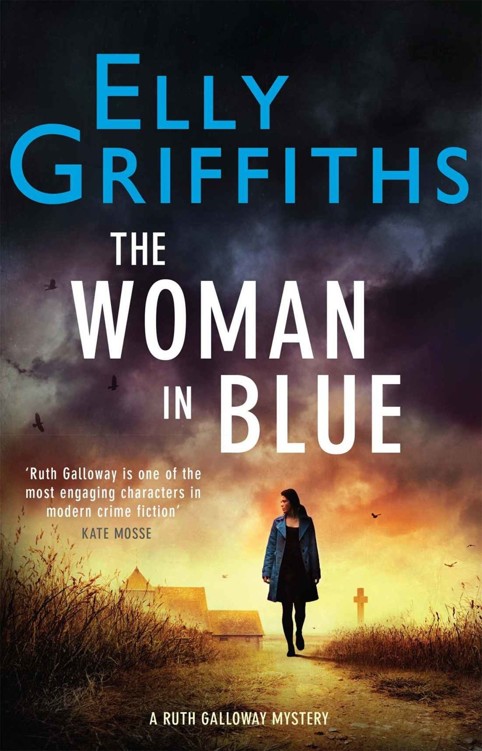

The Woman In Blue: The Dr Ruth Galloway Mysteries 8

Read The Woman In Blue: The Dr Ruth Galloway Mysteries 8 Online

Authors: Elly Griffiths

The Woman in Blue

About the Author

Elly Griffiths

was born in London and worked in publishing for many years. Her bestselling series of Ruth Galloway novels, featuring a forensic archaeologist, is set in Norfolk, and has been shortlisted three times for the Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year, and three times for the CWA Dagger in the Library. Her new series is based in 1950s’ Brighton. She lives near Brighton with her husband, an archaeologist, and their two children.

Also By

Also by Elly Griffiths

THE RUTH GALLOWAY SERIES

The Crossing Places

The Janus Stone

The House at Sea’s End

A Room Full of Bones

Dying Fall

The Outcast Dead

The Ghost Fields

THE STEPHENS AND MEPHISTO SERIES

The Zig Zag Girl

Smoke and Mirrors

Title

Copyright

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Quercus Editions Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK company

Copyright © 2016 Elly Griffiths

The moral right of Elly Griffiths to be identified as the

author of this work has been asserted in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording,

or any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

HB ISBN 978 1 78429 237 9

TPB ISBN

978 1 84866 335 0

EBOOK ISBN 978 1 78429 238 6

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses,

organizations, places and events are either the product of the

author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance

to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

You can find this and many other great books at

Dedication

For Giulia

Map

Epigraph

Weep, weep, O Walsingham,

Whose dayes are nights,

Blessings turned to blasphemies,

Holy deeds to despites.

Sinne is where Our Ladye sate,

Heaven turned is to helle;

Satan sitthe where our Lord did swaye,

Walsingham, O farewell!

Ballad of Walsingham, anonymous, sixteenth century

Contents

Prologue

19

th

February 2014

Cathbad and the cat look at each other. They have been drawing up the battle-lines all day and this is their Waterloo. The cat has the advantage: this is his home and he knows the terrain. But Cathbad has his druidical powers and what he believes is a modest gift with animals, a legacy from his Irish mother who used to talk to seagulls (and receive messages back). He has a companion animal himself, a bull-terrier called Thing, and has always enjoyed a psychic rapport with Ruth’s cat, Flint.

This cat, whose name is Chesterton, is a different proposition altogether. Whereas Flint is a large and lazy ginger Tom whose main ambition is to convince Ruth that he is starving at all times, Chesterton is a lithe and sinuous black creature, given to perching on top of cupboards and staring at Cathbad out of disconcertingly round, yellow eyes. This is Cathbad’s third day of house- and cat- sitting, and so far Chesterton has ignored all blandishments. He has even ignored the food that Cathbad carefully weighed out according to Justin’s instructions. He might be living on mice, but Chesterton does not look like an animal who is governed by his appetites. He’s an ascetic, if Cathbad ever saw one.

