The Witling (16 page)

The light dawned on Bjault. He glanced across the deck at Yoninne, but that worthy stared grimly at the shoreline, determined to ignore them.

Well

, Bjault sighed to himself,

I suppose neither of us were meant to be intriguers.

He was almost relieved that the boy understood the situation. Aloud, he said, “There are many things we don’t know, Your Highness. Perhaps that’s why we … tricked you. If you were lost hundreds of leagues from home and surrounded by strangers who might be hostile, wouldn’t you act a little bit, uh, sneaky—even toward the people you thought were friendly?”

The prince’s gaze fell back to the fire shining through the isinglass grating of the stove. “I suppose. From you I could accept this, but I thought Io—” He broke off, started on an entirely new course. “The boat you saw roll over was preparing to jump to some road in the southern hemisphere.”

It was an ironic fact that in some situations the Azhiri could jump thousands of kilometers easier than hundreds: for if your destination lay due south as far below the equator as you were above it, then you could teleport there without suffering even the smallest jolt. So the Snowkingdom could occupy opposite ends of the world, yet—in a sense—still be a single, connected domain.

But that didn’t really answer Bjault’s question. “I mean, why do they turn the boat upside down?”

Pelio shrugged again. “The people at the South Pole are standing on their heads compared to us and no one can reng a boat unless it’s first turned so the keel will point down at the destination. That’s true even for the jumps we’ve been making, though you probably haven’t noticed the trim changes, they were so slight.”

This sounded like nonsense, till Ajão saw that it could follow from conservation of energy: if no adjustments were necessary, you might make a perpetual-motion machine by teleporting a pendulum back and forth between the North and South poles. An interesting and curious fact—but now he could think of nothing more to ask. And it seemed that Pelio had nothing more to say. Despite all the men on the deck, the boy was completely, miserably alone. Ajão sighed and returned to his seat.

Their arrival at the North Pole was unexpected and abrupt. Suddenly they were floating in a new lake, several times larger than previous ones. The traffic was heavy here—as if this lake were the juncture of many routes. Ice-block warehouses stood all around the water, many connected by hallways whose roofs barely poked above the dustlike snow that blew across the water from the plain beyond. If those dumpy buildings were the palace they’d been hearing about, then this was quite an anticlimax.

But Pelio pointed at the horizon. In the middle distance Ajão saw a collection of low domes and stubby towers, all gleaming silver-blue in the moonlight. Here and there, tiny holes broke the smooth curves. At Ajão’s gentle but persistent prodding, Pelio explained: “Those are windows; the watchtowers are two hundred feet tall. In a way, the Snowfolk palace is even more secure than my father’s Keep. At both poles the palace is surrounded by hundreds of miles of ice. Any pilgrims who make it this far would be seen from those towers long before they get to the palace.”

Sixty meters high,

thought Bjault in amazement; the figure put the palace in a new perspective. Someone must know some statics to build with ice on that scale. The palace was in a class apart from the shabby snow huts they had seen along the road.

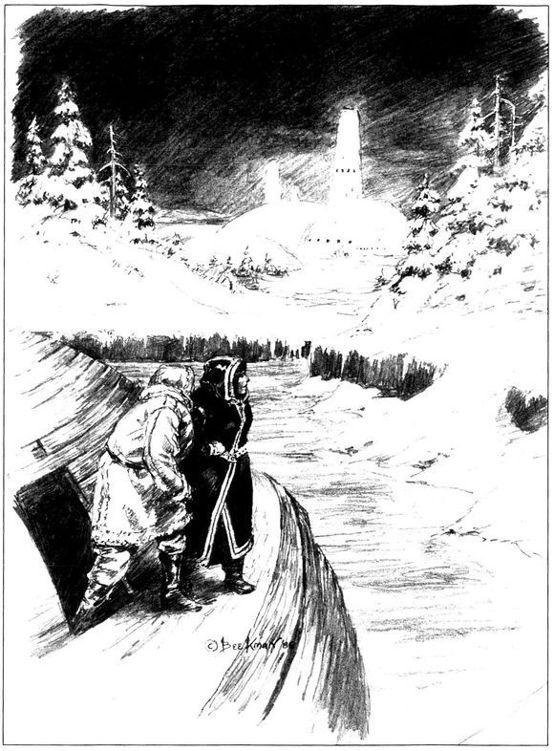

Their Snowman pilot forced open a hatch and leaned out to shout through the wind at the masked and muffled figures on the wharf below. The two on the wharf listened a moment, then waved and trudged slowly back to their shelter. The pilot shut the hatch and the torrent of frigid air sweeping the deck became a mere breezy draft.

