The Wisdom of the Radish (17 page)

Read The Wisdom of the Radish Online

Authors: Lynda Browning

All creaturesâplant, animal, or otherwiseârequire nitrogen. Nitrogen compounds form the basis of proteins and nucleic acids, the very building blocks of life and reproduction. The air we breathe is 78 percent nitrogen, so you'd think we earthlings would have it pretty good. But that massive reservoir of gaseous N

2

is inaccessible to the likes of you and me. We can uptake our nitrogen only from plants or from animals that have dined on plants. And plants, in order to process nitrogen, need it to be “fixed” firstâthat is, made into a bioavailable compound (one that contains either oxygen or hydrogen).

2

is inaccessible to the likes of you and me. We can uptake our nitrogen only from plants or from animals that have dined on plants. And plants, in order to process nitrogen, need it to be “fixed” firstâthat is, made into a bioavailable compound (one that contains either oxygen or hydrogen).

Which is where legumes come in. As a legume grows, its roots are invaded by

Rhizobium

, a commonly occurring soil bacterium. Once established,

Rhizobium

multiplies like mad, forming bumpy nodules on the fibrous rootsâa most

welcome disease. The plant encourages

Rhizobium

by supplying it with energy and nutrients;

Rhizobium

responds in kind, bequeathing the plant with ammonium, a bioavailable form of nitrogen.

j

Thus, because they've got their own portable fertilizer, legumes have the handy-dandy ability to colonize nitrogen-poor soils. When the legume dies and decomposes, nitrogen is re-released into the soilâproviding a friendlier sprouting environment for future plant inhabitants.

Rhizobium

, a commonly occurring soil bacterium. Once established,

Rhizobium

multiplies like mad, forming bumpy nodules on the fibrous rootsâa most

welcome disease. The plant encourages

Rhizobium

by supplying it with energy and nutrients;

Rhizobium

responds in kind, bequeathing the plant with ammonium, a bioavailable form of nitrogen.

j

Thus, because they've got their own portable fertilizer, legumes have the handy-dandy ability to colonize nitrogen-poor soils. When the legume dies and decomposes, nitrogen is re-released into the soilâproviding a friendlier sprouting environment for future plant inhabitants.

Because of its special

Rhizobium

relationship, gardeners use members of the Fabacaea family as a winter cover crop, plowing them under in spring to add nitrogen to the soil. Or, if they're rotating crops in succession, farmers will plant beans after a heavy feeder like corn because beans will produce amply even in nitrogen-depleted soil.

Rhizobium

relationship, gardeners use members of the Fabacaea family as a winter cover crop, plowing them under in spring to add nitrogen to the soil. Or, if they're rotating crops in succession, farmers will plant beans after a heavy feeder like corn because beans will produce amply even in nitrogen-depleted soil.

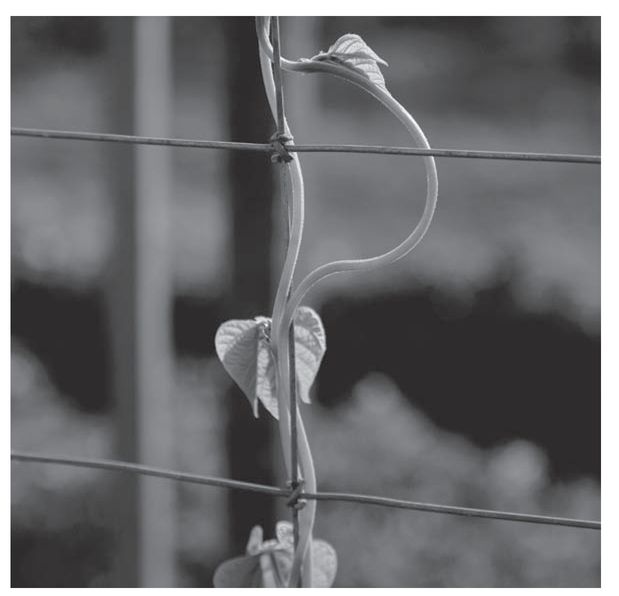

And the legume is as beautiful as it is useful. The pole bean rears his little headâseed-noggin, leaf-earsâout of the crusty clay soil and instantly demands attention. This is a bold seedling, tall and sturdy, yet the youngster politely tucks his leaves down at night and raises them to greet each morning with a fine sun salutation. As he grows, he inscribes patterns against the blue sky, twining irregularly around whatever happens to be in his path, leaving loud cursive loops leading to the runner's final serif.