But Justin’s sternest admonition, written in capitals and underlined in red, was: DO NOT LET CHESTERTON OUT AT NIGHT. And now, here they are, at nine o’clock on a February evening with Chesterton staring at the door and Cathbad barring the way with his fiery sword. The biblical reference comes to hand because the house is part of an ancient pilgrimage site and is decorated with etchings from the Old Testament. Justin, a custodian of the site, is on a fact-finding trip to Knock, something Cathbad finds extremely funny. He has left the fifteenth-century cottage – and the accompanying cat – under Cathbad’s protection.

Chesterton meows once, commandingly.

‘I’m sorry,’ says Cathbad. ‘I can’t.’

Chesterton gives him a pitying look, jumps onto a cupboard and manages to slide out through a partially opened window. So that’s why he has been on hunger strike.

‘Chesterton!’ Cathbad lifts the heavy latch and opens the door. Cold air rushes in. ‘Chesterton! Come back!’

The cottage is attached to the church, with a passageway through it at ground-floor level forming a kind of lych-gate. Worshippers have to pass underneath the main bedroom in order to get to St Simeon’s. There’s even a handy recess in the wall of the passage so that pall-bearers can rest their coffins there. The back door of the cottage opens directly onto the churchyard. ‘But you won’t mind that,’ said Justin, ‘it’s right up your street.’ And it’s true that Cathbad does like burial grounds, and all places of communal worship but, even so, there’s something about St Simeon’s Cottage, Walsingham, that he doesn’t quite like. It’s not the presence of the cat, or the creaks and groans of the old house at night; it’s more a sort of sadness about the place, a feeling so oppressive that, during his first evening, Cathbad was compelled to call upon a circle of protection and to ring his partner Judy several times.

He’s not scared now, just worried about the cat. He walks along the church path, the frost crunching under his feet, calling the animal’s name.

And then he sees it. A tombstone near the far wall, glowing white in the moonlight, and a woman standing beside it. A woman in white robes and a flowing blue cloak. As Cathbad approaches, she looks at him, and her face, illuminated by something stronger than natural light, seems at once so beautiful and so sad that Cathbad crosses himself.

‘Can I help you?’ he calls. His voice echoes against stone and darkness. The woman smiles – such a sad, sweet smile – shakes her head and starts to walk away, moving very fast through the gravestones towards the far gate.

Cathbad goes to follow her, but is floored, neatly and completely, by Chesterton, who must have been lurking behind a yew tree for this very purpose.

Chapter 1

DCI Harry Nelson hears the news as he is driving to work. ‘Woman’s body found in a ditch outside Walsingham. SCU request attend.’ As he does a handbrake turn in the road, he is conscious of a range of conflicting emotions. He’s sorry that someone’s dead, of course he is, but he can’t help feeling something else, a slight frisson of excitement, and a relief that he’s been spared that morning’s meeting with Superintendent Gerald Whitcliffe and their discussion of the previous month’s targets. Nelson is in charge of the SCU, the Serious Crimes Unit, but the truth is that serious crime is often thin on the ground in King’s Lynn and the surrounding areas. That’s a good thing – Nelson acknowledges this as he puts on his siren and speeds through the morning traffic – but it does make for rather dull work. Not that Nelson hasn’t had his share of serious crime in his career – only a few months ago he was shot at and might have died if his sergeant hadn’t shot back – but there’s also a fair amount of petty theft, minor drugs stuff and people complaining because their stolen bicycle wasn’t featured on

Crimewatch

.

He calls his sergeants, Dave Clough and Tim Heathfield, and tells them to meet him at the scene. Though they both just say ‘Yes, boss’, he can hear the excitement in their voices too. If Sergeant Judy Johnson were there, she would remind them that they were dealing with a human tragedy, but Judy is on maternity leave and so the atmosphere in the station is rather testosterone heavy.

He sees the flashing lights as he turns the corner. The body was found on the Fakenham Road, about a mile outside Walsingham. It’s a narrow road with high hedges on both sides, made narrower by the two squad cars and the coroner’s van. As soon as Nelson steps out of his car he feels claustrophobic, something that often happens when he’s in the countryside. The high green walls of foliage make him feel as if he’s in the bottom of a well and the grey sky seems to be pushing down on top of him. Give him pavements and street lighting any day.

The local policemen stand aside for him. Chris Stephenson, the police pathologist, is in the ditch with the body. He looks up and grins at Nelson as if it’s the most charming meeting place in the world.

