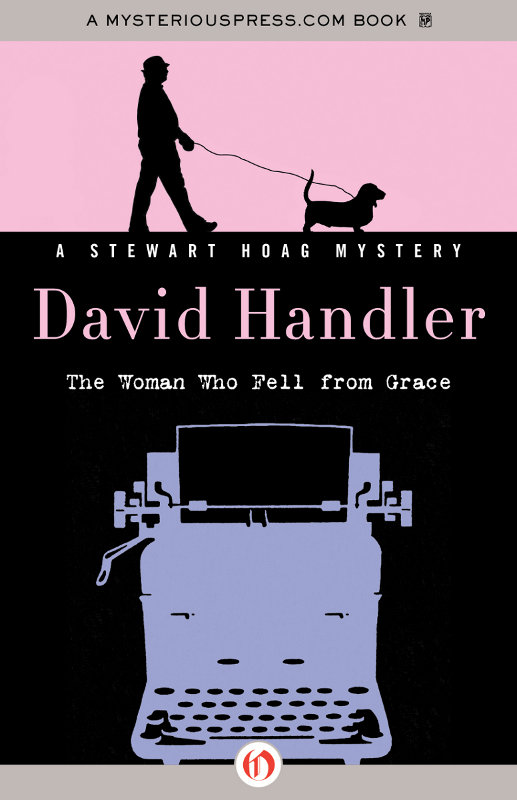

The Woman Who Fell From Grace

A Stewart Hoag Mystery

David Handler

A MysteriousPress.com

Open Road Integrated Media

Ebook

For Stella

who has been nice enough to

stay behind

It’s being hailed as the ultimate American novel, and maybe it is. It’s huge, loud, sentimental, and its pants are on fire. It’s also a rollicking good time. I devoured it in greedy bites and would happily come back for seconds.

—from Dorothy Parkers review of

Oh, Shenandoah

in the Sunday

New York Times

, June 2, 1940

Preview:

The Boy Who Never Grew Up

I

WAS STANDING IN

the lobby of the Algonquin Hotel seeing double. Two utterly distinguished, utterly identical elderly gentlemen sat there before me sipping on martinis at one of the small, round lounge tables. They had the same handsome, patrician face — eyes blue, brows arched, nose long and rather sharp, chin cleft, hair silver and wavy. They wore the same double-breasted navy blazer, white cotton broadcloth shirt, yellow-and-burgundy-striped silk tie. They looked up at me at the same time. They smiled at me at the same time. Same smile. Same teeth. White.

I had to blink several times to make sure I wasn’t having an acid flashback from the summer of ’70, the one I can’t remember too much about, except that I wanted to move to Oregon and raise peaches. I even shot a glance down at Lulu, my basset hound, who was looking uncommonly pert that season in the beret Merilee had bought her in Paris. Lulu was blinking, too.

“Frederick, Mr. Hoag,” said one, as I dumbly shook his long, slender hand.

“Edward, Mr. Hoag,” said the other, as I shook his. “Won’t you please join us, sir?” they said in perfect harmony.

Harmony because their voices were different. Each spoke with the gentle, courtly accent of the Southern aristocrat. But while Frederick’s voice was husky, Edward’s was softer, higher pitched. A small distinction, but I had to grab on to something, anything, to keep from hooting. I joined them. Lulu turned around three times at my feet and curled up with a contented grunt. She likes the Algonquin. Always has.

It was after five and the place was filling up with the pasty-faced English tourists and assorted New York literary fossils and bottom feeders who usually hang around there. Peter Ustinov was giving a radio reporter an interview on the sofa next to us, and a whole new meaning to the words

couch potato

. Rog Angell was busy demonstrating the hitch in the Straw Man’s swing to two other owlish

New Yorker

editors. Pretty much everybody else in the hotel was staring at Eddie and Freddie, who might have been retired diplomats or rear admirals or a new set of Doublemint Twins for the Depend-undergarment set, but who were actually the Glaze brothers of Staunton, Virginia, the exceptionally shrewd keepers of the

Oh

,

Shenandoah

flame. It was the Glaze brothers who had just engineered the record-shattering $6.2-million auction for the most eagerly awaited literary sequel of all time, the sequel to

Oh

,

Shenandoah

, the epic romance novel of the American Revolution penned in 1940 by their mother, Alma Glaze.