There's something a bit dark about the legume, tooâespecially in the context of an entire row of beans. They clamber up each other, grappling desperately for light, using other things to support themselves rather than developing a strong enough stem on their own. But if it's dark it's also beautiful: the evolutionary efficiency, the speed of growth, the brilliance of the bean's swaying dance that leads it to twine around

objects. A marvelous adaptationâlike the strangler fig, gorgeously sinister.

objects. A marvelous adaptationâlike the strangler fig, gorgeously sinister.

And, like a peasant, the bean seedling needs no coddling. He's tender, perhaps, but he's born with an ability to function. If cucumber beetles attack his first two leaves, he has energy enough to put out two moreâand another, and another, until the bugs can't possibly keep up. By comparison, the tinier seeds of the plant worldâonions, carrotsâemerge more like marsupials. They're so fragile that they must be pampered, endlessly weeded and watered. The bean? He's grateful if you pull out the weeds, but he'll outgrow them even if you don't.

Which is why “full of beans” is appropriate. The phrase originally referred to someone who, like a manly peasant worker, brims with energy. Of all the clichés, this one fits the plant best.

Â

Â

Â

At the moment, I was very full of beans. In fact, I was a little past fullâand despite my proud smiles at the farmers' market, back at the field my enthusiasm for the prolific legume was running on empty.

As usual, I'd been the original enthusiast for the too-bigfor-our-britches endeavor. I insisted that we plant five different heirloom varieties of beans, urging at least one hundred row-feet of the crop. When we experienced a near-perfect germination rate, I airily dismissed the concept of thinning the seedlings. Each one was so valiant, so artisticâhow could we possibly get rid of any?

And so I was the only one to blame when the plants that started out so lithe and graceful rapidly grew into an insurmountable thicket.

At first, I was a little bit proud of my bean jungle. It was magnificent, a peasant hedge fit for a king: ten feet tall, three feet deep, and practically impenetrable to light. Unfortunately it blocked the tomatoes' afternoon sun. I reasoned that the loss of ripe tomatoes would be offset by a plenitude of beans. After all, beans and tomatoes sell for approximately the same price per poundâno harm done.

That sort of reasoning predated the Great Bean Revelation.

The revelation took place on a Friday, our first real bean harvest, at the time when miracles happen on farmsâwhen the farmer stops hoeing, sowing, and weeding, and instead devotes his waking hours to reaping. Zucchini can't be contained. Cherry tomatoes ripen at breakneck speed, the heirlooms are swelling and yellowing, crookneck squash form a snake's nest, and if the Armenian cucumbers aren't harvested every other day, there's going to be hell to pay.

And on this Friday, in the midst of a veritable harvest festival, Emmett and I turned our attention to the bean thicket. Eying our tall, dark nemesis, we each grabbed a bin and headed to the shady side of the row. The lush bean vines protected us from the sunâbut the lush bean vines also hid the bean pods inside their green folds. Picking beans is an intimate endeavor and the plant seems to like the attention. Its furred leaves cling to clothing, leaving farmers festooned with green spades.

An hour later, sticky with sweat, I stepped back to see what we'd accomplished. Between the two of us, we had managed to (mostly) harvest (a bit less than) one half of one row. There were three rows. We had harvested probably a thousand beansâwhich added up to a mere bin.

At this point, I was sweaty, tired, and humbled by the bean. What a bounty of food, what a phenomenal ability to proliferate one's offspring. For each bean pod we picked

would, if we'd let them develop further, produce several bean seeds capable of creating new plants. If each plant produced one hundred pods (a conservative estimate), that would easily be five hundred potential progeny.

would, if we'd let them develop further, produce several bean seeds capable of creating new plants. If each plant produced one hundred pods (a conservative estimate), that would easily be five hundred potential progeny.

The bean tendrils meandered as they reached for the sky.

And so my awe came with a healthy dollop of fear.