‘Well, if it isn’t Admiral Nelson himself!’

‘Hallo, Chris. What’s the situation?’

‘Woman, probably in her early to mid-twenties, looks like she’s been strangled. Rigor mortis has set in, but then it was a cold night. I’d say she’s been here about eight to ten hours.’

‘What’s she wearing?’ From Nelson’s vantage point it looks like fancy dress, a long white robe and some sort of blue cloak. For a moment he thinks of Cathbad, whose favourite attire is a druid’s cloak. ‘It’s both spiritual and practical,’ he’d once told Nelson.

‘Nightdress and dressing gown,’ says Stephenson. ‘Not exactly the thing for a February night, eh?’

‘Has she got slippers on?’ Nelson can see a glimpse of bare leg, ending in something white.

‘Yes, the kind you get free in spas and the like,’ says Stephenson, who probably knows a lot about such places. ‘Again, not exactly the thing for tramping over the fields.’

‘If her slippers are still on, she must have been placed in the ditch and not thrown.’

‘You’re right, chief. I’d say the body was placed here with some care.’ Stephenson holds out an object in a plastic bag. ‘This was on her chest.’

‘What is it? A necklace?’

Stephenson laughs. ‘I thought you were a left-footer, Admiral. It’s a rosary.’

A rosary. Nelson’s mother has a wooden rosary from Lourdes and she prays a decade every night. Nelson’s sisters, Grainne and Maeve, were given rosaries for their First Holy Communions. Nelson didn’t get one because he was a boy.

‘Bag it,’ he says, although the rosary is already sealed in a plastic evidence bag. ‘It’s important evidence.’

‘If you say so, chief.’

Nelson straightens up. He has heard a car approaching and guesses that it’s Clough and Tim. Besides, he’s had enough of Chris Stephenson and his breezy good humour.

His sergeants come towards him. Both are tall and dark and have been described (though not by Nelson) as handsome, but there the resemblance ends. Clough is white and Tim is black, but there’s much more to it than that. Clough is heavily built, wearing jeans and skiing jacket. He’s looking around with something like excitement and there’s a half-eaten bagel in his hand. Tim is taller and slimmer, he’s wearing a long dark coat and knotted scarf and could be a politician visiting a factory. His face gives nothing away.

Nelson briefs them quickly. He calls over the local officer, who explains that the body was found by an early morning dog-walker. ‘Her little dog actually got into the ditch and was . . . well . . . shaking the deceased.’

‘If she’s in nightclothes,’ says Tim, ‘she could be a patient at the Sanctuary.’

The same thought has occurred to Nelson. It was the waffle-patterned slippers that first gave him the idea. The Sanctuary is a private hospital specialising in drug rehabilitation. Because a lot of the patients are famous (though not to Nelson), the place exists in an atmosphere of high walls, secrecy and rumours of drug-fuelled orgies. It is quite near here, about a mile across the fields.

‘Good thinking,’ he says. ‘You and Cloughie can go over there in a minute and ask if any patients are missing.’

‘Foxy O’Hara’s meant to be there at the moment,’ says Clough, swallowing the last of his bagel.

‘Who?’

‘You must have heard of her. She was on

I’m a Celebrity

before Christmas.’

‘You’re jabbering, Cloughie.’ Nelson turns to Chris Stephenson, who has emerged from the ditch and is taking off his coveralls. ‘Anything else for us, Chris? No handy nametapes on the dressing gown?’

‘No, but it’s a good one. Pricy. From John Lewis.’

‘Costs a bit to stay in the Sanctuary,’ says Nelson. ‘I think that’s our best bet.’

‘Excuse me, sir.’ It’s one of the local policemen, nervous and respectful. ‘But there’s a man asking to see you. Looks a bit of a nutter, but he says he knows you.’

‘Cathbad,’ says Clough, without looking round.

Clough is right. Nelson sees Cathbad standing beyond the police tape, wearing his trademark cloak. How strange, and slightly unsettling, that Nelson was thinking about him only a few moments before. He strides over.

‘Cathbad. What are you doing here?’

‘I’m house-sitting in Walsingham.’

‘What about Judy? Have you left her alone with a newborn baby?’

‘Miranda’s ten weeks old and she’s an old soul. No, Judy’s taken the children to visit her parents.’