Oh

,

Shenandoah

wasn’t the greatest novel in the history of publishing, but it certainly was the most popular. More than 30 million readers in twenty-seven different languages had gobbled up the thousand-page saga through the years. Ten times that many had seen the Oscar-winning movie, which in the opinion of most critics ranked as the greatest Hollywood blockbuster of all time, greater than

Gone With the Wind

, than

Citizen Kane

, than

Yes

,

Georgio

. For decades, fans had been clamoring for a sequel. Now they were going to get one.

“So glad you could make it, Mr. Hoag,” Frederick rasped as he rang the bell on our table for our waiter.

“My pleasure. And make it Hoagy.”

“As in Carmichael?” asked Edward softly.

“As in the cheese steak.”

“Would that be the one they serve in Buffalo?” Frederick inquired.

“Philadelphia. It’s chicken wings they do in Buffalo.”

“And I’m sure they do them exceedingly well,” said Edward graciously.

Our waiter, Frank, hurried over and said how nice it was to see me again. The Glaze brothers ordered another round of martinis. I tagged along, heavy on the olives. Lulu had her usual. After Frank went off, Edward leaned over and scratched her belly roughly, as if she were a hunting dog. She’s more the champagne-and-caviar type. She snuffled in protest.

He immediately made a face. “My goodness. Her breath is somewhat … ”

“She has rather strange eating habits.”

Frank returned with our drinks and a plate of pickled herring and raw onion for Lulu. She attacked it at once. The brothers watched her. They sipped their drinks. They glanced at each other. I watched them, beginning to detect the subtle differences. Frederick had a more relaxed set to his jaw and shoulders, an easier manner. Edward appeared more formal and reserved. The shy one.

It was Frederick who began. “Exactly how much do you know about this project of ours, Hoagy?”

“Very little. I’ve been away.”

He leaned forward eagerly. “With Merilee Nash?”

“Frederick, please,” scolded Edward. “You’re being nosy.”

“It’s okay,” I assured him. “I’m used to being a public laughingstock. It’s kind of a nice feeling, after a while.”

“I shall bring you up to date, if I might,” said Frederick. “As you may know, our mother, in her last will and testament, specified that no sequel to

Oh

,

Shenandoah

would be authorized until some fifty years after her death, which is —”

“Which is to say

now

,” interjected Edward.

Frederick shot him a cool glance, then turned back to me. “Sometime before her death, Mother had in fact outlined the plot for a second volume, which was —”

“Which was to be called

Sweet Land of Liberty

,” Edward broke in.

Frederick shot him another cool look. He clearly didn’t like it when Edward interrupted him. Something told me that Eddie had been doing it for sixty years. “

Which

,” Frederick went on, “she then tucked away in the safe in the library of Shenandoah, our family’s estate, where it has remained, sealed, until —”

“Until a few weeks ago,” Edward said. “When it was, at long last, opened.”

Frederick calmly pulled a slim gold cigarette case from the inside pocket of his blazer, removed a cigarette, and lit it with a gold lighter. He politely blew the smoke away from me. He blew it directly toward Edward, who scowled and waved it away, irritably.

“The safe’s opening,” Frederick continued, “took place live on national television. That Geraldo Rivera person. Perhaps Mr. Rivera is a friend of yours … ?”

I popped one of my olives in my mouth. “Not even maybe.”

“Horrible little man,” sniffed Edward.

“Garish display,” agreed Frederick. “Mave’s idea, naturally.”

“Naturally,” said Edward.

Mave was their younger sister, Mavis Glaze, the socialite who wasn’t quite so famous as their mother but who was damned close. Ever since the late seventies, when the PBS affiliate in Washington, D.C., asked her to host a little half-hour, weekly show on social graces called

Uncommon Courtesy

. Something about the stern, matronly way she said “Courtesy is most decidedly

not

common” had tickled Johnny Carson’s funny bone. He began to make her the butt of his nightly monologue jokes, and then a frequent guest on

The Tonight Show

, and before long her show had gone national and Mavis Glaze had become the Jack Lalanne of manners with a chain of more than seven hundred etiquette schools. To get Mavis Glazed was to emerge civil and poised, the perfect hostess, the perfect guest. “Civilization,” declared Mavis over and over again in her endless TV commercials, “starts here.” She ran her empire from Shenandoah, the historic 5,000-acre estate that had been in the Glaze family since the days when Virginia was the jewel of the colonies. Shenandoah was where Alma Glaze’s epic had been set. The movie had been filmed entirely on location there. Part of the time now it was open to the public, and the public came by the busload to see it. They felt a special kind of love for the place. Shenandoah was America’s ancestral home. It was even more popular with tourists than Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s home, situated across the Shenandoah Valley outside of Charlottesville. Jefferson was only our nation’s most brilliant president. He never won an Oscar.

