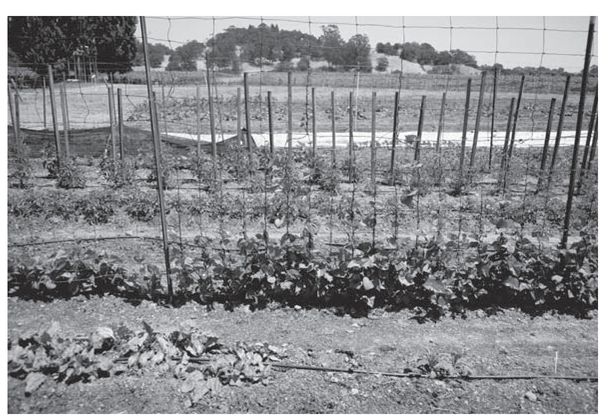

In short order, we unloaded eighty seedlings from the station wagon and set them down on the field. They'd spend

two nights adjusting to life outside the comforts of the greenhouseâ“hardening off” in farmer-speakâbefore being transplanted into two long rows.

two nights adjusting to life outside the comforts of the greenhouseâ“hardening off” in farmer-speakâbefore being transplanted into two long rows.

Other books

Edge of Glory (Friendship, Texas Book 1) by Magan Vernon

Never Steal a Cockatiel (Leigh Koslow Mystery Series Book 9) by Edie Claire

Miles by Carriere, Adam Henry

The Human Age by Diane Ackerman

Burned by Nikki Duncan

Finger Prints by Barbara Delinsky

Waiting for Rain by Susan Mac Nicol

Lawful Wife (Eternal Bachelors Club) by Tina Folsom

Why It's Still Kicking Off Everywhere by Paul Mason

Twilight's Encore by Jacquie Biggar