‘That doesn’t explain why you’re here, at a crime scene.’

‘The woman you’ve found,’ says Cathbad. ‘Was she wearing a blue cloak?’

Nelson takes a step back. ‘Who says we’ve found a woman?’

He half-expects Cathbad to say something about spiritual energies and cosmic vibrations, but instead he says, ‘I heard the milkman talking about it. Useful people, milkmen. They’re up and about early, they notice things.’

‘And what did you mean about a cloak? I’m sure the bloody milkman didn’t see that.’

Cathbad exhales. ‘So it is her.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘The cottage where I’m staying, it overlooks the graveyard.’ That figures, thinks Nelson. ‘Well, last night, I saw a woman standing there, a woman wearing a white robe and a blue cloak.’

‘What time was that?’

‘About nine.’

Nelson lifts the tape. ‘You’d better come through.’

The scene-of-the-crime team have arrived. In their paper suits and masks they look like aliens taking over a sleepy Norfolk village. As Nelson and Cathbad watch, the dead woman’s body is slowly winched out of the ditch. The corpse is covered with a sheet, but as the stretcher passes them they both see a length of muddy blue material hanging down. Cathbad crosses himself and Nelson has to stop himself following suit.

‘Any idea who she was?’ asks Cathbad.

‘She was in nightclothes,’ said Nelson. ‘Your “cloak” was a dressing gown. I’m sending Clough and Heathfield to the Sanctuary.’

‘Do you think she was a patient there?’

‘It’s a line of enquiry.’

The aliens have now erected a tent-like structure over the ditch. The atmosphere has somehow stopped being that of an emergency and has become calm and purposeful.

‘Look, Cathbad,’ says Nelson. ‘I’m going to brief the boys and finish up here. Then I’ll come and talk to you about what you saw last night. Where’s this place you’re staying?’

‘St Simeon’s Cottage. Next to the church.’

‘I won’t be long.’

‘Time,’ says Cathbad grandly, ‘is of no consequence.’ But he is talking to the empty air.

*

Ruth Galloway doesn’t hear about the body in the ditch until she’s at work. She did listen to the radio in the car, but what with the hassle of getting her five-year-old daughter, Kate, to school in time, it all became rather a blur. ‘Have you got your book bag?’ . . . Here’s Gary with the sports news . . . ‘Can you see a parking space?’ . . . Thought for the Day with the Revd . . . ‘Quick, there’s Mrs Mannion waiting for you. Love you. See you later.’ . . . Icy winds, particularly on the east coast . . . If the dead woman did make it on to the

Today

programme, Ruth missed it altogether. It wasn’t until she was at her desk, trying to catch up on emails before her first tutorial, that her head of department, Phil Trent, wandered – uninvited – into her office and asked if she’d heard ‘the latest drama’.

‘No. What?’

‘A woman found dead in a ditch out Walsingham way. It was on

Look East

.’

‘I must have missed it.’

‘I thought you had a hotline to the boys in blue.’

Phil is jealous of Ruth’s role as a special advisor to the police and sometimes she likes to tease him, dropping hints of high-level meetings and top-secret memos, but this morning she doesn’t have the energy.

‘I doubt it will have anything to do with me. Not unless there’s an Iron Age skeleton in the ditch as well.’

‘I suppose not.’

Ruth turns back to her screen, and though Phil hovers in the doorway for a few minutes, eventually he drifts away, leaving her to concentrate on her emails. They are the usual collection of advertisements from academic publishers, departmental memos and requests from her students for extra time to finish their essays. Ruth deletes the first and the second and is settling down to answer the third when she sees a new category of email. The subject is ‘Long time no see’. This is either intriguing or worrying, depending on your mood. Ruth is probably fifty–fifty on that. She clicks it open.

Hi, Ruth,

Do you remember me, Hilary Smithson, from Southampton? Where have the years gone? I understand that you’re in Norfolk, doing very well for yourself. I’m coming to Norfolk next week, for a conference in Walsingham, and I wondered if we could meet up? I’d like to ask your advice on a rather tricky matter. And I’d love to see you of course. Looking forward to hearing from you.

All best,

Hilary

Ruth stares at the screen. It’s the second time that Walsingham has been mentioned that morning and, as Nelson always says, there’s no such thing as coincidence.