“Given Mave’s own prominence,” Frederick went on, “we all felt that she —”

“

We

being my brother and I,” Edward broke in, “as well as the publisher and Mave … ”

“That Mave should author the sequel.” Frederick casually brushed some cigarette ash from the sleeve of his blazer onto the sleeve of Edward’s. Edward reddened and flicked it onto the floor. “It seemed only natural,” Frederick concluded.

I nodded, wondering how long it would be before one of them had the other down on the carpet in a headlock, and which one I’d root for.

“The understanding,” explained Edward, “was that we find a professional novelist to do the actual writing. Someone gifted enough to meet Mother’s high literary standards, yet discreet enough not to divulge their association with the project.”

“Or the contents of Mother’s outline,” Frederick added. “Just exactly what happens in

Sweet Land of Liberty

is a well-kept secret, Hoagy. We’ve planned it that way to heighten reader anticipation. The tabloids would happily pay one hundred thousand dollars to steal our thunder.”

I nodded some more. It’s something I’m pretty good at.

“We all felt a novelist successful in the romance field would be most appropriate,” said Edward. “The publisher came up with a list of several.” He rattled them off. Two were million-plus sellers of historical bodice-rippers in their own right — Antonia Raven and Serendipity Vale, whose real name was Norman Pincus.

“Unfortunately,” lamented Frederick, “none of them has worked out.”

“How many have you gone through?” I asked. You can only nod for so long.

“Five of them left the project after one day,” replied Edward. “Amply compensated for their time, of course. To assure their silence.”

“Three more didn’t make it to the end of the first day,” added Frederick “Pretty surprising that any red-blooded writer would walk away,” I said, “considering how much money is involved.”

“They didn’t walk, sir,” said Edward. “They ran.”

“Mavis,” explained Frederick, choosing his words carefully, “is, well,

Mavis

. She’s … She can be, perhaps, a bit … high-strung. Demanding. Magisterial … ”

“She makes Nancy Reagan look like Little Red Riding Hood,” Edward blurted out.

“A prize bitch,” acknowledged Frederick. “But she’s our baby sister and we love her.”

Edward nodded emphatically. At least they agreed on that. “Sounds like what you need,” I suggested, “is someone who’s used to being screamed at. Why don’t you ask around up at Yankee Stadium?”

“What we need,” said Edward, “is someone who can retain the flavor and spirit of

Oh

,

Shenandoah

. Otherwise, Mother’s fans will be terribly disappointed. Unfortunately, Mave has, well, some ideas of her own. Ideas that are nowhere indicated in any of Mother’s notes, though she insists they are indeed Mother’s very own.” He glanced uneasily over at Frederick, colored slightly, and lowered his voice. “Ideas she says Mother has personally communicated to her. While she sleeps. In her dreams.”

I tugged at my ear. “What kind of ideas are we talking about?”

“Queer ones,” Edward replied gravely. “Very, very queer.”

“According to the terms of our contract with the publisher,” said Frederick, “the estate has final say on the contents of the manuscript. We insisted upon it. If Mavis gets her way, Hoagy, and she always does, I have no doubt that the publication of

Sweet Land of Liberty

will rank as one of the greatest embarrassments in the history of American publishing. Not to mention a major financial disaster.”

“You’re her brothers,” I said. “Won’t she listen to you?”

“Mavis doesn’t have to listen to us if she doesn’t choose to,” replied Edward. “And she generally doesn’t choose to. You see, Hoagy, Mother believed in a system of matriarchy. We three children took her family name, Glaze, not father’s, which was Blackwell. And when she died, she left Shenandoah and the entirety of her fortune to Mave and Mave alone. Frederick and I merely serve her in an advisory capacity. I happen to practice law. Frederick is an investment counselor. Protecting the financial and legal interests of Shenandoah and Mavis does occupy much of our time, and Mave does pay us quite generously for it. But it is she who has final say in all estate matters.”