“We’re getting permission to enter the transit lake within the palace,” said Pelio. “It will be easier to check the hull and clean the windows in there … . This is more courtesy than I had expected.”

Twin yellow lights glowed from one of the dark holes in a palace tower. The pilot looked at the lights, nodded, and sat down. For just a moment he concentrated on this last jump, and then they were within the Snowpalace. The vast room would have been completely dark but for the blades of moonlight that speared down through slits in the dome above them. They were floating in a pool some fifty meters across. Just beyond the water, a ring of pillars—each as wide as the pool itself—tapered up toward the roof. Yet for all their apparent strength, those columns stood translucent in the pale moonlight, their knifelike corners transparent. Several crewmen eased open the main hatch, and now Ajão could see that the floor beyond the pool was littered with ice or snow—a strange messiness, considering the geometric perfection of everything else. But the air coming through the hatchway was warmer than outside the palace, and—most important—there was no wind.

Then the men by the opening slid slowly to their knees, and fell onto the outer deck. Pelio stood up, started toward the fallen men, but the chief navigator waved the witlings back as he and his crew ran toward the still figures. Bjault felt Leg-Wot’s hand close painfully around his elbow, heard her whisper, “Gas!” in Homespeech. And the moment she said it, he knew she must be right. He had participated in enough space-emergency drills to recognize this type of casualty.

By now, most of the crew were clustered around the fallen men. “Do you suppose they were kenged, Captain?” one of them shouted at the chief navigator.

The navigator shook his head angrily. “You didn’t sense an attack, did you? Besides, the Snowman’s down, too.” And as he spoke his knees gave way and he pitched heavily forward, across the other bodies. Around him there were cries of terror, quickly turning into choking sounds as the others collapsed. The two Novamerikans held their breath as the crewmen fell, first the ones by the door and then those further and further away. Finally, only Leg-Wot and Bjault were left standing. They stared silently, helplessly at each other. They knew what was happening, but there was nothing they could do about it.

At last Ajão had to inhale. He smelled nothing—no corrosive taint, anyway. But suddenly he was on his knees, and reality was slipping away. Somewhere far away, he heard Leg-Wot swearing to herself, as she, too, accepted the inevitable.

D

aylight. It was the first thing Leg-Wot sensed as she struggled back toward consciousness: a cheerful yellow glow that penetrated her eyelids and made her think of spring mornings on Homeworld. But her fingers were numb and her back cramped with cold. Where was she? Her eyes opened and she stared up into the sparkling glints of sunlight coming off the icy pillars and roof above her—the Snowpalace! They were still trapped in the Snowpalace. Only now the sun was up, high enough in the sky so that its light fell directly on the glazed floor, and glittered off the edges and facets of the dome’s supporting pillars. But this was impossible! The sun wouldn’t rise over the Snowpalace till spring.

Someone groaned nearby. Yoninne forced herself to a sitting position and looked across the heap of dyed animal furs she sat upon. There were Pelio and Bjault. Pelio looked as though he had been awake for several minutes. Yoninne turned quickly away from him. It was Ajão who had groaned: he was just coming to. She crawled across the furs to him.

“The light. Where did all the light come from?” she asked.

Pelio pursed his lips but said nothing. Bjault spoke weakly, “Looks as though they’ve jumped us to the South Pole.”

They

? Leg-Wot turned to follow his gaze. “They” were Snowmen. A large party of servant and soldier types stood in the middle distance, while just ten meters away, five others—all dressed in heavily jeweled leggings—sat around a furcovered table. She recognized at least one of those: the greasy character she had met in the Summerpalace—Bre’en, was that his name? Even now that the witlings were awake, their captors regarded them impassively, as if the prisoners were insects on display. Beside the table stood the black hull of the ablation skiff that she and Ajão had so carefully stowed in the hold of Pelio’s yacht. And there, on the table, sat the maser, the machine pistols—even the machete from their survival kit! The witlings had been so sure that only a Guildsman or a high nobleman of Summer could rob the Keep that they had walked unknowingly into the hands of the real enemy.