Here's the thing: it takes one good tomato to add up to a pound. The harvesting effort required is at most thirty seconds to locate the tomato, snip it off, and place it in the box. In contrast, a person must pick close to one hundred beans to add up to one pound. Instead of thirty seconds of work, it's more like ten minutes.

And so I began to resent the beans.

Especially

for shading out the tomato plants. Emmett resented them because they gave him a rash. He lay in bed at night, scratching his hands, forearms, biceps, the back of his neckâresenting

me

because I hadn't permitted the bean thinning, a move that would have diminished rash potential. And pretty soon, we both resented the fact that in order to stay on top of the beans, we had to harvest them for several hours every day. In August, which in Sonoma County means hundred-degree weather. While the cucumbers could, in a pinch, be kept at bay with a twice- or thrice-weekly harvest, the beans wouldn't wait that long. I'd blink and suddenly my tender Dow Purple Pod pole beans would be grossly elongated and podded out, suitable only to shuck for soup beans.

Especially

for shading out the tomato plants. Emmett resented them because they gave him a rash. He lay in bed at night, scratching his hands, forearms, biceps, the back of his neckâresenting

me

because I hadn't permitted the bean thinning, a move that would have diminished rash potential. And pretty soon, we both resented the fact that in order to stay on top of the beans, we had to harvest them for several hours every day. In August, which in Sonoma County means hundred-degree weather. While the cucumbers could, in a pinch, be kept at bay with a twice- or thrice-weekly harvest, the beans wouldn't wait that long. I'd blink and suddenly my tender Dow Purple Pod pole beans would be grossly elongated and podded out, suitable only to shuck for soup beans.

This was a conundrum we hadn't anticipated back when we were killing hundreds of seedlings and wondering whether we had enough produce to take to market. Too much produce? The thought was absurd. But as economists and food system analysts love to say, there is no food shortage on this planetâthere's just a distribution problem. Globally, 4.3 pounds of food are produced for every man, woman, and child per day: more than enough to satisfy everyone.

36

36

Still, I assumed that the distribution problem took place elsewhere. It was global. America had too much, Africa too little. And if we

were

considering a national scale, surely the distribution gap took place in the massive, subsidized cornfields of the Midwestânot on a tiny, two-acre Californian farm run by two novice farmers who only recently learned the proper way to plant a potato.

were

considering a national scale, surely the distribution gap took place in the massive, subsidized cornfields of the Midwestânot on a tiny, two-acre Californian farm run by two novice farmers who only recently learned the proper way to plant a potato.

And yet Foggy River Farm had become part of the economists' scenario. It wasn't just the beans, eitherâit was

everything. Our little postage stamp was bursting at the seams. We couldn't sell all the produce, let alone eat it.

everything. Our little postage stamp was bursting at the seams. We couldn't sell all the produce, let alone eat it.

Our initial solution had been the local food pantry. They gladly accepted our cucumbers, beans, and summer squash, but drew the line at chard and kale. Not a popularity contest, mind youâalthough chard and kale would lose that handilyâit was just that they didn't have sufficient refrigerator capacity, so they only accepted produce that would be okay for twenty-four hours or so unrefrigerated. But the food pantry wasn't open on the weekends, when it would be convenient to stop by on the way home from the farmers' market. We had to deliver on Mondays, which were one of our busiest field days (since we'd spent our weekend at the farmers' markets, mostly away from the field). And, all do-gooder, warm feelings aside, the stress of constantly harvesting and driving to the edge of town to give away the produce that we were trying to make a living from was starting to take its toll on us.

In the beginning, I was as excited as the pastor who received our several pounds of heirloom beans at the Food Pantry every Monday. On weekday mornings, I'd pick the west side of the pole bean rows, marveling at the productivity of the different varieties: Kentucky Wonders, Blue Lakes, and Dow Purple Pod pole beans, the earliest and biggest producer of all. I'd crouch down to pluck the pods of the bush beansâyellow wax, pale and tender, Royal Burgundy, curved and dark. In the afternoons, Emmett and I would patrol the east side of the bean rows, hiding always from the onslaught of the sun.

Morning beans, afternoon beansâand beans featured prominently at dinnertime, too. In those early days, I couldn't contain my delight at their flavor, sautéed with a bit of olive oil and garlic, seasoned with sea salt and black pepper and

perhaps a splash of balsalmic vinegar or the squeeze of a Meyer lemon, just at the end.

perhaps a splash of balsalmic vinegar or the squeeze of a Meyer lemon, just at the end.

But the bounty was quickly turning into an all-out produce profusion. And while we did have a few too many cucumbers, crookneck squash, and chard leaves, our angst centered around the beans. The once-treasured beans, the once-poeticized beans, the once shake-your-moneymaker gourmet beans now engendered a certain level of vitriol in our hearts.

Emmett, unfortunately, had been cast in the role of Enforcerâthe person who, day after day, reminded me that it was once again time to pick the beans. This left me to play the Dennis the Menace, “A w w w , shucks, not again” character. When bribing didn't work (“Hey mister, want some gelato?”), I dragged my feet like a petulant preschooler all the way to the field.

Emmett began, “Really, when it comes to the beans, I'm just about ready to ...”

I jumped in: “Rip them all out and burn them?”

Â

Â

Â

To be fair, the beans did not entirely choke out our heirloom tomato harvest. They merely slowed it down. In mid-August, as the first of our heirloom tomatoes readied themselves, we harvested the ripest ones the evening before market and arranged them carefully in cardboard fruit boxes we'd picked up at a local grocery store. Compared to bean harvesting, tomato picking was a breezeâthe fruit piled up quickly. Unlike beans, however, it required a deft touch.

Our heirloom tomatoes were staked, tied onto wooden poles with lengths of stretchy green plastic. And here's the thing about heirlooms: if they're not diseased, split, moldy,

stunted, punctured, sun scalded, infested by ants, or prematurely gnawed by overeager deer/rodents/teenagers, then chances are they're stuck between the vine and the stake. The biggest, most beautiful ones are of course the most likely to be inextricable, which means that after several frustrating minutes of trying to gently pull them out from every possible angle, you will inevitably go for the big yank technique, impaling the most beautiful tomato in the world on its own vine. Of course, the moment the tomato has been mortally punctured, the offending vine will once again seem soft and pliable, and you'll never quite figure out exactly what part of the vine inflicted the woundâa mystery no doubt related to its nightshade witchcraft roots. Edible wolf-peach, indeed.

stunted, punctured, sun scalded, infested by ants, or prematurely gnawed by overeager deer/rodents/teenagers, then chances are they're stuck between the vine and the stake. The biggest, most beautiful ones are of course the most likely to be inextricable, which means that after several frustrating minutes of trying to gently pull them out from every possible angle, you will inevitably go for the big yank technique, impaling the most beautiful tomato in the world on its own vine. Of course, the moment the tomato has been mortally punctured, the offending vine will once again seem soft and pliable, and you'll never quite figure out exactly what part of the vine inflicted the woundâa mystery no doubt related to its nightshade witchcraft roots. Edible wolf-peach, indeed.

In my sweaty hand was a fatally wounded Cherokee Purple.

Damn

, I thought, and then,

More bruschetta for us

.

Damn

, I thought, and then,

More bruschetta for us

.

As Emmett and I filled the fruit boxes, they transformed from a drab cardboard backdrop to a lively mosaic of red, purple, orange, yellow, and green. It was spectacular, this splash of summer, and the sheer number of plants meant that our failures were not nearly as important as they would have been if we were only tending a few bushes in the backyard. We could take a hit, lose five plants, pass over the sunburned, wormy fruits, suffer through the shade of the bean trees, and still bring three cardboard boxes full of plump fruit to the farmers' market.

Other books

Break Point by Kate Rigby

Formidable: Shifters Forever Worlds (Ever After Dark Book 1) by Elle Thorne

Somewhere in Between by Lynnette Brisia

Rogue Soldier by Dana Marton

Cyclops One by Jim DeFelice

The Seduction Vow by Bonnie Dee

Brianna's Navy SEAL by Natalie Damschroder

The Monk and the Riddle: The Art of Creating a Life While Making a Living by Komisar, Randy, Lineback, Kent

The Secret Trinity: Reign (Fae-Witch Trilogy, Book 3) by Bernel, Jenna

Blood Revealed by Tracy Cooper-Posey