The Bre’en creature stood up, his naked chest gleaming in the yellow sunlight. “Good, you are awake.” His face creased with the same easy grin he had displayed back in the Summerpalace. “Ionina, Adgao, I regret that we used trickery to bring you here to the pole. There is no storm on the Island Road. But don’t blame your men for not senging our deception; the road is indeed frozen over—we gave our icechipping crews a few hours’ vacation and the winter cold did the rest.

“Frankly, our lies were born of desperation. You were too well guarded and too misinformed for us to approach you directly. Yet, as evidence of our good intentions, you have the honor of being interviewed by the king of our land and his highest ministers.” Bre’en bowed toward the short and exceptionally fat Snowman who sat at the head of the table. That worthy raised his round chin a fraction of a degree to acknowledge the introduction. The guards behind the five stared impassively.

Before the Snowman could continue, Ajão interrupted. “How did you, how did you—”

“How did we render you senseless? We of the poles have our magics, too, Adgao, although they do not compare with what we have seen of yours. In certain places in the North, during the winter there, it becomes so cold that thin layers of a magical snow grow on the ice—a secret gift of nature to our kingdom. This enchanted snow disappears when warmed, yet if it is warmed in an enclosed space, then anyone living in that space must fall to sleep.”

Bull!

thought Leg-Wot, as she tore the superstitious wrappings from the Snowman’s statement. He must be talking about frozen CO

2

. There might just be places cold enough on Giri for the stuff to form.

“In due time we will revive your crew.” He waved at the transit pool behind him. Pelio’s yacht floated near the far end, the hull tilting at an unnatural angle against the pool’s wall. The boat’s hatches were sealed. “But for now they are better off asleep.”

Pelio shot to his feet. “You” (unknown word) “liar! You’ve killed my men.” His glare turned upon the Snowking. “How dare you allow such treachery, Tru’ud? Do treaties mean so little to you?”

King Tru‘ud started to sneer, then controlled himself and simply looked away from the prince. Bre’en was a good deal less cordial when he responded to the boy. “You are impertinent, Prince Pelio. No one has been murdered. We used the least force possible—and that only when it became clear that the Summerkingdom did not intend to share our visitors’ knowledge. If we

had

killed your crew, why would we spare you? With your suspicions unspoken wouldn’t it be easier to win over your two friends?”

The argument didn’t appeal to Pelio. “I don’t know why you didn’t finish me off with the others. But I

do

know you can never let us go. Only as long as you can tell my family that a ‘terrible accident’ destroyed my yacht will you have any chance of avoiding war with the Summerkingdom.”

Bre’en shrugged, and turned to the Novamerikans with an apologetic smile. “Anyway, we hope you will see the truth of what we say. At the Summerfest you claimed that you were somehow going to travel across the Great Ocean. We aren’t sure if you were bluffing or not, but we do know that King Shozheru gave you only a few days to prepare for the attempt, and that he had secret plans to betray you in case you seemed close to success. You will find my king more lenient. He is prepared to give you protection, time, and personal comfort … if you will share your magic with us.

“And we know that magic is powerful, perhaps more powerful than the Guild itself. We had men in the hills north of Bodgaru at the time of your capture. One saw the flying monster come to your aid, and others saw it burning down through the sky, hundreds of miles north of you; the creature was making better time than most road boats do in those latitudes. We believe that if you had not been completely ignorant of the Talent, you might have succeeded in fighting off the troops that Prefect Moragha sent against you.

“Since that time, several of your talismans have come into our possession, and these further strengthened our notion of your importance.” He gestured at the maser and other pieces of equipment that had been stolen from the Summerpalace.

“Yes,” interrupted Pelio, “just how did you get these things out of the Keep?”

“That, of course, is our secret,” said the Snowman. Then his egotism got the better of him and he grinned at Pelio. “But I can say that we did it even as you and Ionina looked on.”

How was that possible? When she saw Bre‘en and his men at the Keep, they had been empty-handed. The maser and the pistols were not large—none measured more than eighty by twenty centimeters—but you could hardly conceal them in your leggings.

Or could you

? Suddenly she remembered the strange, stiff-legged gait of Bre’en’s servants, and a ghastly thought occurred to her; what if those men were amputees? If they could fool the guards’ density sense … each stolen object could fit easily within the stubby outline of an Azhiri’s lower leg. Of course, the men would be crippled for the rest of their lives, but that might not bother the Snowking. It was obvious he played rough.